| Dimensions | 4 × 4 × 5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, adhesive residue on bottom |

| Signature | Camilio Tafoya Santa Clara |

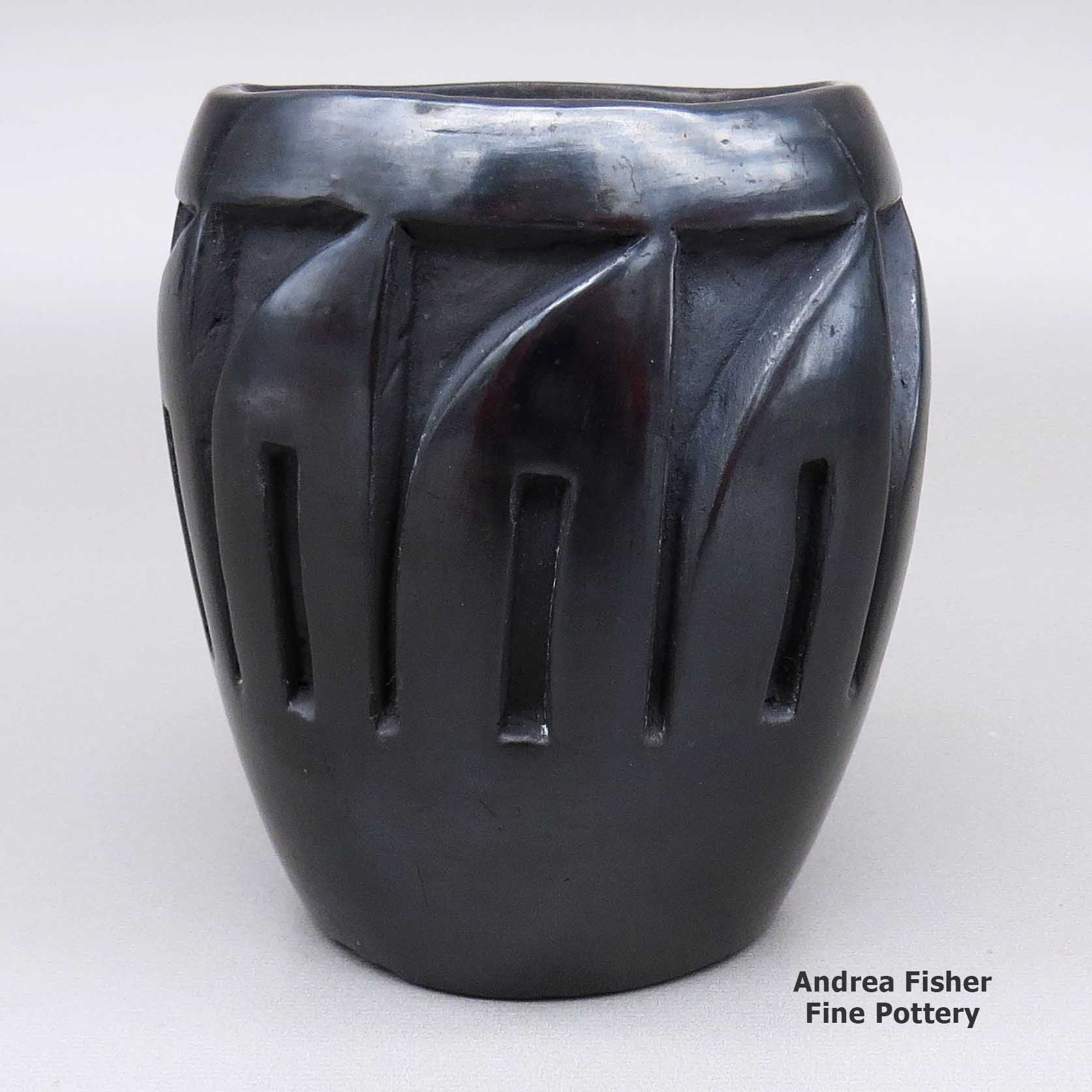

Camilio Tafoya, zzsc3b501, Black jar carved with a feather ring design

$550.00

A black jar carved with a ring of feathers design

In stock

Brand

Tafoya, Camilio

His father, a wood carver, taught him to carve and Camilio adapted that learning to the carving of pottery. He learned to make his clay coils thicker and allow the pots to dry harder before beginning to carve them. That solved the problem of carving too deeply and ruining a pot by carving through it. Using his method he learned to make very large carved jars.

Among his favorite designs to carve were the avanyu (the mythic Tewa water serpent), birds, flowers and bear paws. He also liked to carve ancient rock art designs he found while hiking in the hills and mountains around Santa Clara.

Joseph Lonewolf, Camilio's son, remembered his father taking him into the mountains and showing him around. Joseph was impressed by the petroglyphs they often came across. Camilio was able to translate the meanings of many of the designs so that Joseph could understand what the designs symbolized.

Variations of those carved designs reappeared many times over the years in the work of Camilio and later in Joseph's work. During those walks they also found many old pottery sherds, some painted, some incised, some carved, some corrugated, all ancient. That's where the great storehouse of Santa Clara designs is kept.

Camilio was one of the first men to become known as a potter in the pueblo. Many men helped their wives with different aspects of the process, like digging and processing the clay, scraping and sanding pots, gathering firewood and manure, firing the pots, etc., but Camilio did the whole process himself, from end to end.

His wife, Agapita Silva (1904-1959), was an accomplished potter when they married and they worked together for many years. Camilio and Agapita taught their son, Joseph Lonewolf, and daughter, Grace Medicine Flower, and daughter-in-law, Lucy Year Flower, to make pottery, too.

In the late 1960s, after his wife passed on, Camilio stopped making his large, carved pots and his famous sculptural horses. Instead, he, Joseph and Grace began developing the fine art of meticulously incising pottery now known as sgraffito. In that method, designs are scratched into the hard-dried surface of a pot before firing. Simple mistakes can ruin a pot. The amount of time and degree of meticulous work involved have made for increased prices for sgraffito-decorated pots.

In late 1968 Camilio began working closely with Grace, making many highly polished black and red seed pots decorated with intricate sgraffito work. In 1972 he went to work at Joseph's house and was busy making exceptional sgraffito art there almost until the day he died.

In 1985, along with his sister, Margaret Tafoya, and 42 other Santa Clara potters, Camilio participated in a show at the Sid Deutsch Gallery in New York City. He also participated in several gallery shows with his son Joseph in Sacramento and Santa Monica, California, and in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Camilio passed on in 1995.

Some Exhibits that featured Camilio's work

- Gifted! Recent Additions to the Heard Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. 2015

- Home: Native Peoples in the Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. 2005

- Breaking the Surface: Carved Pottery Techniques and Designs. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. 2005

- The Collecting Passions of Dennis and Janis Lyon. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. May - September 2004

- Every Picture Tells a Story. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. September 2002 - September 2005

- Recent Acquisitions from the Herman and Claire Bloom Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. January - July 1997 4th Annual Collectors Auction. Cameron Trading Post. Cameron, Arizona. October 27-29, 1989

- Celebrating the Spirit: Contemporary Native American Art. Felicita Foundation for the Arts. Mathes Cultural Center. Escondido, California. October 21 - November 30, 1985

- Joseph Lonewolf, Camilio Sunflower Tafoya, Pho-Sa-We: Presenting a New Collection of Their Incomparable Pottery Creations. Galeria Capistrano. San Juan Capistrano, California. September 26-28, 1980

- 1975 Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Safari Hotel Convention Center. Scottsdale, Arizona. March 12-15, 1975. Note: 13th Annual

- 1974 Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Safari Hotel Convention Center. Scottsdale, Arizona. March 6-9, 1974. Note: 12th Annual

- 1970 Scottsdale National Indian Arts Exhibition. Executive House. Scottsdale, Arizona. February 28 - March 8, 1970. Note: 8th Annual

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

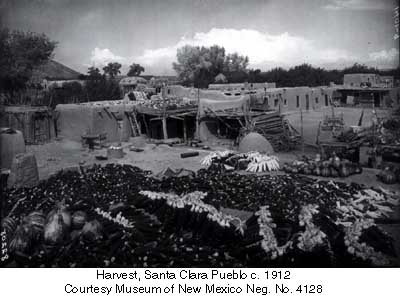

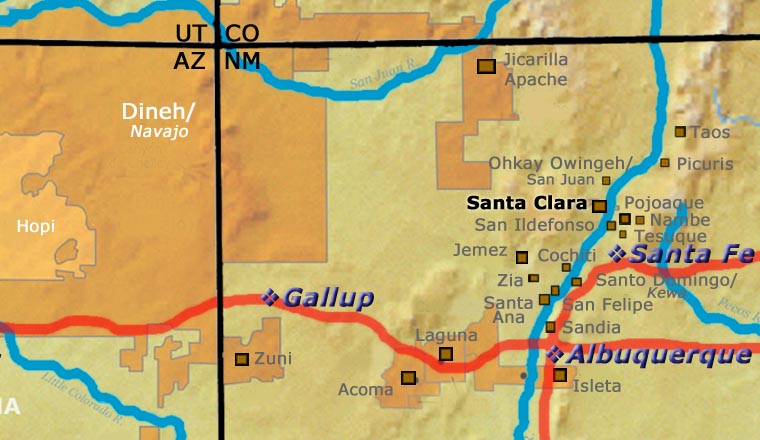

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

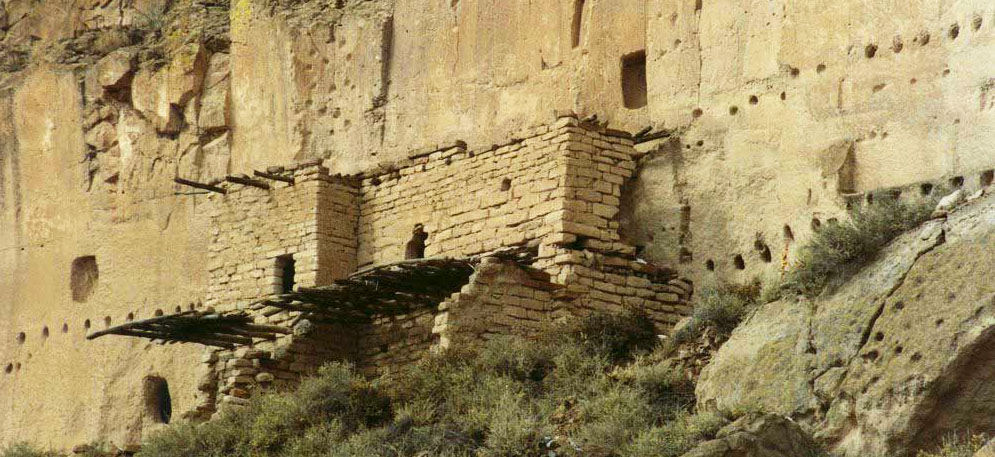

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Jars

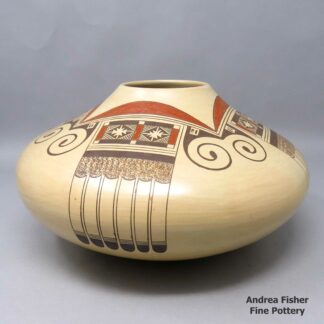

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

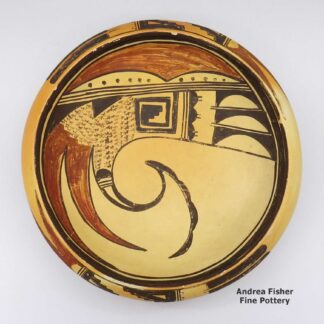

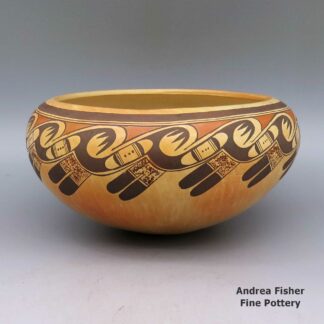

About Bird Elements

One of the main tenets of the Flower World ideology is that birds are messengers to and from Paradise. They carry our prayers to Heaven and they bring back the responses. Not all the pueblos accepted the Flower World ideology but it seems almost everyone, almost everywhere, agrees that birds are the messengers of Heaven. All pueblos do have multiple designs that incorporate feathers, if feathers aren't the main element of the design.

The Flower World ideology originated in central Mexico and most likely traveled north to the pueblos in the company of missionaries and long-distance traders. Turquoise was taken south while tropical birds, copper bells, seashells, and textiles (with particular spiritual designs on them), along with other spiritual items, were taken north. Going either way, almost everyone passed by Paquimé. The trade routes from the south came together there and the trade routes to the north diverged from there. That business didn't really come together until the first structures went up in the immediate vicinity of Paquimé, around 1150 CE. Then it ended around 1450 CE when the city was abandoned. That was also the end of pilgrims making their way south and then coming north again a few years later. For more than 300 years that traffic had been a major profit center and prestige generator for the people of Paquimé and Casas Grandes. After Paquimé was abandoned, though, the trade and pilrimage routes became far more dangerous. With the advent of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico, being a foreigner in that area became far more dangerous, too. Essentially, the puebloans who had embraced the Flower World ideology were cut off from their Holy Land.

The Flower World Complex, with its symbology, flowed across the American Southwest and eventually reached the Four Corners area. But it arrived at about the same time the kachina cults were coming together and the people were abandoning the Four Corners. The Flower World ideology was felt to be greater than what had come before so it's symbology was basically imprinted on top of that. Then the designs of the kachina cults and other clans were added on top of the Flower World symbology. Then came the Europeans with their designs and spiritual practices.

One of the principals of Native American design is that it is necessary only to note one part of most animals to imply the presence of the whole, especially when it comes to birds and bird elements. A lot of the design on Hopi pottery can only be described as "bird elements," although it is often possible to discern parrot feathers from eagle feathers, and eagletails from other bird's tails.

The Zunis have an ancient "almost-spiral" design that comes from the beaks of their equally ancient "rainbirds." The Zunis also like to make owl figures as owls are a symbol of wisdom to them. To some Northern Tewas, owls are creatures to be feared.

At Acoma they have a "cloudeater," a crane pictured with neck bent over and filling with fish shown sideways in its throat as it swallows them whole. Acoma potters also have a parrot that resembles the parrot found on the sides of the boxes carried by Amish traders back in the day. The parrot is not complete without a branch with leaves, and maybe berries, in its claws.

At Santo Domingo, religious dictates limit what can be imaged on pottery offered to the public. Birds, fish, turtles and flowers are allowed, along with a vast catalog of geometric designs. Images of humans are not. Next door at Cochiti, almost anything goes

The artists of the Mata Ortiz area are resurrecting some of the designs left behind by artists of old but they have no inner connection with the Flower World. Others in today's Mata Ortiz have gone totally contemporary: carving, scratching and painting beautiful images of birds with branches, vines and flowers.

Sara Fina Tafoya Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Note: Sara Fina (Gutierrez) Tafoya was the older sister of Pasqualita Gutierrez. Pasqualita was born the same year Sara Fina married Geronimo Tafoya and their mother died shortly after. Sara Fina and Geronimo essentially raised Pasqualita.

- Sara Fina Tafoya (1863-1949) & Geronimo Tafoya

- Margaret Tafoya (1904-2001) & Alcario Tafoya (d. 1995)

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Barry Archuleta

- Bryon Archuleta

- Sheila Archuleta

- Jennie Trammel (1929-2010)

- Karen Trammel Beloris

- Virginia Ebelacker (1925-2001)

- James Ebelacker (1959-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Jamelyn Ebelacker

- Sarena Ebelacker

- Richard Ebelacker (1946-2010) & Yvonne Ortiz

- Jason Ebelacker

- Jerome Ebelacker & Dyan Esquibel

- Andrew Ebelacker

- Nicholas Ebelacker

- James Ebelacker (1959-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Lee Tafoya (1926-1996) & Betty Tafoya (Anglo)(1933-1988)

- Linda Tafoya (Oyenque)(Sanchez) (1962-)

- Antonio Jose Oyenque

- Jeremy Rio Oyenque

- Maria Theresa Oyenque

- Melvin Ray Tafoya (1957-)

- Phyllis Bustos Tafoya

- Linda Tafoya (Oyenque)(Sanchez) (1962-)

- Mela Youngblood (1931-1990) & Walt Youngblood

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Christopher Cutler

- Joseph Lugo

- Sergio Lugo

- Nathan Youngblood (1954-)

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Toni Roller (1935-) & Ted Roller

- Brandon Roller

- Cliff Roller (1961-)

- Deborah Morning Star Roller

- Jeff Roller (1963-)

- Jordan Roller (1987-)

- Ryan Roller

- Susan Roller Whittington (1955-)

- Charles Lewis (1972-)

- Tim Roller (1959-)

- William Roller

- LuAnn Tafoya (1938-) & Sostence Tapia

- Michele Tapia Browning (1960-)

- Ashley Browning

- Mindy Browning

- Daryl Duane Whitegeese (1964-) & Rosemary Hardy

- Samantha Whitegeese

- Tina Whitegeese

- Michele Tapia Browning (1960-)

- Shirley Cactus Blossom Tafoya (1947-)

- Meldon Wayne White Eagle Tafoya & Diana Tafoya

- Andrea Tafoya (1985-)

- Crystal Tafoya (1981-)

- Melissa Tafoya

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Christina Naranjo (1891-1980) & Jose Victor Naranjo (1895-1942)

- Mary Cain (1916-2010) & Willie Cain

- Billy Cain (1950-)

- Joy Cain (1947-)

- Linda Cain (1949-)

- Autumn Borts-Medlock (1967-)

- Tammy Garcia (1969-)

- Tina Diaz (1946-)

- Warren Cain (1951-)

- Douglas Tafoya

- Marjorie Tafoya Tanin

- Mary Louise Eckleberry (1921-2003)

- Darlene Eckleberry

- Victor (1958-) & Naomi Eckleberry (1961-)

- Teresita Naranjo (1919-1999)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Denise Chavarria (1959-)

- Joey Chavarria (1964-1987)

- Loretta Sunday Chavarria (Singer) (1963-)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Cecilia Naranjo & James Lee McLean

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Ira Atencio (1975-)

- Lawrence Thunder Atencio

- Judy Tafoya (1962-) & Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Cecilia Fawn Tafoya (1986-)

- Chelsea Tafoya

- Eli Tafoya (1991-)

- Josetta Tafoya (1993-)

- Lincoln A. Tafoya (1989-)

- Linette Tafoya (1989-)

- Sarah Ayla Tafoya (1987-)

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Mida Tafoya (1931-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Kimberly Garcia (1978-)

- Cookie Kathleen Tafoya (1963-)

- Robert Maurice Moe Tafoya

- Donna Tafoya (1952-)

- Mike Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis Tafoya (1955-) & Matthew Tafoya (1953-)

- Lorraine Tafoya

- Matthew Tafoya Jr.

- Sabina Tafoya

- Sherry Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis & Marlin Hemlock (Seneca)

- Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo & Gracie Naranjo (Dineh)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo Jr.

- Teresa Naranjo

- Tracy Naranjo

- Mary Cain (1916-2010) & Willie Cain

- Camilio Tafoya (1902-1995) & Agapita Silva (1904-1959)

- Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012) & Joe Tafoya

- Kelli Little Kachina (1967-2014)

- Myra Little Snow (1962-)

- Forrest Red Cloud Tafoya

- Shawn Tafoya (1968-)

- Joseph Lonewolf (1932-2014) & Katheryn Lonewolf

- Greg Lonewolf (1952-)

- Rosemary Apple Blossom Lonewolf (1954-) & Paul Speckled Rock (1952-2017)

- Adam Speckled Rock

- Susan Romero & Mike Romero

- Grace Medicine Flower (1938-)

- Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012) & Joe Tafoya

- Dolorita Padilla (1897-1960) & Alberto Padilla (1898-)

- Manuel Tafoya (c. 1895-1958) (Painted pots for Sara Fina and for Margaret)

- Tomasita Tafoya Naranjo (1884-1918) & Agapito Naranjo (1880-1958)

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

- Adele Naranjo

- Howard & Linda Naranjo

- Charlotte Naranjo Suina

- Roberta Naranjo

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

- Juan Isidro Tafoya & Valerie Sisneros Isidro (Ohkay Owingeh)