Martinez, Maria

Undoubtedly the world’s most famous Native American potter, Maria Montoya Martinez was born in the Tewa pueblo of San Ildefonso around 1887. Back in those days records were maintained by the church and as far as they were concerned, no one was born until they were baptised. Maria’s baptism certificate says 1887, she herself thought she might have been 7 by then.

As she grew up, Maria observed her aunt, Nicolasa, making pottery. She was very interested and learned the basics of the traditional art of pottery making through watching and working with her.

In the early years of her career, Maria produced the traditional polychrome pottery of her village, generally black and terra cotta decorations painted on a background of white or tan. She shaped her pots the age-old way, by carefully hand-coiling and pinching the clay, then smoothing the inner and outer surfaces with gourd scrapers. However, Maria wasn’t happy with her own painting skills so she went to others to have any decorations added.

Early on her pots were recognized as the thinnest and most beautifully shaped pots being made at San Ildefonso. She had no trouble finding painters to decorate her pieces. Then the man who became her husband, Julian Martinez, an accomplished painter of hides, paper and walls, began decorating more and more pots for her. Then he worked with her in the firing of them.

Maria and Julian were married in 1904. From the beginning of their relationship they were traveling to demonstrate their craft at various fairs and expositions. They spent their honeymoon in 1904 demonstrating traditional San Ildefonso pottery making at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition at the St. Louis Worlds Fair.

They demonstrated their crafts again at the Panama California Expo in San Diego in 1915, the Chicago Worlds Fair in 1934, and the Golden Gate International Expo in 1939.

Native American craft fairs provided other marketing opportunities, and when she began signing her work, Maria both heightened her visibility and commanded higher prices. In 1954, she was awarded the Craftsmanship Medal, the highest honor awarded by the American Institute of Architects.

Contrary to legend implying that Maria “discovered” the black pottery process, Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett, Professor of Archaeology at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and Director of the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, found sherds of prehistoric black pottery while excavating in the ruins of Tsankawi (a non-contiguous part of Bandelier National Monument) in 1908. Tsankawi was an ancestral home of the San Ildefonso people.

To preserve and showcase that ancient product, Hewett went to San Ildefonso Pueblo and sought a skilled pueblo potter who could re-create that ancient style for him. Everyone he asked referred him to Maria. Together they worked out a deal and he pre-ordered (and paid for up front) a series of black pots from her.

When he returned, two years later, she had some black pots to show him. She wasn’t very happy with them but Hewett and his students were. They bought everything she had, even the ones she’d hidden under her bed. Then they commissioned more and paid for them, again in full and up front.

That led to several years of experimentation, until Maria and Julian were satisfied with their results in not just recreating that style of blackware but in going a step further. Their method required smothering the fire with manure during the firing process, effectively creating an “oxygen-reduction process” that turned the would-be-red pots black.

Julian worked out the other half of the “black-on-black” process when he began painting his designs “in the negative,” using a matte black paint on the polished pot surface to create his decorations. Once fired, that demonstrated the technique that has become so famous today.

According to Susan Peterson in The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez, the six distinct steps involved in the creation of blackware pottery include, “finding and collecting the clay, forming a pot, scraping and sanding the pot to remove surface irregularities, applying the iron-bearing slip and burnishing it to a high sheen with a smooth stone, decorating the pot with another slip, and firing the pot.”

Julian faced a challenge in attempting to decorate Maria’s pots. The process he finally settled on involved polishing the background first and then applying the matte slip to outline the decoration and fill in the background. In 1918, Julian finished their first decorated blackware pot with a matte black background and a polished avanyu (horned water serpent) design. Many of Julian’s decorations were patterns adopted from ancient vessels of the pueblos. Some of the patterns consisted of feathers, birds, road runner tracks, deer tracks, rain, clouds, mountains, lightning bolts and kiva steps.

As her pots attracted more and more attention for their unique beauty, Maria began to slowly raise her prices. With the demand for her pots growing, she realized that her work could enrich the lives of the people of her pueblo, artistically and economically.

After the Spanish flu pandemic passed through in 1918-1919, the pueblo was reduced to less than 90 members. Maria’s efforts back then virtually saved her people. In the ages-old puebloan manner, she generously shared her techniques with others. Maria became the matriarch of a “craft lineage” that continues today. In a career that spanned seven decades, her pottery brought honors and acclaim, revitalizing the art and the economy of San Ildefonso Pueblo.

Even though Julian decorated the pots, Maria claimed all the work in the early years because pottery was still considered a woman’s job in the pueblo. Maria started to sign her pottery with “Marie” in 1922. She signed “Marie” because Kenneth Chapman, Director of the Museum of New Mexico, had convinced her “Marie” was a name more familiar to the Anglo buying public than “Maria” and should command higher prices.

They left Julian’s signature off their pieces to respect the norms of Pueblo culture until 1926. Then Maria decided that since Julian was doing half the work, as the painter he should get half the credit. After that, “Marie + Julian” was the official signature on their pottery until Julian’s death in 1943.

Maria’s family began helping more with the pottery business after Julian died. From 1943 to 1956 Maria’s son Adam took over collecting clay and materials for firing while his wife Santana took over painting decorations. “Marie + Santana” was the signature on their pots. These years were also Maria’s most prolific years.

Maria’s younger son, Popovi Da, spent four years in the US Navy after World War II. In 1950 he returned to San Ildefonso and, at the urging of Maria, began learning to paint with Santana. In 1956 he agreed to do Maria’s painting for her. That’s when Santana went back to her home and began working with Adam under their name. The signature on Maria’s pots became “Maria/Popovi”, until 1971 when Popovi passed on. Maria didn’t make another piece after his death.

Popovi had also often been busy with tribal politics during those years and, at times, couldn’t keep up with painting Maria’s pots. As Maria almost never painted a pot, those pots are plain and signed “Maria Poveka” (Poveka being her Tewa name, meaning: “pond lily”).

Today, values on Maria’s work vary based on the signature on the bottom, those with “Maria + Popovi” being among the most valued of all Pueblo pottery. After making pots for almost 80 years, Maria passed on in 1980.

Showing all 12 results

-

Maria Martinez, cjsi3c238, Black-on-black bowl with geometric design

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

Maria Martinez, lksi2l313: Black-on-black plate with feather ring geometric design

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

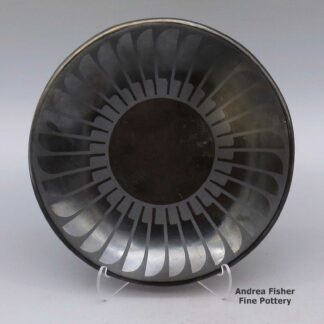

Maria Martinez, rosi3d140, Black bowl with a geometric design

$3,500.00 Add to cart -

Maria Martinez, rosi3d141, Black-on-black bowl with geometric design

$4,900.00 Add to cart -

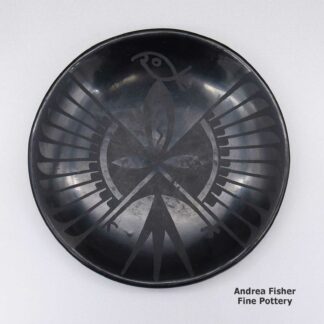

Maria Martinez, spsi3b090, Black-on-black plate with bird design

$950.00 Add to cart -

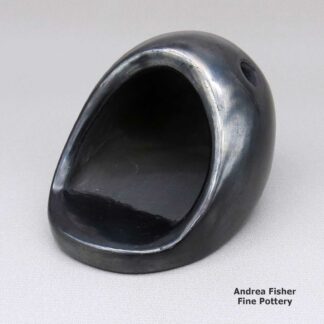

Maria Martinez, thsi3b011, Polished black horno

$1,100.00 Add to cart -

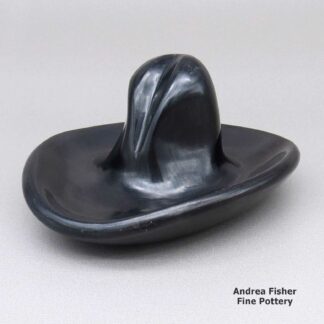

Maria Martinez, zzsi3a030, Black cowboy hat

$1,800.00 Add to cart -

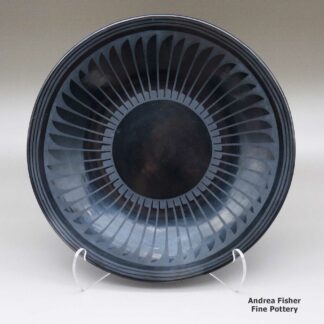

Maria Martinez, zzsi3b544, Plate with a geometric design

$8,200.00 Add to cart -

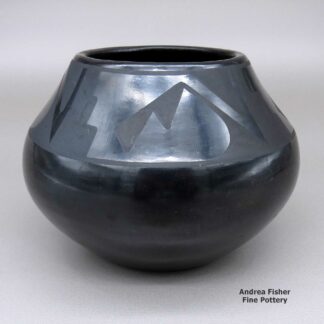

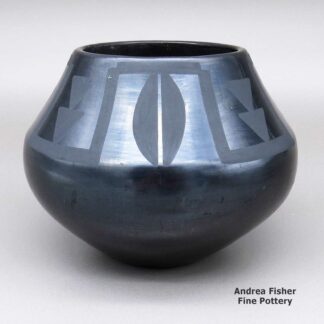

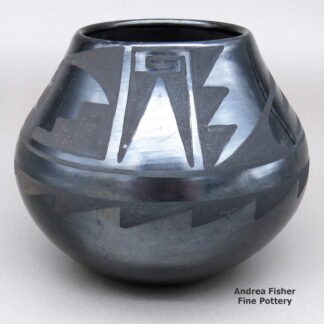

Maria Martinez, zzsi3b545, Jar with a geometric design

$4,800.00 Add to cart -

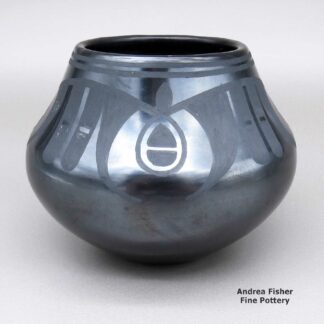

Maria Martinez, zzsi3b546, Bowl with a geometric design

$4,500.00 Add to cart -

Maria Martinez, zzsi3c130, Jar with geometric design

$3,800.00 Add to cart -

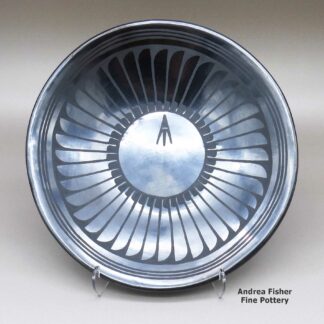

Maria Martinez, zzsi3c131, Plate with ring-of-feathers design

$7,800.00 Add to cart

Showing all 12 results