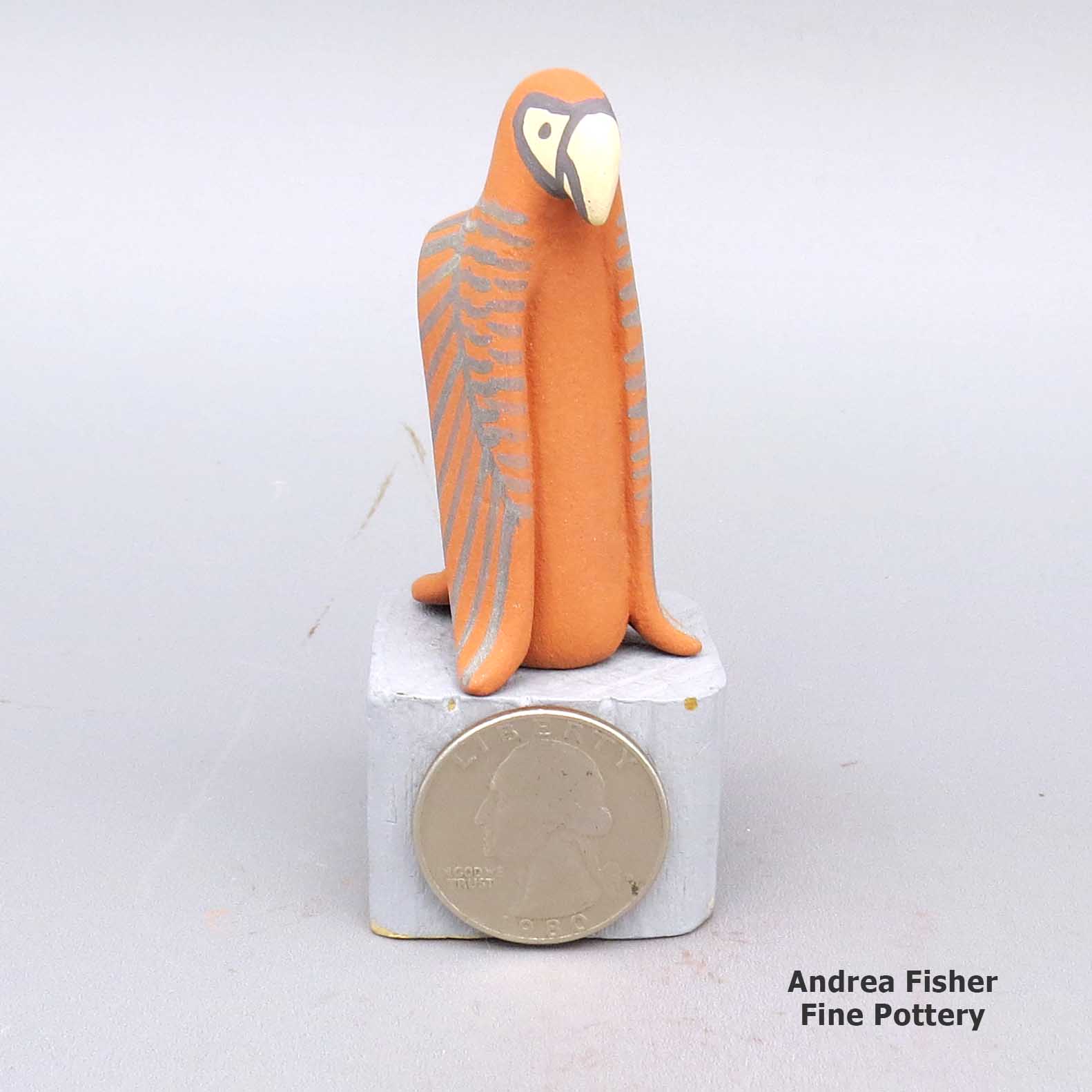

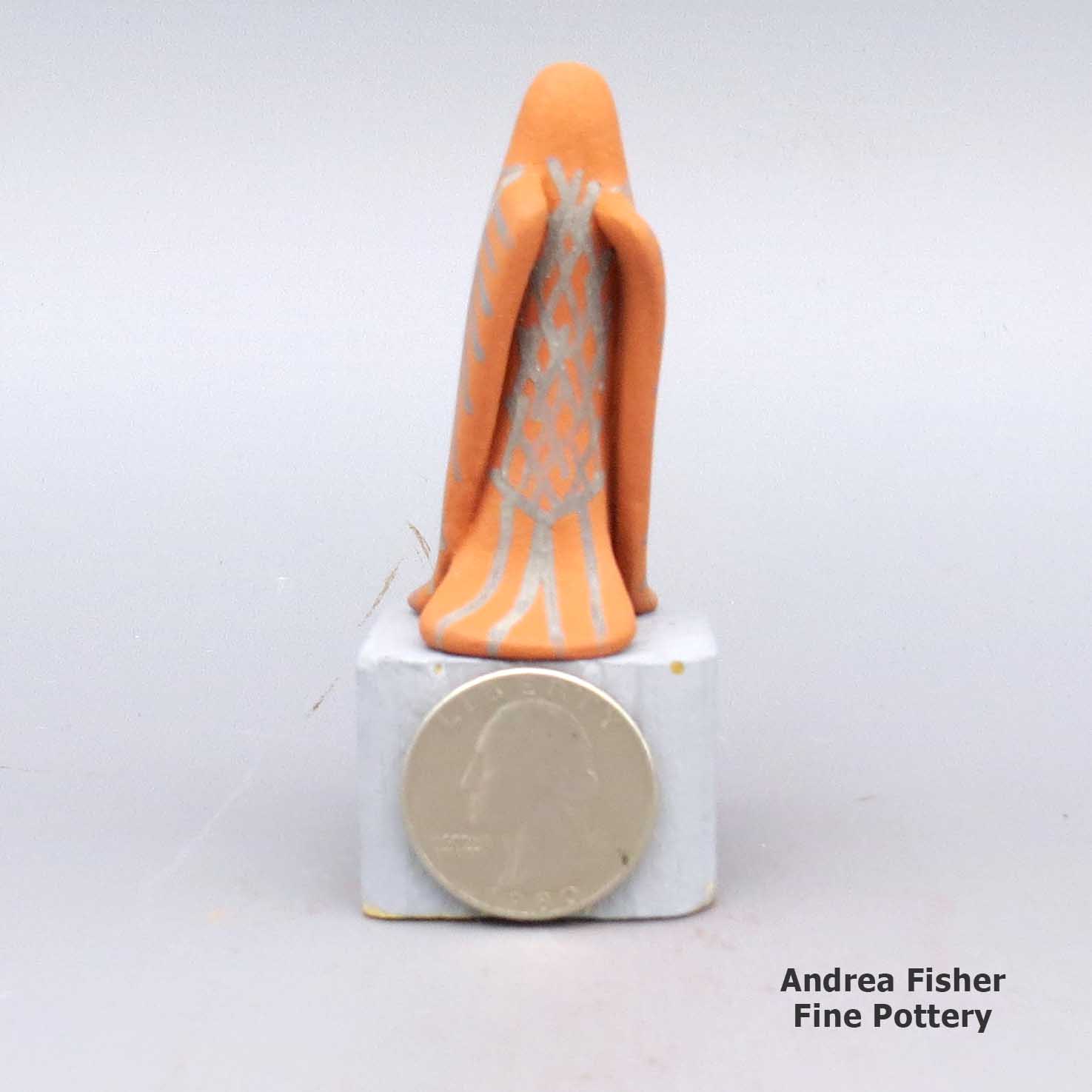

| Dimensions | 1 × 1 × 2.25 in |

|---|---|

| Measurement | Stand is shown for scale only |

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2022 |

| Signature | Loren WB Jemez |

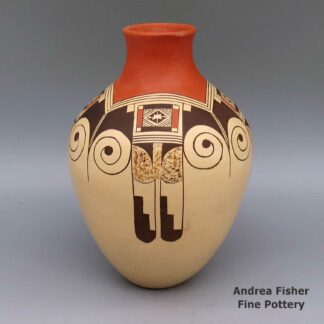

Loren Wallowing Bull, zzje2j010m24, Miniature polychrome standing parrot figure

$125.00

A miniature polychrome standing parrot figure

In stock

Brand

Wallowing Bull, Loren

Loren Wallowing Bull was born into Jemez Pueblo in April 1988. He was partly raised by Linda Lucero Fragua and Phillip Fragua. He showed an interest in working with clay early in life and his birth mother (Felicia Fragua) began teaching him the Jemez traditional way when he was about five years old. Like others of his generation in the Fragua family (Chrislyn, Amy, Anissa and Clifford), his feel for the clay goes way back.

Loren Wallowing Bull was born into Jemez Pueblo in April 1988. He was partly raised by Linda Lucero Fragua and Phillip Fragua. He showed an interest in working with clay early in life and his birth mother (Felicia Fragua) began teaching him the Jemez traditional way when he was about five years old. Like others of his generation in the Fragua family (Chrislyn, Amy, Anissa and Clifford), his feel for the clay goes way back.Loren has participated in shows at the Heard Museum, Eight Northern Pueblos Arts and Crafts Show, Tucson Art Museum and the Santa Fe Indian Market. At Santa Fe he earned a First Place ribbon in the Youth Pottery Division and he's earned a First Place ribbon at the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show.

Loren tells us he gets his inspiration from his family and, like them, he truly enjoys making pottery. His favorite shapes are eagles, as storyteller figures and in nativity scenes. He also says he likes to push the style envelope and come up with something new, something different. That's how he came up with his eagle Nativities and now he can't make enough of them. Then he moved into making storytellers and Nativities with owls, ravens, stellar jays, parrots...

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

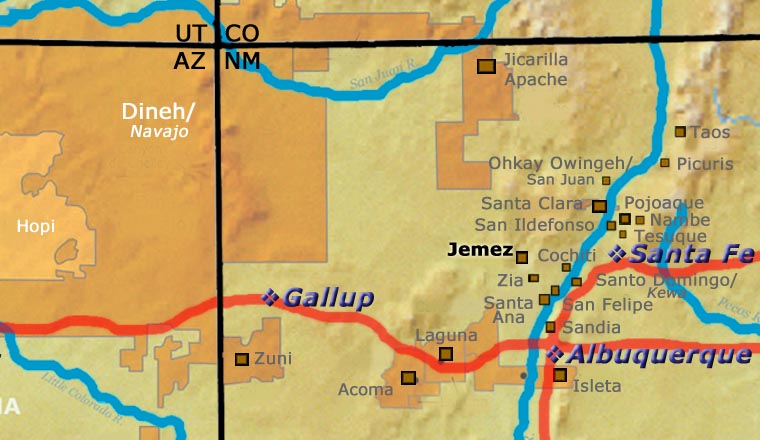

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Figures and Figurines

Generally, "Figure" denotes a real or mythic creature, like an owl or human or katsina or Corn Maiden. Whether form or decoration, all Puebloan pottery figures are meant to invoke particular spiritual essences. That's why "effigy" is used almost as often as "figure" to denote these pieces.

Among most Puebloans, the figure of an owl, for example, signifies all the physical and spiritual aspects attributed to the owl. It's a form of prayer to the spirit of "Owl" and the appropriately decorated physical form is meant to make that spirit manifest. However, to the Zuni people an owl is a good omen and to the Tewa people, an owl is a bad omen. Some potters at Santa Clara have made owls anyway, they just shaped and decorated them to reflect that "badness."

That explanation may make more sense in the case of the Corn Maiden as she is a mythic entity whose existence revolves around the most ubiquitous food staple in the Puebloan world: corn (maize). All representations of the Corn Maiden are meant to invoke her benevolence and abundance for their people. Because of her mythical/spiritual nature, different pueblos have slightly different physical forms for her but they all incorporate the basic form of a female human face on an ear of corn.

The potters of Tesuque turned out thousands of muna figures (also known as rain gods)for several decades, until they virutally burned out their pottery tradition. These muna had very specific shapes but were decorated with everything from micaceous slips to incised lines to polychrome geometric designs to poster paints. They were also made purely for domestic American consumption, sometimes delivered by the barrel to be used as prizes and giveaways.

The Storyteller is another figure based on Puebloan tradition: a tribal elder singing the stories of the tribe's oral history to the children. The original was based on the traditional cultural story: a grandfather singing his part of the story in his native language so the children learn both the language and their identity against the backdrop of that history. Shortly, the storyteller form was duplicated in several other pueblos, each pueblo's potters adapting the form to their local situation. In some places, the grandmother became the primary sex of their storytellers. At Jemez, that responsibility was shared between grandmothers and grandfathers. Then some potters in search of new niches in the marketplace branched into making "spirit figure" storytellers, like eagles, ravens, hummingbirds, cats and dogs. Some Zuni potters have made storyteller owls.

Similar to the Storyteller is the Story Time: a set of separate children displayed around a larger central singing figure.

The Nativity set (also known as nacimiento) is a set of figures based on the intersection of Puebloan mythologies and stories they heard from Christian missionaries. Those potters who make them also tend to favor dress, shapes and designs that reflect their own heritage(s). The first few nativities made at Tesuque Pueblo were decorated with Spanish colonial costumes but that soon changed and every nativity made since has a distinct blend of Native American and Christian, with no other reference to colonialism. The "Singing Angel" (a single standing figure with outstretched wings and hands clasped together in prayer) and "Flight to Egypt" (usually depicting Mary with a baby Jesus on the back of a donkey and a standing Joseph nearby holding the rein) are similar mixes of tribal and Christian figures. The miniature nativities made by Santa Clara/Dineh artist Linda Askan clearly show Dineh religious influence in the headresses worn by Joseph, the angel and the three wise men. At the same time, the Dineh Folk Art nativities made by Jonathan Chee are based on the realities of daily Dineh life: the three wise men wear wide-brim hats and blue jeans, and bring gifts of salt and 50-pound bags of flour.

Pueblo and Dineh artists also make a full zoo of domesticated, farm and wild animal figures: horses, donkeys, cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, turkeys, giraffes, elephants, dogs, cats, mermaids, women-dressed-up-and-taking-selfies and cowboys among them.

About Bird Elements

One of the main tenets of the Flower World ideology is that birds are messengers to and from Paradise. They carry our prayers to Heaven and they bring back the responses. Not all the pueblos accepted the Flower World ideology but it seems almost everyone, almost everywhere, agrees that birds are the messengers of Heaven. All pueblos do have multiple designs that incorporate feathers, if feathers aren't the main element of the design.

The Flower World ideology originated in central Mexico and most likely traveled north to the pueblos in the company of missionaries and long-distance traders. Turquoise was taken south while tropical birds, copper bells, seashells, and textiles (with particular spiritual designs on them), along with other spiritual items, were taken north. Going either way, almost everyone passed by Paquimé. The trade routes from the south came together there and the trade routes to the north diverged from there. That business didn't really come together until the first structures went up in the immediate vicinity of Paquimé, around 1150 CE. Then it ended around 1450 CE when the city was abandoned. That was also the end of pilgrims making their way south and then coming north again a few years later. For more than 300 years that traffic had been a major profit center and prestige generator for the people of Paquimé and Casas Grandes. After Paquimé was abandoned, though, the trade and pilrimage routes became far more dangerous. With the advent of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico, being a foreigner in that area became far more dangerous, too. Essentially, the puebloans who had embraced the Flower World ideology were cut off from their Holy Land.

The Flower World Complex, with its symbology, flowed across the American Southwest and eventually reached the Four Corners area. But it arrived at about the same time the kachina cults were coming together and the people were abandoning the Four Corners. The Flower World ideology was felt to be greater than what had come before so it's symbology was basically imprinted on top of that. Then the designs of the kachina cults and other clans were added on top of the Flower World symbology. Then came the Europeans with their designs and spiritual practices.

One of the principals of Native American design is that it is necessary only to note one part of most animals to imply the presence of the whole, especially when it comes to birds and bird elements. A lot of the design on Hopi pottery can only be described as "bird elements," although it is often possible to discern parrot feathers from eagle feathers, and eagletails from other bird's tails.

The Zunis have an ancient "almost-spiral" design that comes from the beaks of their equally ancient "rainbirds." The Zunis also like to make owl figures as owls are a symbol of wisdom to them. To some Northern Tewas, owls are creatures to be feared.

At Acoma they have a "cloudeater," a crane pictured with neck bent over and filling with fish shown sideways in its throat as it swallows them whole. Acoma potters also have a parrot that resembles the parrot found on the sides of the boxes carried by Amish traders back in the day. The parrot is not complete without a branch with leaves, and maybe berries, in its claws.

At Santo Domingo, religious dictates limit what can be imaged on pottery offered to the public. Birds, fish, turtles and flowers are allowed, along with a vast catalog of geometric designs. Images of humans are not. Next door at Cochiti, almost anything goes

The artists of the Mata Ortiz area are resurrecting some of the designs left behind by artists of old but they have no inner connection with the Flower World. Others in today's Mata Ortiz have gone totally contemporary: carving, scratching and painting beautiful images of birds with branches, vines and flowers.

Emilia Loretto Family Tree - Jemez Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Emilia Loretto (c. 1910s-) & Carmalito Loretto

- Grace L. Fragua (c. 1920s-) & Felix Fragua

- Bonnie Fragua (1966-)

- Jonathan Fragua (c. 1985-)

- Carol Fragua Gachupin & Joseph R. Gachupin Sr.

- Joseph E. Gachupin Jr.

- Cindy Fragua (1963-)

- Clifford Kim Fragua (1957-)

- Felicia Fragua (1964-) & Mike J. Curley

- Ardina Fragua (1980-)

- Loren Wallowing Bull (1988-)

- Linda Lucero Fragua & Phillip M. Fragua

- Chrislyn Fragua (1973-)

- Chrislyn Fragua (1973-)

- Rose Fragua (1942-2012)

- Janeth Fragua (1964-)

- Emily Fragua Tsosie (1951-2021) & Leonard Tsosie (1941-)

- Darrick Tsosie (1977-)

- Joseph L. Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Lorna Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Robert Tsosie (c. 1970s-)

- Bonnie Fragua (1966-)

- Angela Loretto

- Anthony Loretto (1969-)