Traditional Zuni Design

Traditional Zuni Designs

Anthropologists say the Zuni people have been isolated for so long, there are no referrents to where their language came from. The images they paint on pottery, though, show some signs of cross-pollination with the Hopi, Acoma, Laguna and some of the Rio Grande pueblos.

Among those images are the heart-line, as in deer-with-heart-line. At some pueblos, that has become bear-with-heart-line and antelope-with-heart-line. Sometime around 1890, a Laguna potter made the journey to Zuni to learn from a potter there how to make better pottery. He stayed only a few months before returning to Laguna, via Acoma. He brought back better knowledge of mixing the clay, making the paints and painting the designs. Among those designs was the deer-with-heart-line.

At the time of first Spanish contact, there were seven Zuni pueblos spread out along the Zuni River. By about 1720, that was reduced to one. When the American archaeologists arrived, they set about excavating almost every abandoned village they could find. In the process, many pieces of ancient pottery came to light. That's where the names Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff (matte paint on white and red slips, produced from about 1375 CE to about 1700 CE), Kwakina Polychrome (glaze paint on a white slip, produced from about 1325 to about 1400) and Heshotauthla Black-on-red and Polychrome (glaze decorations, produced from about 1275 to about 1400) came from. A primary difference between Kwakina and Heshotauthla designations is the color the inside of the bowl is slipped with. The decorations on both are painted with lead glaze colors and are taken from the same design library, which includes many designs common to the Mogollon Highlands in eastern Arizona (such as St. Johns Polychrome), although the designs tend to be not as well executed.

The advent of Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff coincides with the entrance of an immigrant community from the north: the land of the Hopi. With them came the basic design library of what we now refer to as "Sikyatki Polychrome." Production of Kwakina- and Heshotauthla-style pottery dropped off quickly after the arrival of those who produced the Matsaki styles. It was around that time, too, that the Zuni villages around the Zuni Mountains were abandoned and the people pulled back to the pueblos along the lower Zuni River.

After Spanish contact and conquest, the Zunis were reduced to about one-tenth their population by Spanish diseases and labor practices. Before too long, they were gathered together in one village near the bank of the Zuni River. Their image catalog changed, too. When the American archaeologists and ethnologists came, they removed virtually every artifact of Zuni history they could dig up or find otherwise. Then they spirited it all away to storerooms on either coast, where most of it remains in boxes in dingy basement rooms today.

In 1986, Josephine Nahohai and several members of her family traveled to Washington DC and explored the basement storage shelves of the Smithsonian Institute, copying every ancient Zuni shape and design they found into their notebooks. When they returned to Zuni, their drawings became the basis for many of what are now referred to as traditional Zuni designs. Among those designs are symbols for mountains and forest, and images of frogs, tadpoles, dragonflies, serpents and rainbirds. Other Zuni potters have since visited other storerooms of ancient Zuni pottery and brought drawings of those shapes and designs back to the pueblo, too.

Showing 1–12 of 22 results

-

Agnes Peynetsa, ppzu3c030, Jar with deer-with-heart-line and geometric design

$625.00 Add to cart -

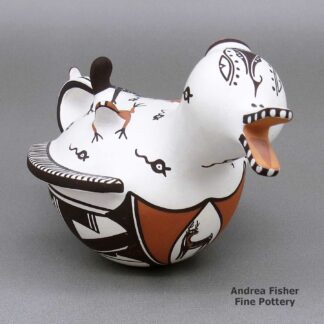

Agnes Peynetsa, zzzu3b515, Duck pot with a deer with heart line design

$395.00 Add to cart -

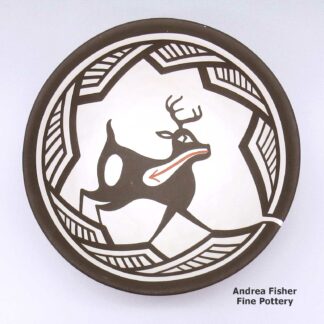

Alan Lasiloo, zzzu3b516, Bowl with deer-with-heart-line design

$350.00 Add to cart -

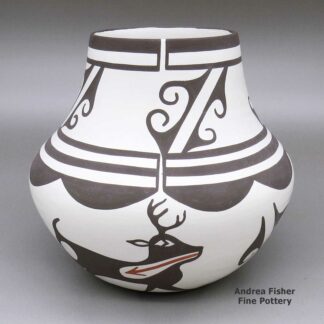

Alan Lasiloo, zzzu3b518, Jar with deer-with-heart-line design

$650.00 Add to cart -

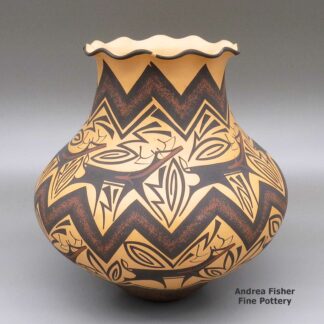

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu2m052, Polychrome jar with bird, fine line, and geometric design

$1,800.00 Add to cart -

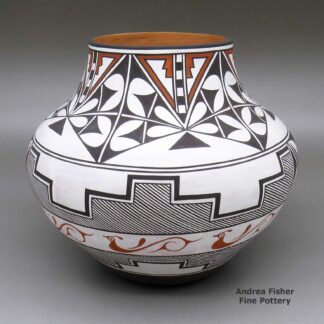

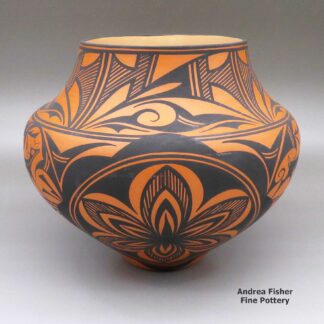

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu2m140, Polychrome jar with medallion, bird and geometric design

$2,600.00 Add to cart -

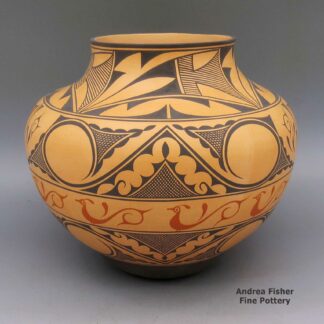

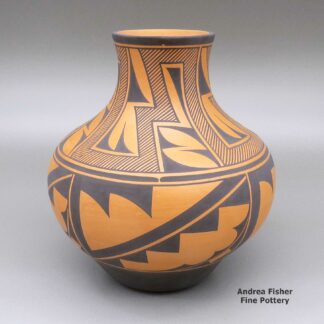

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3a301, Red and black jar with a geometric design

$850.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3b073, Polychrome jar with a frog, dragonfly, and geometric design

$275.00 Add to cart -

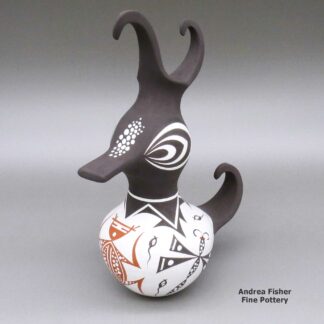

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3c030m1, Duck jar with geometric design

$850.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3c031, Polychrome jar with a geometric design

$1,450.00 Add to cart -

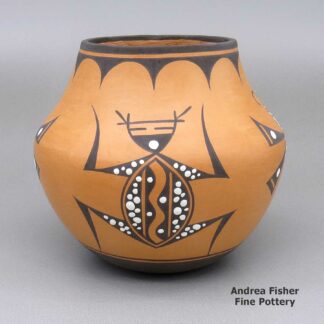

Anderson Peynetsa, cjzu3c274, Jar with deer-with-heart-line and geometric design

$1,600.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Peynetsa, mvzu3b099, Red and black jar with a deer with heart line and geometric design

$1,950.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 22 results