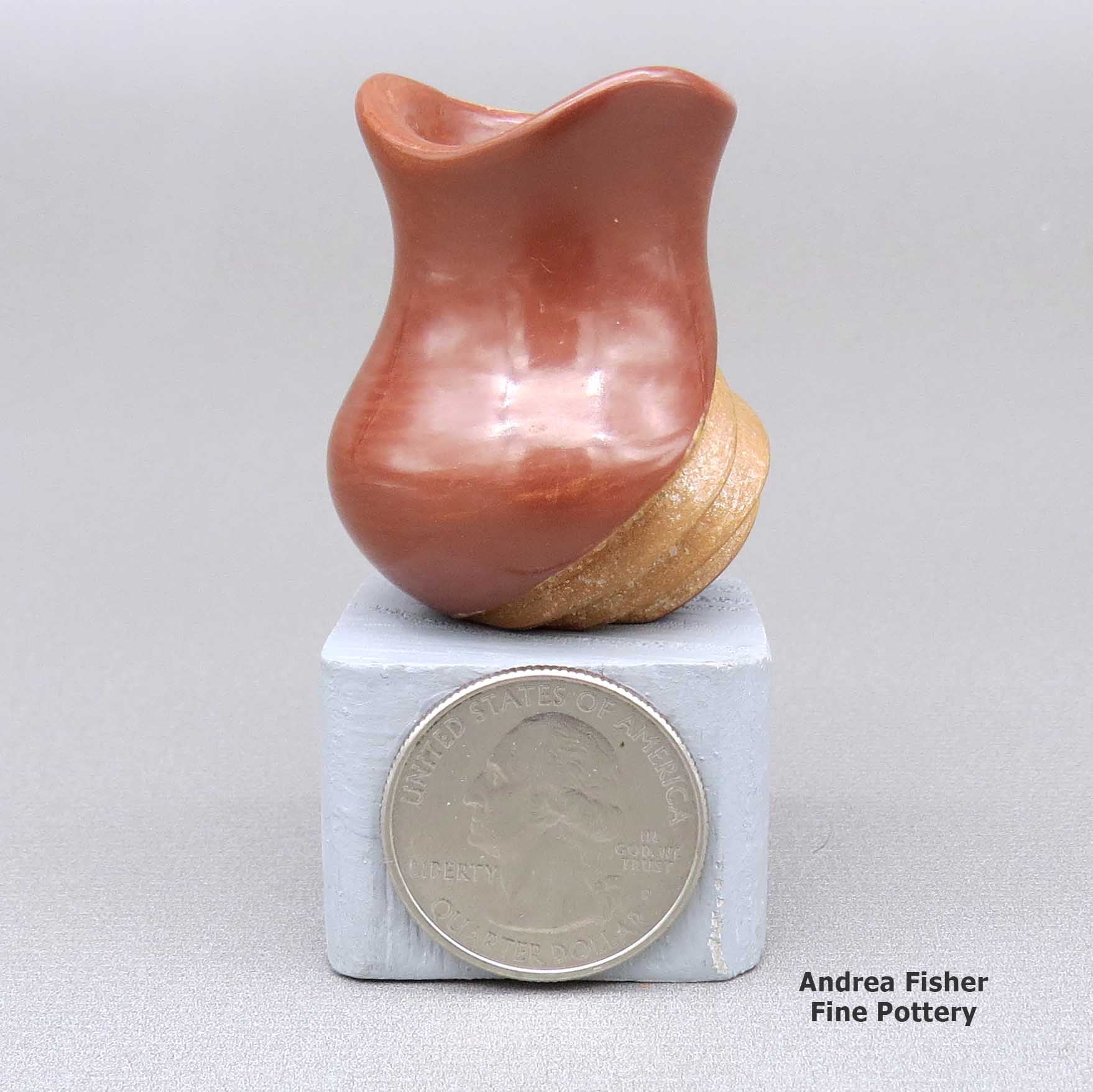

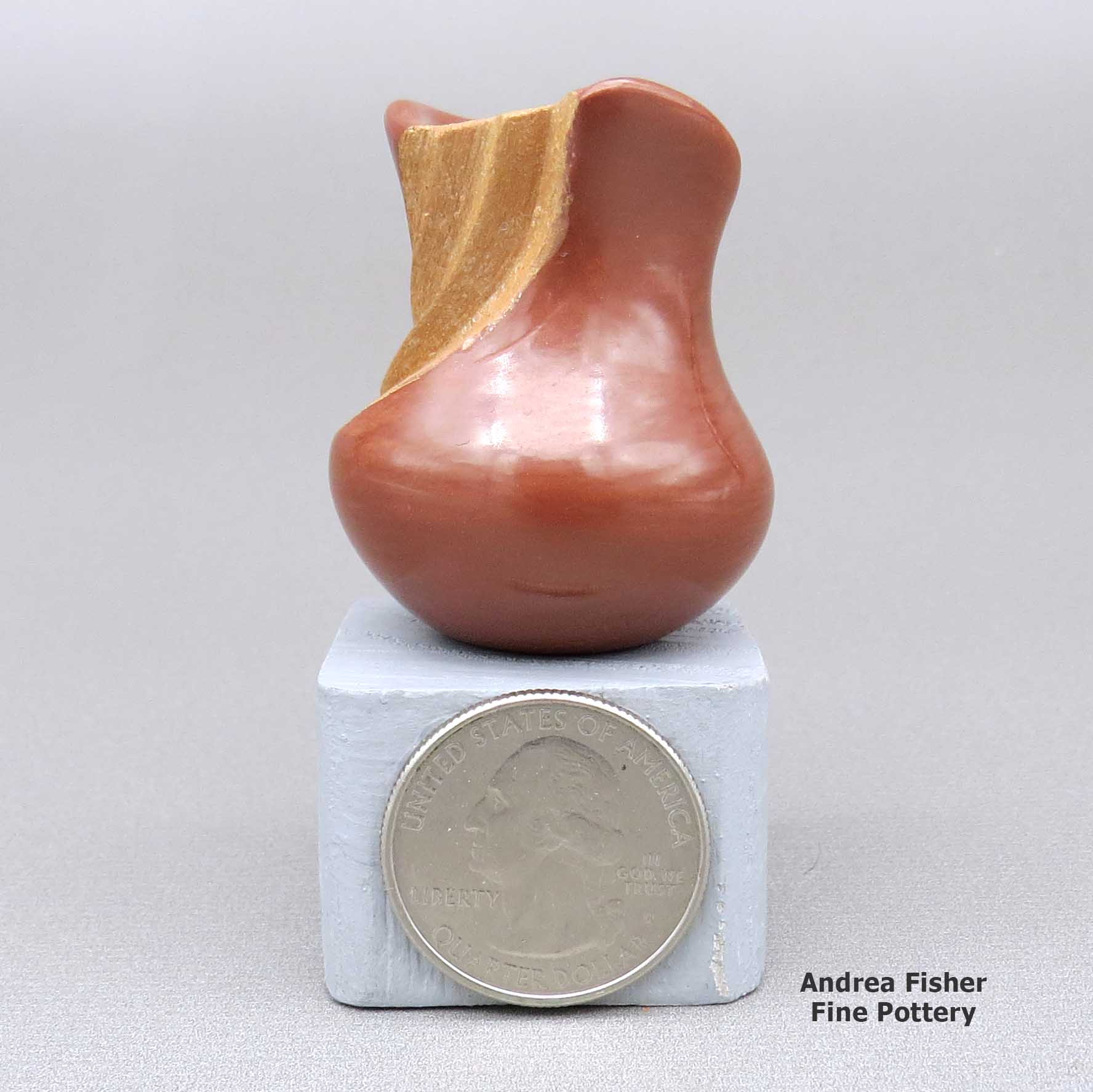

| Dimensions | 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | DT, with cornstalk hallmark |

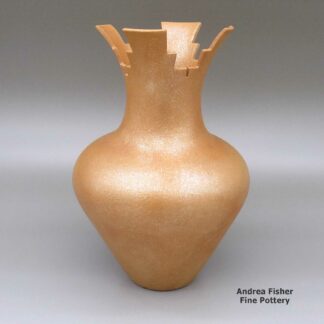

Dominique Toya, zzje3a191, Red jar with micaceous melon detail

$425.00

A miniature red jar with an organic opening and a carved micaceous gold melon swirl detail

In stock

Brand

Toya, Dominique

"The smaller the opening, the swirlier they get."

"The smaller the opening, the swirlier they get."Dominique Toya was born to Maxine Toya and Clarence Toya in 1971 at Jemez Pueblo. In those days she was known as Damian and she began creating pottery at about the age of five. She credits her mother Maxine for being the inspiration behind her interest in learning the traditional art. Her aunt, Laura Gachupin and grandmother, Marie G. Romero complete the roster of influential family potters in her early life.

Dominique gathers her clay and natural pigments from within the lands of Jemez Pueblo. Preparing the clay, she cleans and sifts and wets and mixes and dries, then hand coils, shapes, sands, and polishes before finally firing her pots.

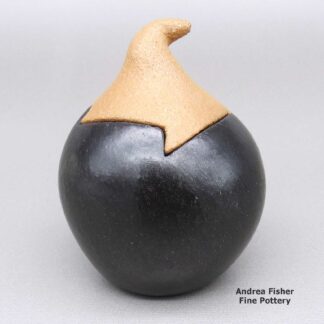

Dominique says she was inspired to create her signature swirl melon pots by well-known Santa Clara potter Nancy Youngblood. She is aiming for nothing short of perfection, from the shape of her pots to the swirls that pour out of her openings. "The smaller the opening," she said, "the swirlier they get." The lines that circle a Dominique jar are perfectly spaced by taking an ice pick and scratching through the clay one line at a time, eventually covering the pot from top to bottom. "It's all done by eyeball," she said. "It's just a part of me."

Later she will sandpaper the grooves deep into the pot. Those deep groves are another signature, as is the sparkle in the final micaceous slip. She signs her pots as: "Dominique Toya, Jemez", followed by the corn symbol to denote her clan origin.

Dominique's career shifted into high gear with an award in the pottery division at the 2000 Annual Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market. Then she was awarded Best of Class for Pottery at the 2009 Santa Fe Indian Market. A collaboration between Dominique and Jody Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo earned the duo the Best of Show award at the 2010 show at the Eiteljorg Museum of the American Indian in Indianapolis. She has been adding to her collection of blue ribbons almost every year since.

Career success, Dominique believes, is rooted in her decision to become "Dominique" and to leave behind an outer self that didn't fit her. Born "Damian", Dominique was already a successful potter before she accepted herself as a woman. She has been undergoing hormone therapy for the past several years as she completes her transformation. "My personal changes, my hormone therapy: everything happened all at once," she told us.

Dominique still tells us she gets her inspiration from her mother, her grandmother and from good friends Nancy Youngblood and Jody Naranjo. Her favorite shape to work with is the water jar, preferably carved with deep swirls and slipped with micaceous clay. As a 5th generation Jemez Pueblo potter she says clay is her life and it has allowed her to relax and enjoy this amazing and fulfilling journey through life.

Some Awards Dominique has earned

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Special Raw Material Award

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification IIA, Category 504 - Pins and Pendants, Second Place and an Honorable Mention

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 504 - Melon Bowls and Melon Jars, formed or carved: Honorable Mention

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Painted, native clay, hand build, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for collaborative artwork with Maxine Toya. Awarded for artwork: Traditional Storage Jar

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, including ribbed, native clay, hand build, fired out-of-doors: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Swirled Mica Water Jar

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional Painted Pottery. Category 604 - Painted polychrome pottery in the style of Jemez, Zia, Santa Ana, Sandia, San Felipe, Isleta, any form: Second Place shared with Maxine Toya

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional burnished black or red ware, incised, painted or carved, Category 704 - Incised or carved, any form: Second Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 504 - Melon Bowls and Melon Jars, Formed or Carved: Second Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional Painted Pottery, Category 604 - Painted polychrome pottery in the style of Jemez, Zia, Santa Ana, Sandia, San Felipe, Isleta, any form: First Place. Shared First Place with Maxine Toya

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 504 - Melon bowls and melon jars, formed or carved: Honorable Mention

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, Native Clay, Hand Built, Unpainted Including Ribbed: First Place

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Judge's Choice Award - - Della C. Warrior. Awarded for artwork: Storage Jar

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Judge's Choice Award - Kathleen L. Howard. Awarded for artwork: Storage Jar

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted including ribbed: Honorable Mention

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted: Honorable Mention shared with Maxine Toya

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Eiteljorg Museum Indian Market: Best of Show, collaborative work with Jody Naranjo. Awarded for artwork: "Double Insanity"

- 2010 Eiteljorg Museum Indian Market, Division 5 - Pottery, Category 501 - Traditional: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Swirled Vase

- 2010 Eiteljorg Museum Indian Market, Division 5 - Pottery, Category 502 - Contemporary: First Place for collaborative work with Jody Naranjo. Awarded for artwork: "Double Insanity"

- 2010 Eiteljorg Museum Indian Market, Division 5 - Pottery, Category 504 - Miscellaneous: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Pride"

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted, including ribbed: Second Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice Award - Helen Kersting. Shared with Jody Naranjo. Awarded for artwork: "Double Insanity"

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Classification II - Pottery: Best of Class

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted: First Place

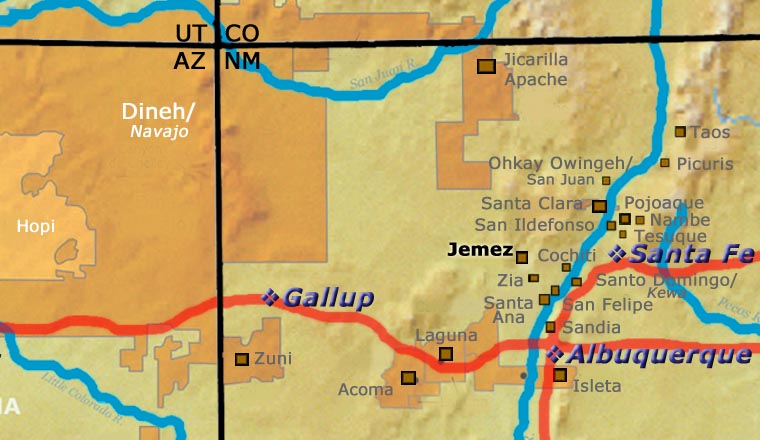

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Jars

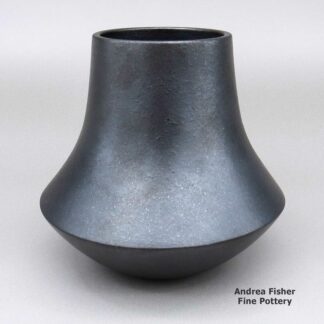

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

Benigna Medina Madelena Family Tree - Jemez Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

Benigna Medina was born and raised at Zia Pueblo, learning to make pottery the Zia way as she grew up. Then she married Ramon Madelena from Jemez Pueblo and moved to his home there. She infused the Jemez potters of the time with Zia methods, forms and designs, strengthening a very weak Jemez tradition: the Spanish had virtually destroyed all Jemez traditions 200 years before and recovery was very hard.

- Benigna Medina Madelena (c.1880-) & Ramon Madelena

- Persingula M. Gachupin (ca. 1910-1994) & Joe R. Gachupin

- Marie G. Romero (1927-)

- Laura Gachupin (1954-)

- Benina Foley (1982-)

- Gordon Foley (1975-)

- Maxine Toya (1948-)

- Dominique Toya (1971-)

- Mariam Toya (1974-)

- Laura Gachupin (1954-)

- Leonora G. Fragua (1938-)

- Matthew Fragua (1963-)

- Virginia Ponca Fragua (1961-) & M. Pecos

- Brandon Pecos Fragua (1993-)

- Bertha Gachupin (1954-)

- Antonia Gachupin (1970s-) & Albert Yepa

- Kajzia Gachupin (1991-)

- Kiana Gachupin (1993-)

- Okoya Gachupin

- Antonia Gachupin (1970s-) & Albert Yepa

- Marie G. Romero (1927-)

- Elcira Madelena (c.1915-)

- Mary Rose Toya

- Eloise Toya

- Norma Toya

- Mary Rose Toya

- Josephita Madelena

- Reyes Marie Madelena-Butler (1938-)

- Shannon Madelena-Ellington

- Reyes Marie Madelena-Butler (1938-)