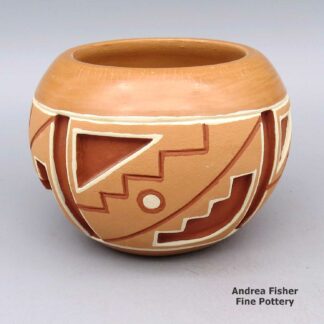

| Dimensions | 11.75 × 11.75 × 4.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, rubbing on bottom |

| Date Born | 2002 |

| Signature | Ambrose Atencio Kewa |

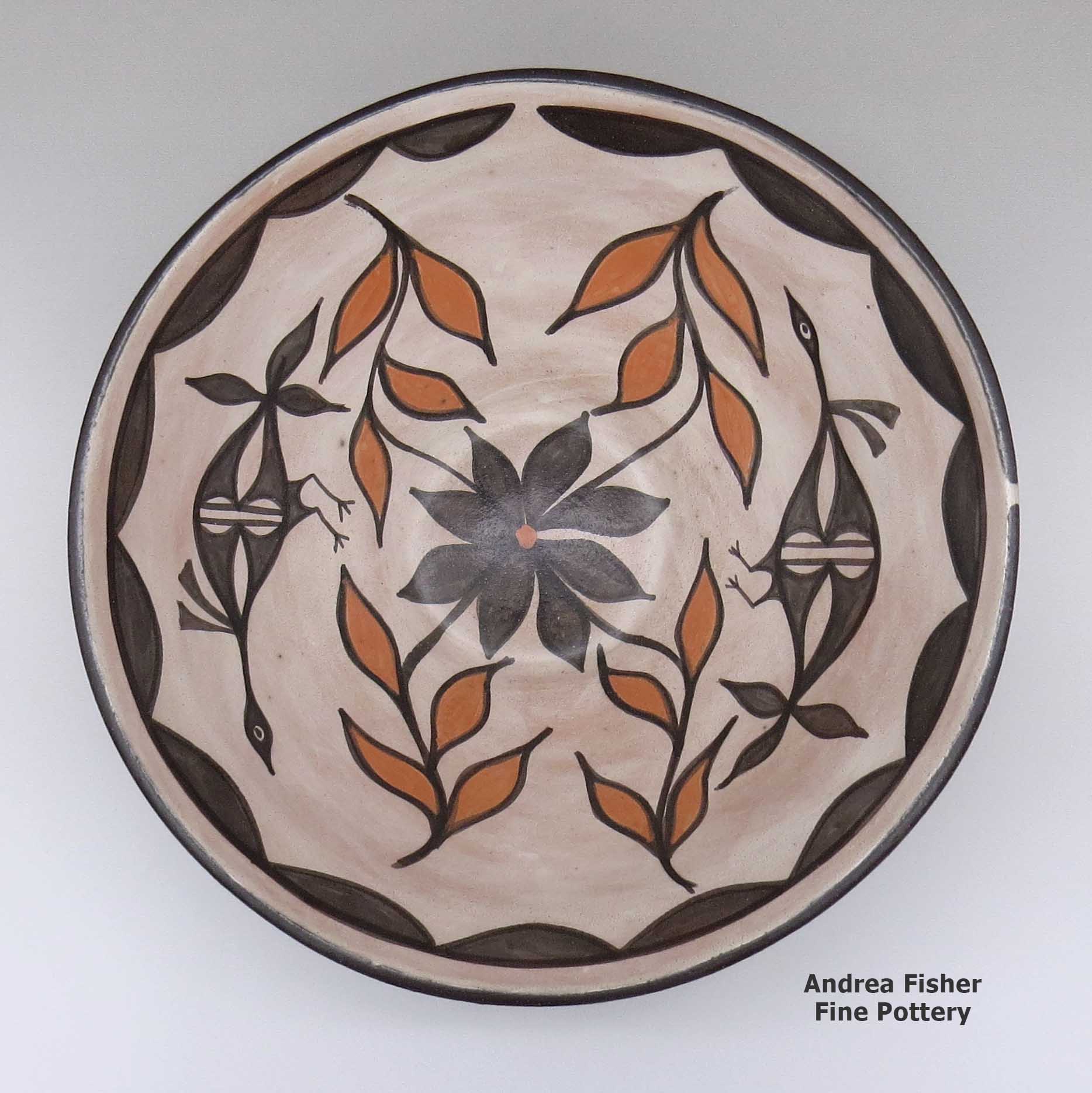

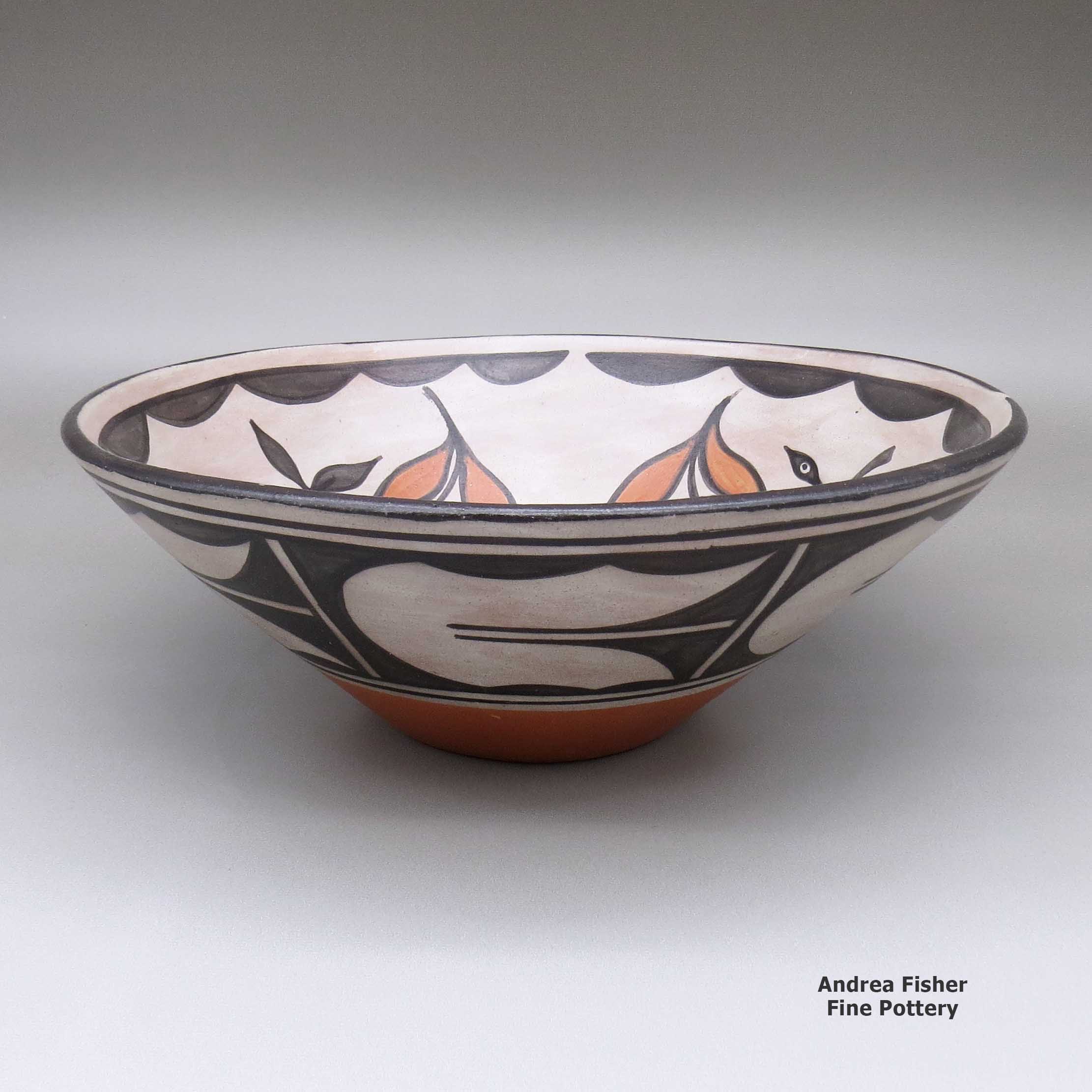

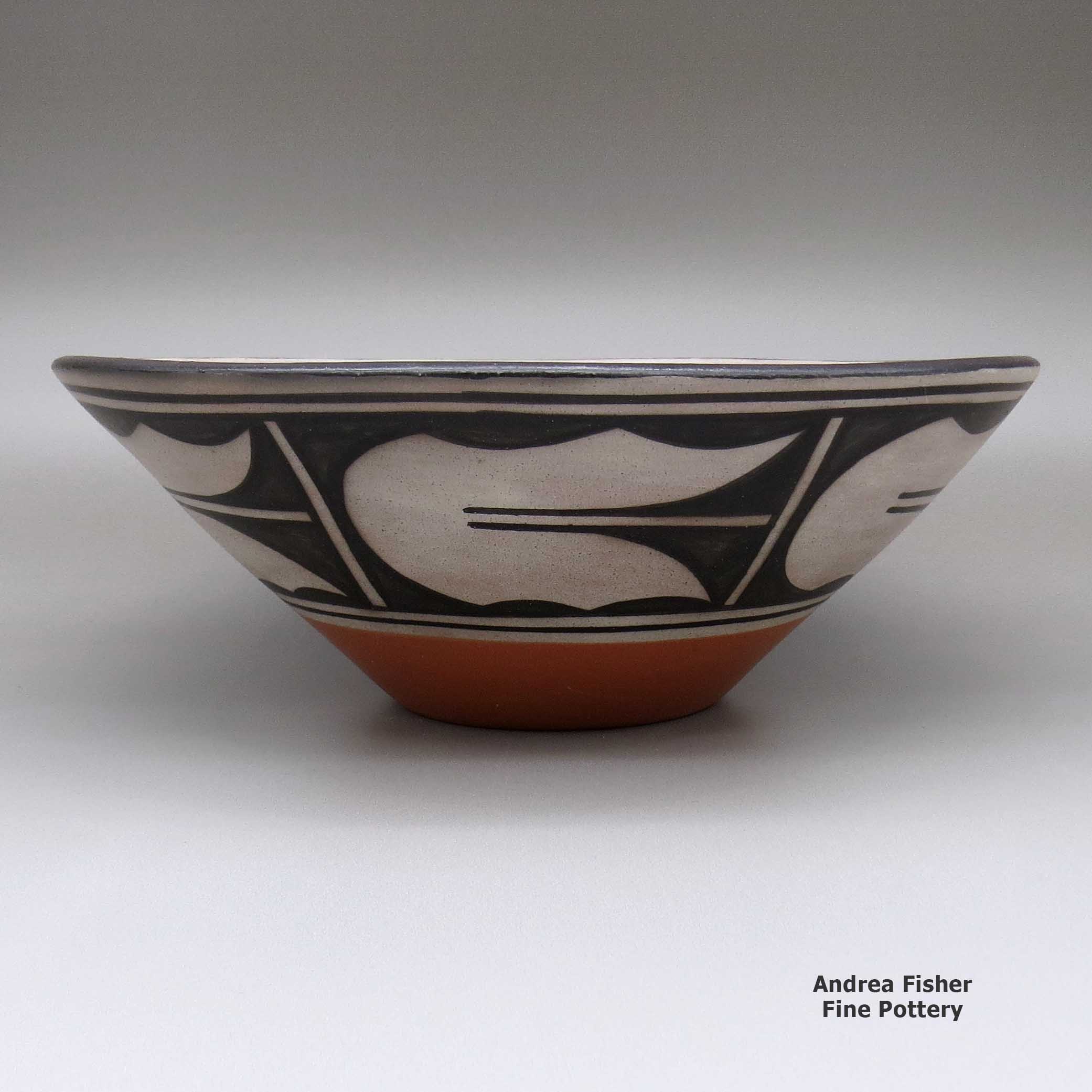

Ambrose Atencio, mgsd3c010, Bowl with a traditional Santo Domingo design

$795.00

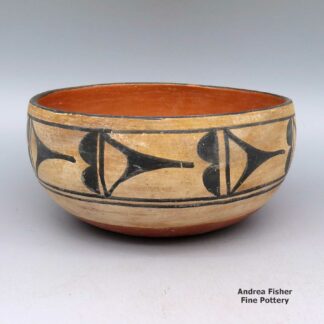

A polychrome bowl decorated with a traditional Santo Domingo bird, flower and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Atencio, Ambrose

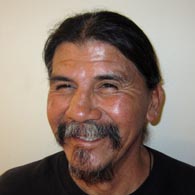

Ambrose Atencio was born to Joseph Ray Atencio and Juanita Atencio of Santo Domingo Pueblo in June, 1963. He told us he learned the traditional method of making pottery from his cousin, Robert Tenorio (and his family), starting around the time Ambrose was 13 years old. The years since then Ambrose has spent perfecting his technique. His progression is reflected in the perfect shape of his pots and in his exquisite execution of the traditional Santo Domingo designs that he chooses to use.

Ambrose Atencio was born to Joseph Ray Atencio and Juanita Atencio of Santo Domingo Pueblo in June, 1963. He told us he learned the traditional method of making pottery from his cousin, Robert Tenorio (and his family), starting around the time Ambrose was 13 years old. The years since then Ambrose has spent perfecting his technique. His progression is reflected in the perfect shape of his pots and in his exquisite execution of the traditional Santo Domingo designs that he chooses to use.He collects the basic materials to make his pottery on the lands of Santo Domingo Pueblo. When his pieces are finished and ready, Ambrose ground fires his work using cottonwood bark, like his grandmother, Crucita Tortalita (Robert Tenorio's maternal aunt), used to do. He's also taught his son Elroy to work with clay in the traditional way.

Ambrose has earned multiple awards at venues such as the Indian Arts Northwest Market in Portland, Oregon, the Fountain Hills Indian Market in Fountain Hills, Arizona, the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show in Espanola, New Mexico, the Dallas Indian Arts and Crafts Fair in Dallas, Texas, the Santa Fe Indian Market (where he's taken home ribbons for Best of Class, Best of Category and others), and the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market in Phoenix (where he's earned several ribbons).

Ambrose tells us his favorite shapes to make are storage jars and large dough bowls. He also really enjoys decorating them with traditional Santo Domingo birds, plants, animals and geometric designs. Like many Native American traditional potters, he says his inspiration comes from above, through the clay.

When he's not busy making new pots Ambrose says he enjoys hiking. On special occasions he enjoys music concerts, a favorite one having been a Fleetwood Mac concert on his birthday.

He signs his work: "Ambrose Atencio KEWA" and adds the date the pot was created.

Some of the Awards Ambrose has earned

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Class. II - Pottery, Div. E - Traditional pottery, jars, including wedding jars, Cat. 1204 - Jars, Santo Domingo or Cochiti, Third Place;

- Div. F - Traditional pottery, painted designs on matte or semi-matte surface, all forms except jars, Cat. 1302 - Other bowl forms, Second Place - 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Class. II - Pottery, Div. E - Traditional pottery jars, Cat. 1204 - Jars, Santo Domingo or Cochiti, First & Second Place

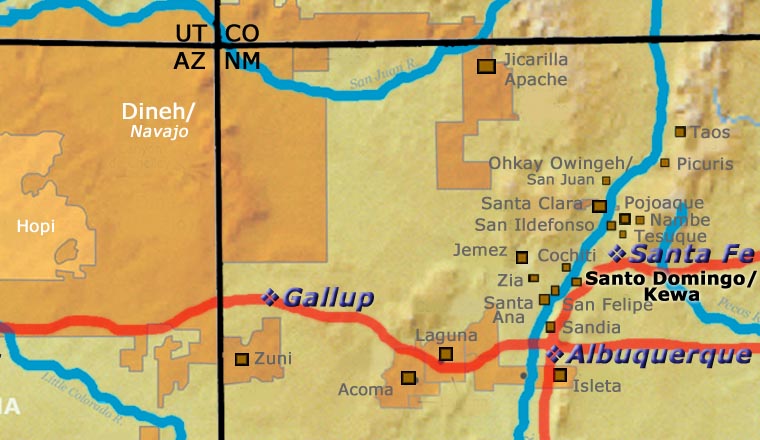

A Short History of Santo Domingo Pueblo

Santo Domingo Pueblo is located on the east bank of the Rio Grande about half-way between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Historically, the people of Santo Domingo were among the most active of Pueblo traders. The pueblo also has a reputation of being ultra traditional, probably due, at least in part, to the longevity of the pueblo's pottery styles. Some of today's popular designs have changed very little since the 1700's.

In pre-Columbian times, traders from Santo Domingo were trading turquoise (from mines in the Cerrillos Hills) and hand-made heishe beads as far away as central Mexico. Many artisans in the pueblo still work in the old ways and produce wonderful silver and turquoise jewelry and heishe decorations.

Like the people of nearby San Felipe and Cochiti, the people of Santo Domingo speak Keres and trace their ancestry back to villages established in the Pajarito Plateau area in the 1400s. Like the other Rio Grande pueblos, Santo Domingo rose up against the Spanish oppressors in 1680, following Alonzo Catiti as he led the Keres-speaking pueblos and worked with Popé (of San Juan Pueblo) to stop the Spanish atrocities. However, when Spanish Governor Antonio Otermin returned to the area in 1681, he found Santo Domingo deserted and ordered it burned. The pueblo residents had fled to a nearby mountain stronghold and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to Nuevo Mexico in 1692, he attacked that mountain fortress and burned it, too. Catiti died in that battle and Keres opposition to the Spanish crumbled with his death. The survivors of that battle fled, some to Acoma, some to fledgling Laguna, some to the Hopi mesas. Over time most of them returned to Santo Domingo.

In the late 1690s, Santo Domingo accepted an influx of refugees from the Galisteo Basin area as they fled drought and the near-constant attacks of Apache, Comanche, Ute and Navajo raiders in that area.

Today's main Santo Domingo village was founded about 1886.

In 1598 Santo Domingo was the site of the first gathering of 38 pueblo governors by Don Juan de Oñaté. He attempted to force them to swear allegiance to the crown of Spain. Today, the All Indian Pueblo Council (consisting of the nineteen remaining pueblo's governors and an executive staff) gathers at Santo Domingo for their first meeting every year, to continue what is now the oldest annual political gathering in America. During the time of the Spanish occupation, Santo Domingo served as the headquarters of the Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico and religious trials were held there during the Spanish Inquisition.

Today, the people of Santo Domingo number around 4,500 with about two-thirds of them living on the reservation.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Traditional Santo Domingo Design

Santo Domingo is considered a very conservative pueblo, especially when it comes to their religion. Their religion affects every aspect of the people's lives at Santo Domingo. Due to what has happened to them since Coronado and his men first arrived, they have become very secretive in regards to every aspect of their religious practices.

For example, artists are not allowed to depict human forms, especially on products meant for sale to outsiders. That restricts the artist's palette to images of birds, flowers, fish and various geometric patterns symbolizing water, forest, clouds, rain and lightning bolts. There is also a tradition at Santo Domingo of painting their pots completely in the negative using black and red pigments, rather than just painting in black and red on their usual "white" background slip.

Back in the 1920s, Kenneth Chapman, from the Museum of New Mexico, became worried that the Santo Domingo pottery tradition was dying. So he went there and, sitting among the potters, he copied the designs each were painting on their pots and made a book of those. Thomas Tenorio has told us that book is where he got many of his designs from.

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

Tenorio Family Tree - Santo Domingo Pueblo/Kewa

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Clemente & Nescita Calabaza (maternal side) & Andrea Ortiz (paternal side)

- Juanita Calabaza Tenorio (1922-1982) & Andres Tenorio

- Luciano Coriz & Marie Edna Coriz (1946-)(Jemez)

- Angel Bailon (1968-) & Ralph Bailon

- Paulita Pacheco (1943-2008) & Gilbert Pacheco (1940-2010)

- William Andrew Pacheco (1975-)

- Rose Pacheco (1968-) & Billy Veale (Navajo)

- Robert Tenorio (1950-)

Among Robert's students:

- Arthur Coriz (1948-1999) & Hilda Coriz (1949-2007)

- Ione Coriz (1973-)

- Warren Coriz (1966-2011)

- Luciano Coriz & Marie Edna Coriz (1946-)(Jemez)

-

Gilbert Pacheco's sisters who became potters:

- Laurencita Calabaza (c.1940s-)

- Santana Calabaza (c.1960s-)

- Trinidad Pacheco (c.1940s-)

- Vivian Sanchez (c.1940s-)

- Laurencita Calabaza (c.1940s-)