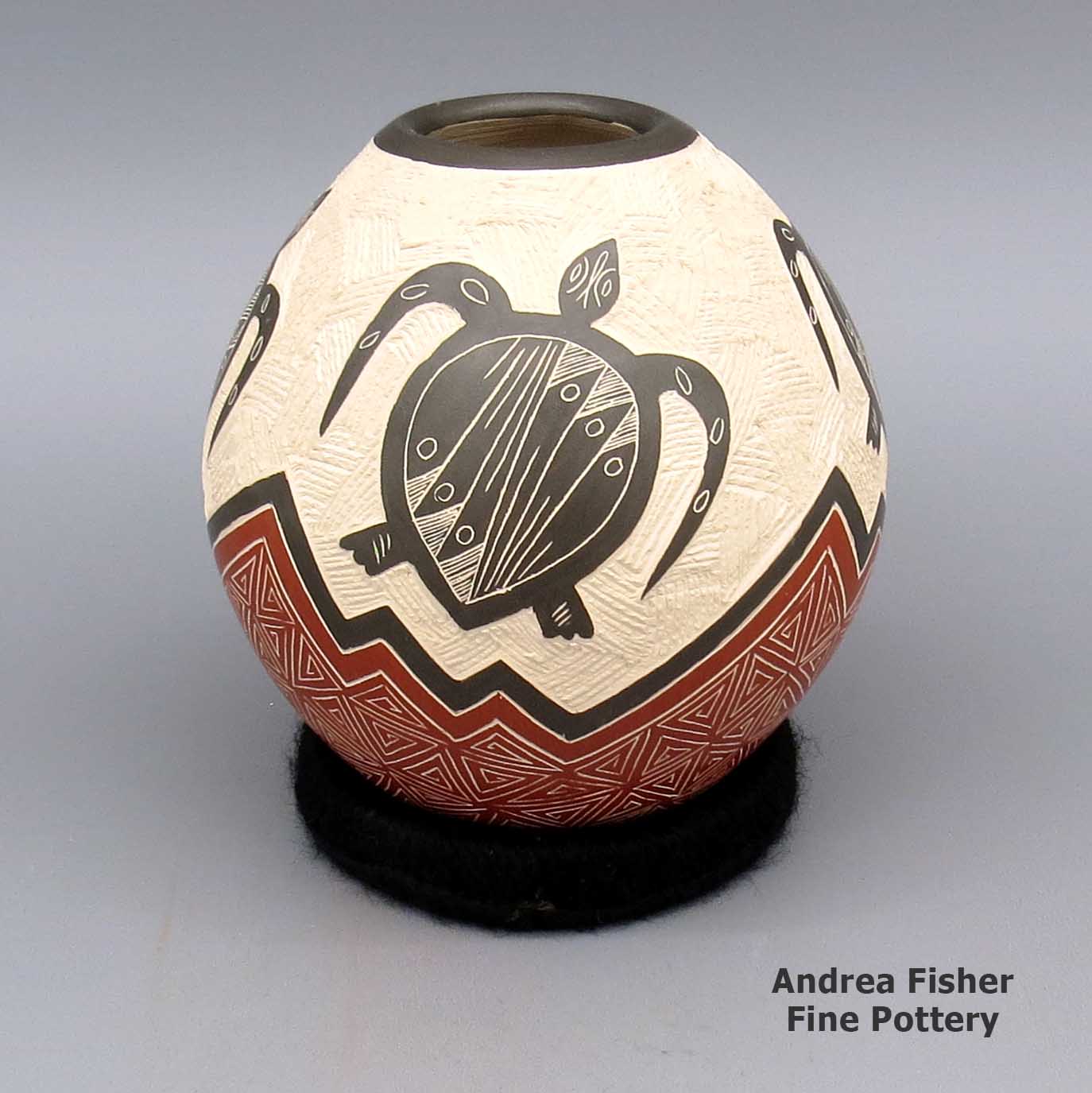

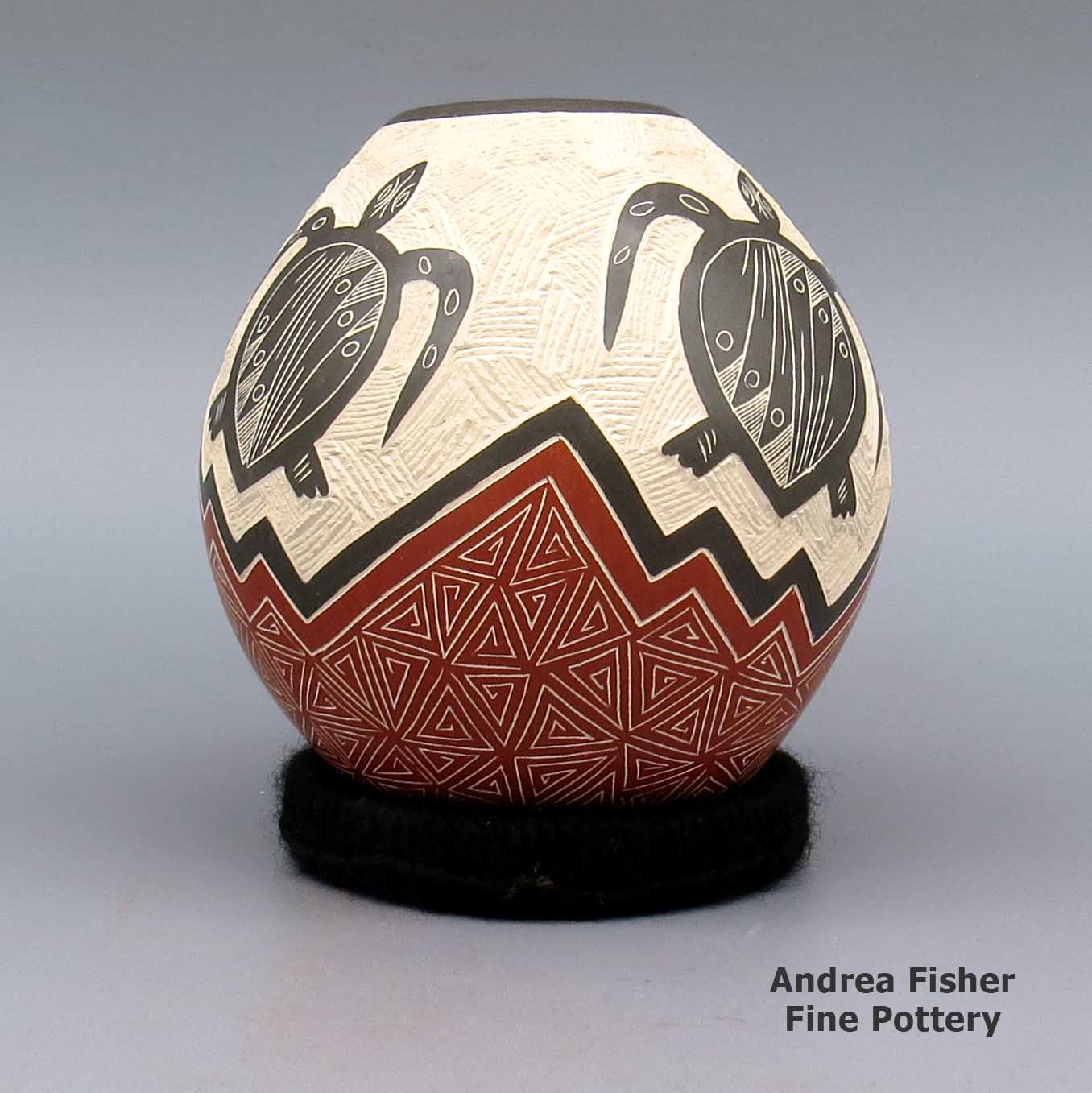

| Dimensions | 4.25 × 4.25 × 4.5 in |

|---|---|

| Measurement | Measurement includes stand |

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2022 |

| Signature | Octavio Silveira |

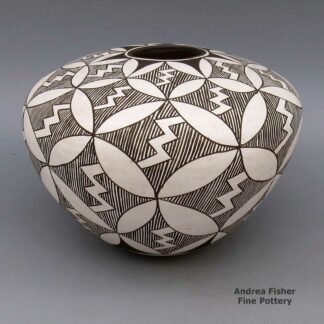

Octavio Silveira, zzcg2f334m3: Polychrome jar with sea turtle and geometric design

$150.00

A polychrome jar decorated with a sgraffito-and-painted sea turtle and geometric design

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

Silveira, Octavio

Octavio has developed a style of polychrome jar decorated with painted and sgraffito birds or bumblebees or dragonflies or butterflies bordered with bands of geometric designs that seems to be working well for him.

About Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes

Mata Ortiz is a small settlement inside the bounds of the Casas Grandes municipality, very near the site of Paquimé. The fortunes of the town have gone up and down over the years with a real economic slump happening after the local railroad repair yard was relocated to Nuevo Casas Grandes in the early 1960s. It was a village with a past and little future.

A problem around the ancient sites has been the looting of ancient pottery. From the 1950s on, someone could dig up an old pot, clean it up a bit and sell it to an American dealer (and those were everywhere) for more money than they'd make in a month with a regular job. And there's always been a shortage of regular jobs.

Many of the earliest potters in Mata Ortiz began learning to make pots when it started getting harder to find true ancient pots. So their first experiments turned out crude pottery but with a little work, their pots could be "antiqued" enough to pass muster as being ancient. Over a few years each modern potter got better and better until finally, their work could hardly be distinguished from the truly ancient. Then the Mexican Antiquities Act was passed and terror struck: because the old and the new could not be differentiated, potters were having all their property seized and their families put out of their homes because of "antiqued" pottery they made just yesterday. Things had to change almost overnight and several potters destroyed large amounts of their own inventory because it looked "antique." Then they went about rebooting the process and the product in Mata Ortiz.

For more info:

Mata Ortiz pottery at Wikipedia

Mata Ortiz at Wikipedia

Casas Grandes at Wikipedia

Contemporary Pottery

The term "contemporary" has several possible shadings in reference to Southwestern pottery. At some pueblos, it's more an indicator of a modern style of carving or etching than anything else. At San Felipe it refers to almost anything newly made there as they have almost no prehistoric templates to work from. At Jemez the situation resolved to where what makes a piece uniquely "Jemez" is the clay. Any designs on that clay can be said to be "contemporary."

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Sgraffito Designs

"Sgraffito" is from the Italian, meaning "to scratch." It's a technique wherein designs are scratched into the surface of a piece of pottery, generally with the use of a needle, dental tool or other sharp object. Also usually, the surface of the piece has been slipped with one color of clay and scratching through it reveals the design in a different color of clay. Some potters will slip a piece with layers of various colors of clay and the depth of their etching gives a color depth to their designs. Some will fire their pieces first, using the firing process to produce different effects in the clay. When they etch them after, the different depths they etch to also lend a color depth to their designs.

The sgraffito technique has been widely used in Europe for centuries but only came to the pueblos in the late 1960s. Even then, it's only really been developed at Jemez, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso and Ohkay Owingeh. At Santa Clara, Joseph Lonewolf and his father, Camilio Tafoya, and sister, Grace Medicine Flower, have been credited as being among the first to develop sgraffito. Corn Moquino was there, too, in those early days. At San Ildefonso, Juan Tafoya and Barbara Gonzales were among the first. At Ohkay Owingeh, Alvin Curran and Tom Tapia were among the first. Juanita Fragua was among the earliest at Jemez.

In Mata Ortiz, virtually anything goes and sgraffito has been widely used since the early 1970s. Again, some potters scratch their designs before firing, some after. Some scratch to add textured designs to an otherwise same-colored surface. Some carve and scratch and then fire. Some carve, paint and fire, then scratch... The tools they use vary from dental picks and exacto knives to nails, file handles and sharpened bicycle spokes.

Silveira Family and Teaching Tree - Mata Ortiz

Disclaimer: This "family and teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this grouping and arrange them in a generational order/order of influence. Complicating this for Mata Ortiz is that everyone essentially teaches everyone else (including the neighbors), so it's hard to get a real lineage of family/teaching. The general information available is scant. This diagram is subject to change as we get better info.

- Gregorio Goyo Silveira & Gloria Hernandez

- Estrella Silveira

- Fabiola Silveira

- Goyin Silveira & Graciela Martinez

- Tony Silveira & Lorena Lopez

- Jose Silveira & Socorro Sandoval

- Lila Silveira & Carlos Carillo

- Saul Silveira & Sulma Orozco

- Trinidad Trini Silveira

- Yadira Silveira & Roberto Olivas

- Nicolas Silveira & Genoveva Sandoval

- Armando Silveira & Tomasa Mora

- Arminda Silveira

- Octavio Tavo Silveira and Mirna Hernandez

- Silvia Silveira & Tomas Ozuna

- Veronica Silveira & Sabino Villalba

- Rojelio Silveira & Monserrat Mendoza

- Israel Silveira

- Rafael Silveira