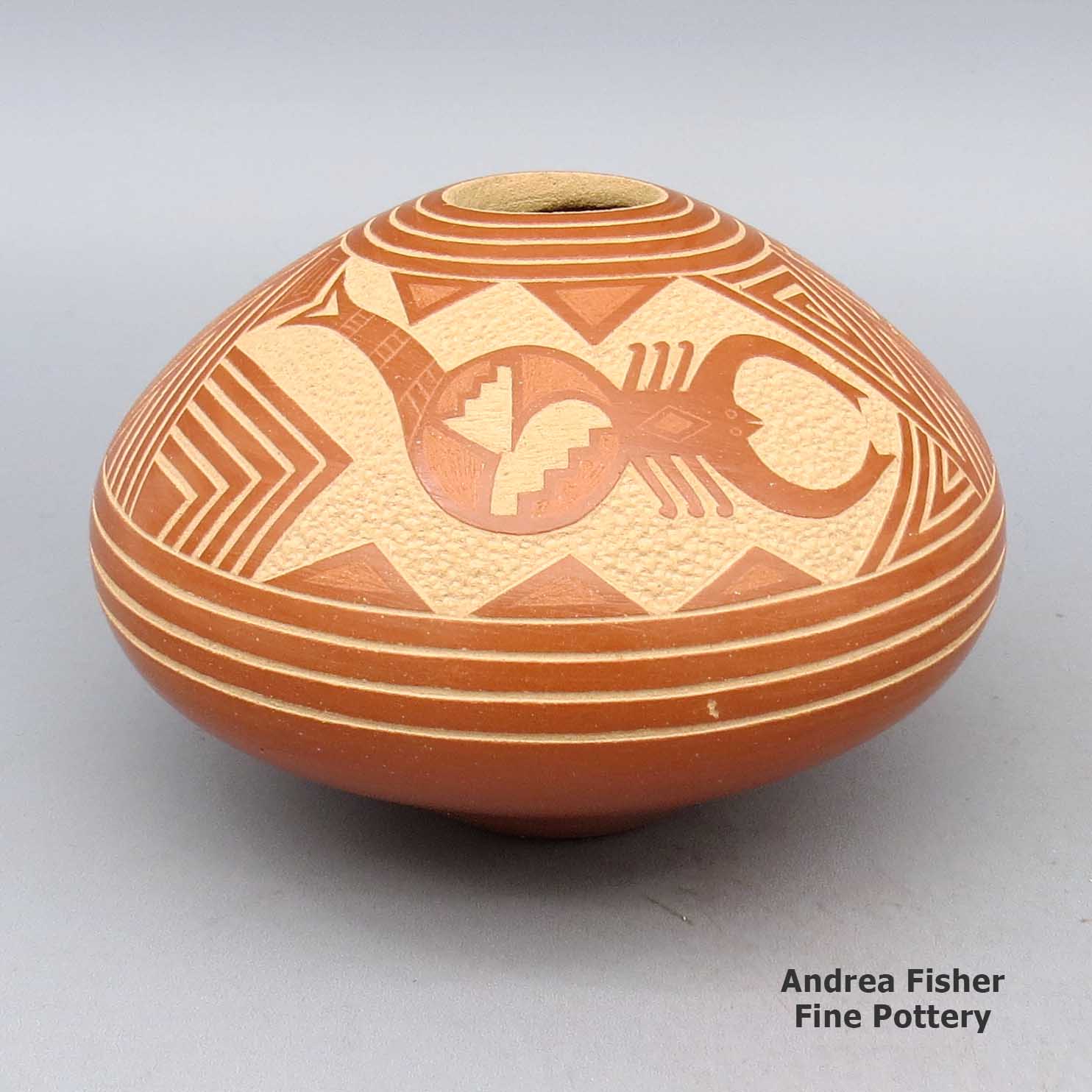

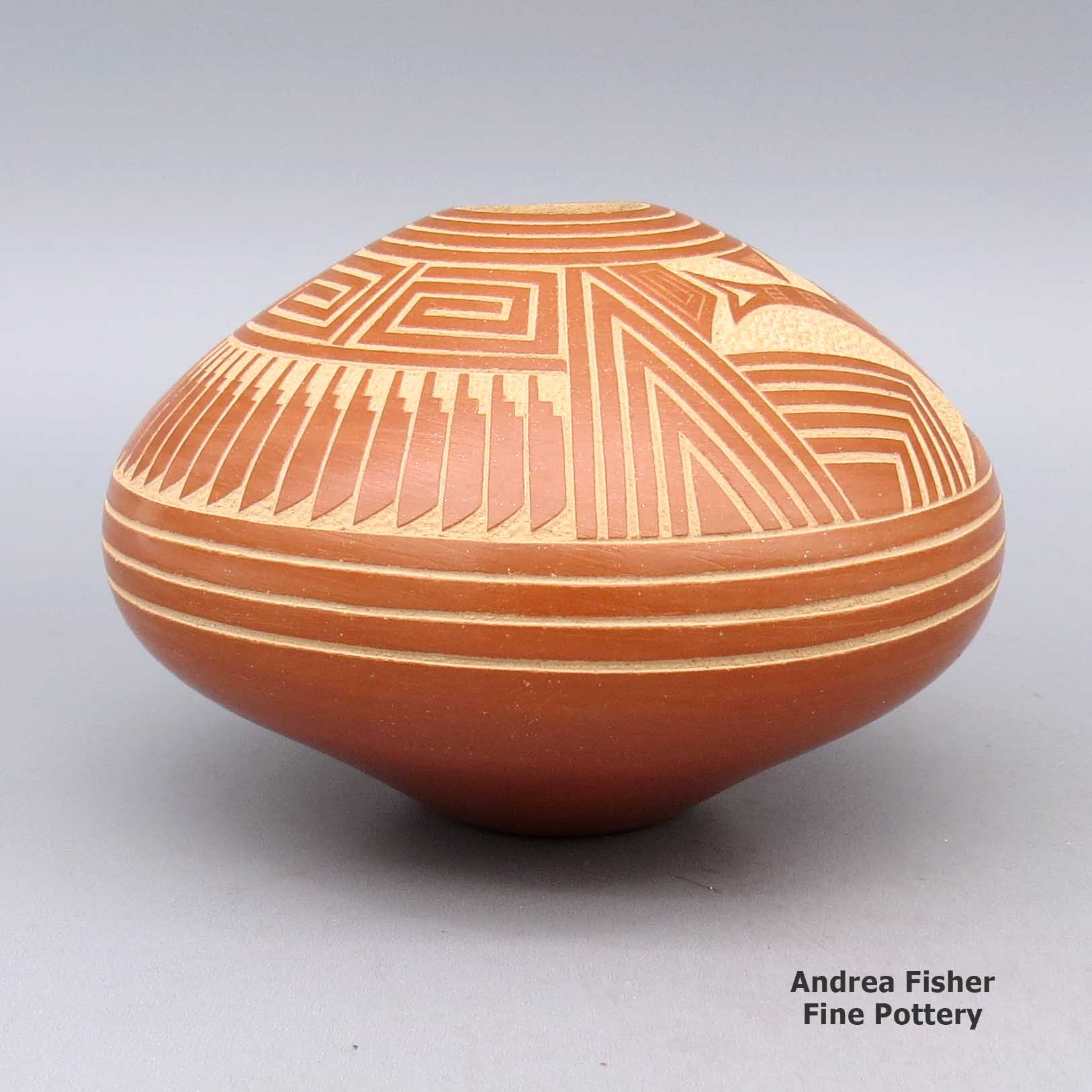

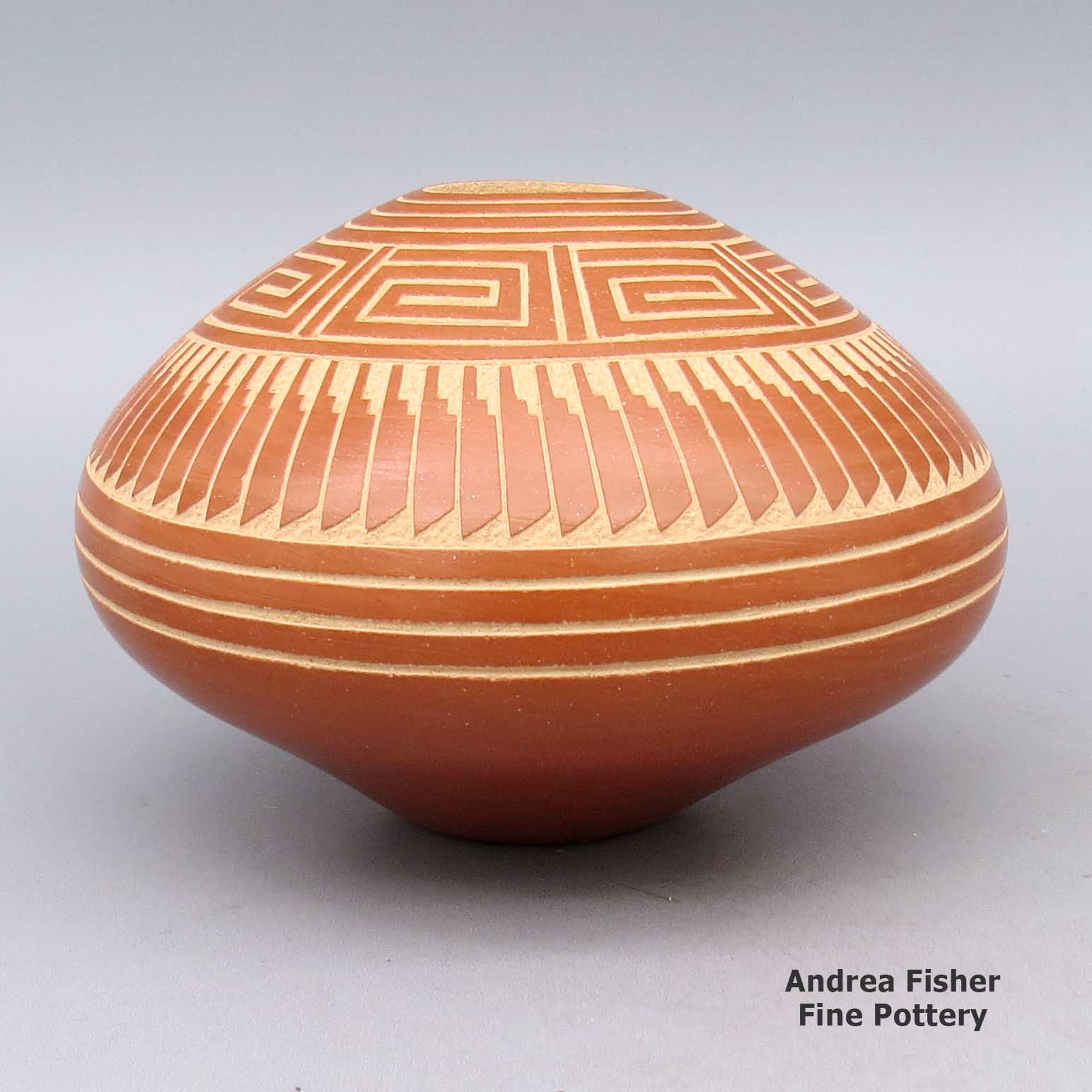

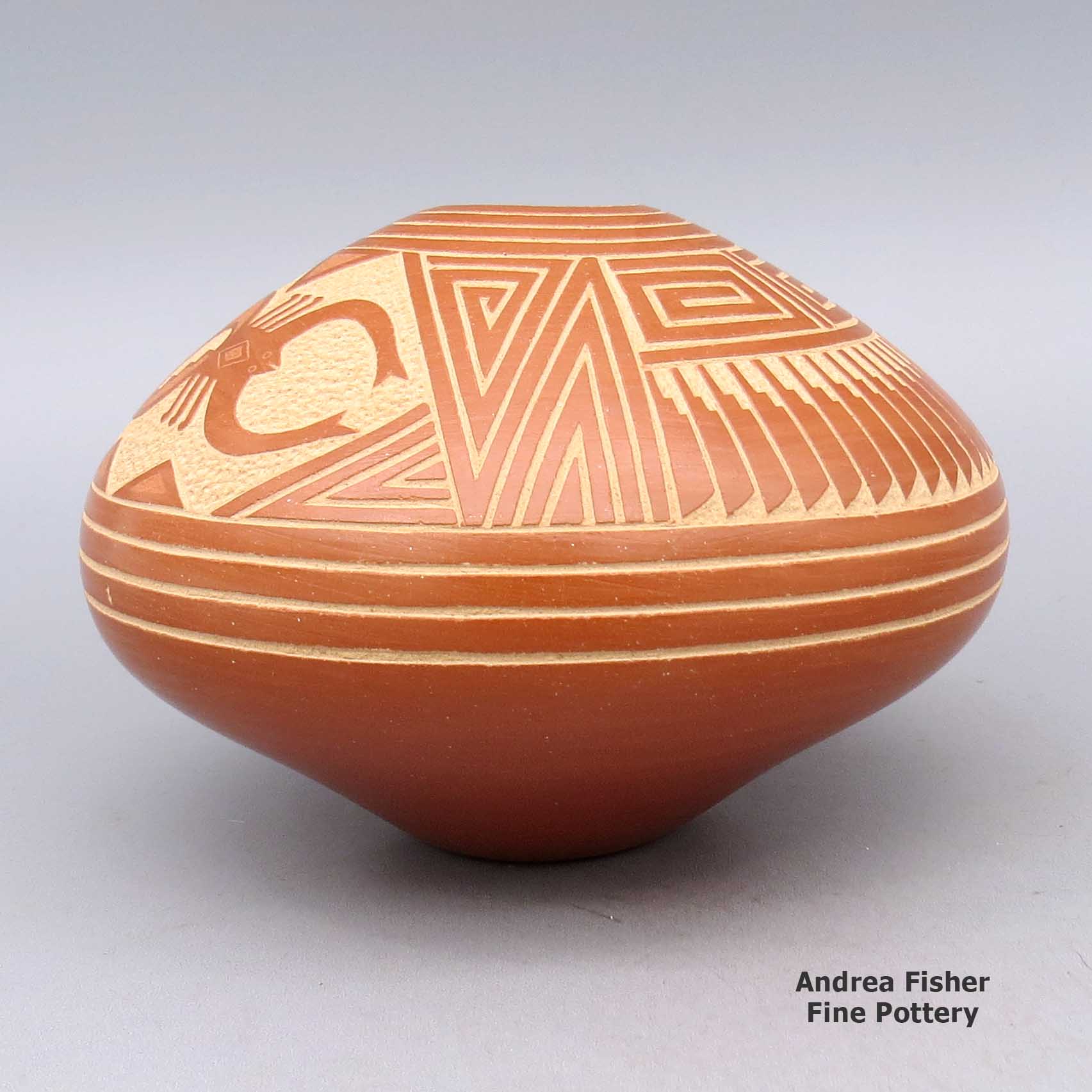

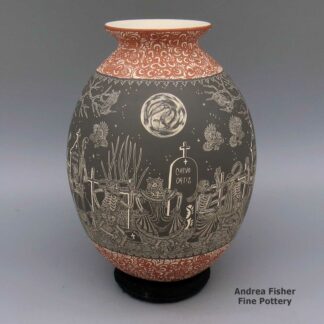

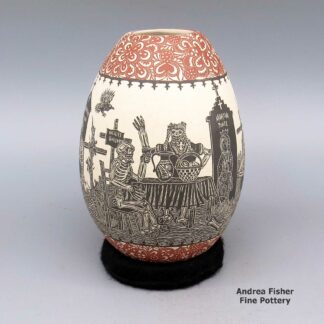

| Dimensions | 4.25 × 4.25 × 3 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Dennis Daubs Jemez |

Dennis Daubs, cmje2l084, Red jar with sgraffito geometric design

$525.00

A red jar decorated with a sgraffito Mimbres-Revival scorpion, ring-of-feathers and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Daubs, Dennis

Dennis Daubs (Oboweya: "Early morning runner before the kachina dance") was born into Jemez Pueblo in 1960. Inspired by his grandmother, Elvira Gachupin, and his great-grandmother, Maria Sanchez, he started gathering clay and experimenting with making pottery when he was 18. He soon decided to specialize in making red or black polished pottery and decorating it with sgraffito designs. His sgraffito designs usually include detailed animals and kachina dancers with various geometric designs around them.

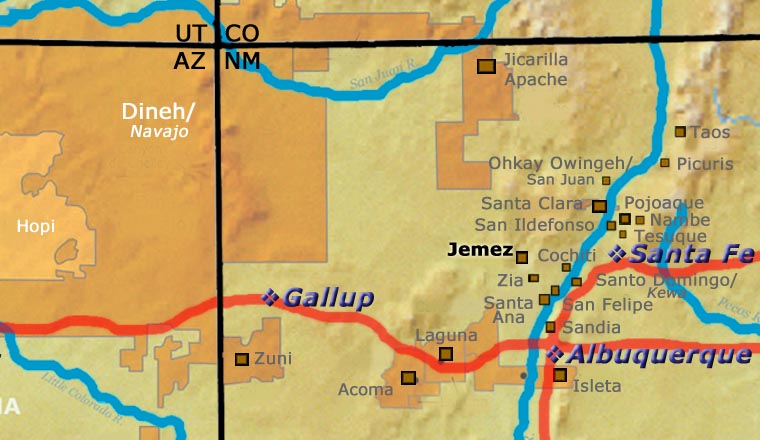

Dennis grew up at Jemez Pueblo but his father was from San Ildefonso, a distant relative of Maria Martinez.

Some Awards Earned by Dennis

- 1988 Gallup InterTribal Indian Ceremonial. Class. - Pottery, Div. - Bowl, plate, Second Place

- 1984 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. - Pottery, Cat. 1310 - Sgraffito style, First Place and Third Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class II - Pottery, Div. H - MIniatures, Third Place Class - Jewelry, Div. G - Nontraditional, new forms, First Place

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About the Mimbres Culture

The Mimbres culture existed in the Mimbres Valley of southern New Mexico from about 850 CE to about 1150 CE. They were a sub-culture of the greater Mogollon culture that extended from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre Mountains, north to the San Andres Mountains and northwest along the Mogollon Rim to the vicinity of today's Springerville, AZ.

North of the Gila Mountains was the influence of the Great Houses of the Chaco culture. Through comparisons of imagery and the colors used, it has been conjectured that Chaco was a more male dominant society while Mimbres was more female dominant. Both areas were settled, built, flowered and abandoned on almost exactly the same time schedules. But at the time of abandonment, the folks of Chaco mostly moved north while those of the Mimbres valley mostly went south.

The Mimbres people were among the first cultures that evolved their own forms of imagery and means of telling stories through those images. The Classic Mimbres period was the height of their creativity, from about 1000 CE to about 1150 CE. Then things changed and migrations began in earnest. Many moved south and brought some of their art to Paquimé. Others pushed north and then west, around the Gila Mountains. By 1200 CE the vast majority of the people in the area of the Mimbres Valley had moved elsewhere.

Most Mimbres pottery was black-on-white. Around 1120 CE there was an influx of migrants from Hohokam and Salado areas to the west. That's about when the first black-on-red pottery appeared in the Mimbres villages. Some of the imagery we see today from many of the Northern and Middle Rio Grande pueblos had its origins in the Mimbres Valley.

Substantial depopulation of the area occurred shortly after 1150 CE but there were many small surviving populations scattered around. Over time, these melted into the surrounding cultures with many families moving north to Acoma, Zuni and Hopi while others moved south to Casas Grande and Paquimé.

The greater Mogollon culture spanned the countryside from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre to Paquimé, then north through the Mimbres Valley to the edge of the White Sands and then northwest along the Mogollon Rim into east-central Arizona.

The time period from about 850 CE to about 1000 CE is classed the Late Basketmaker III period across the Southwest. The time period was characterized by the evolution of square and rectangular pithouses with plastered floors and walls. Ceremonial structures were generally dug deep into the ground. In the Mimbres Valley area, local forms of pottery have been classified as early Mimbres black-on-white (formerly Boldface Black-on-White), textured plainware and red-on-cream.

The Classic Mimbres phase (1000 CE to 1150 CE) was marked with the construction of larger buildings in clusters of communities around open plazas. Some constructions had up to 150 rooms. Most groupings of rooms included a ceremonial room, although smaller square or rectangular underground kivas with roof openings were also being used. Classic Mimbres settlements were located in areas with well-watered floodplains available, suitable for the growing of maize, squash and beans. The villages were limited in size by the ability of the local area to grow enough food to support the village.

Pottery produced in the Mimbres region is distinct in style and decoration. Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery was primarily decorated with bold geometric designs, although some early pieces show human and animal figures. Over time the rendering of figurative and geometric designs grew more refined, sophisticated and diverse, suggesting community prosperity and a rich ceremonial life. Classic Mimbres black-on-white pottery is also characterized by bold geometric shapes executed with refined brushwork and very fine linework. Designs may include figures of one or more humans, animals or other shapes, bounded by either geometric decorations or by simple rim bands. A common figure on a Mimbres pot is the turkey, others are the thunderbird, rabbit and various anthropomorphic, half-human figures. There are also a lot of different fish depicted, some are species found only in the Gulf of California (hundreds of miles away across the desert).

A lot of Mimbres bowls (with kill holes) have been found in archaeological excavations but most Mimbres pottery shows evidence it was actually used in day-to-day life and wasn't produced just for burial purposes.

There's a lot of speculation as to what happened to the Mimbres people as their countryside was rapidly depopulated after about 1150 CE. The people of Isleta, Acoma and Laguna find ancient Mimbres pot shards on their pueblo lands, indicating that pottery designs from the Mimbres River area migrated north. There are similar designs found on pot shards littering the ground around Casas Grandes and Paquimé near Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. Other than where they went, the only reasons offered for why they left involve at least small scale climate change. The usual comment is "drought" but drought could have been brought on by the eruption of a volcano on the other side of the planet, or a small change in the El Nino-La Nina schedule. Whatever it was that started the outflow of people, it began in the Mimbres River area and spread outward from there. Excavations in the eastern Mimbres region (nearer to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico) have shown that the people adapted to new circumstances and that adaptation itself moved them closer into alignment with surrounding villages and cultures. Eventually they just kind of merged into the background population.

The groups that moved south and built up Paquimé and Casas Grandes became powerful and wealthy over the next couple hundred years. Then they seem to have lost a war in the mid-1400s and the survivors were forced to migrate to the west, to a land a bit more hospitable for them at the time. It's also quite possible that they were defeated by volcanic eruptions on the other side of the planet: the 1100s, 1200s and 1300s were a time of migration in many parts of the world because of continuing bad weather events. The Little Ice Age that saw temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere drop as much as 2°C began in the early 1300s and lasted into the mid 1800s. NASA feels that this was mostly a result of large volumes of volcanic aerosols being pumped into the atmosphere at the time.