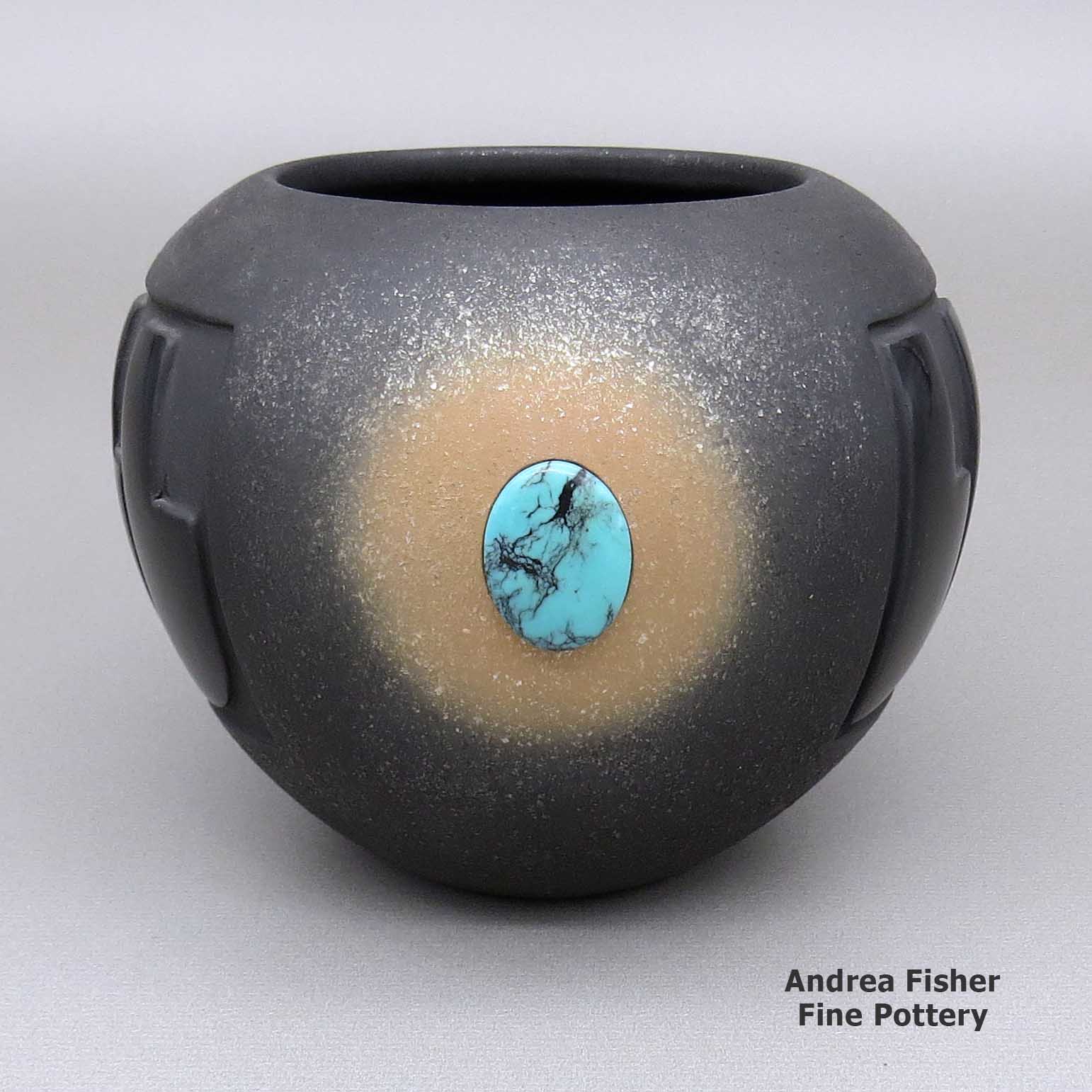

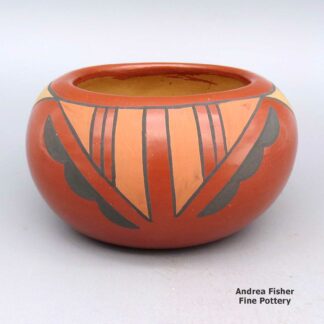

| Dimensions | 4.75 × 4.75 × 4 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, adhesive residue on bottom |

| Signature | Dora of San Ildefonso |

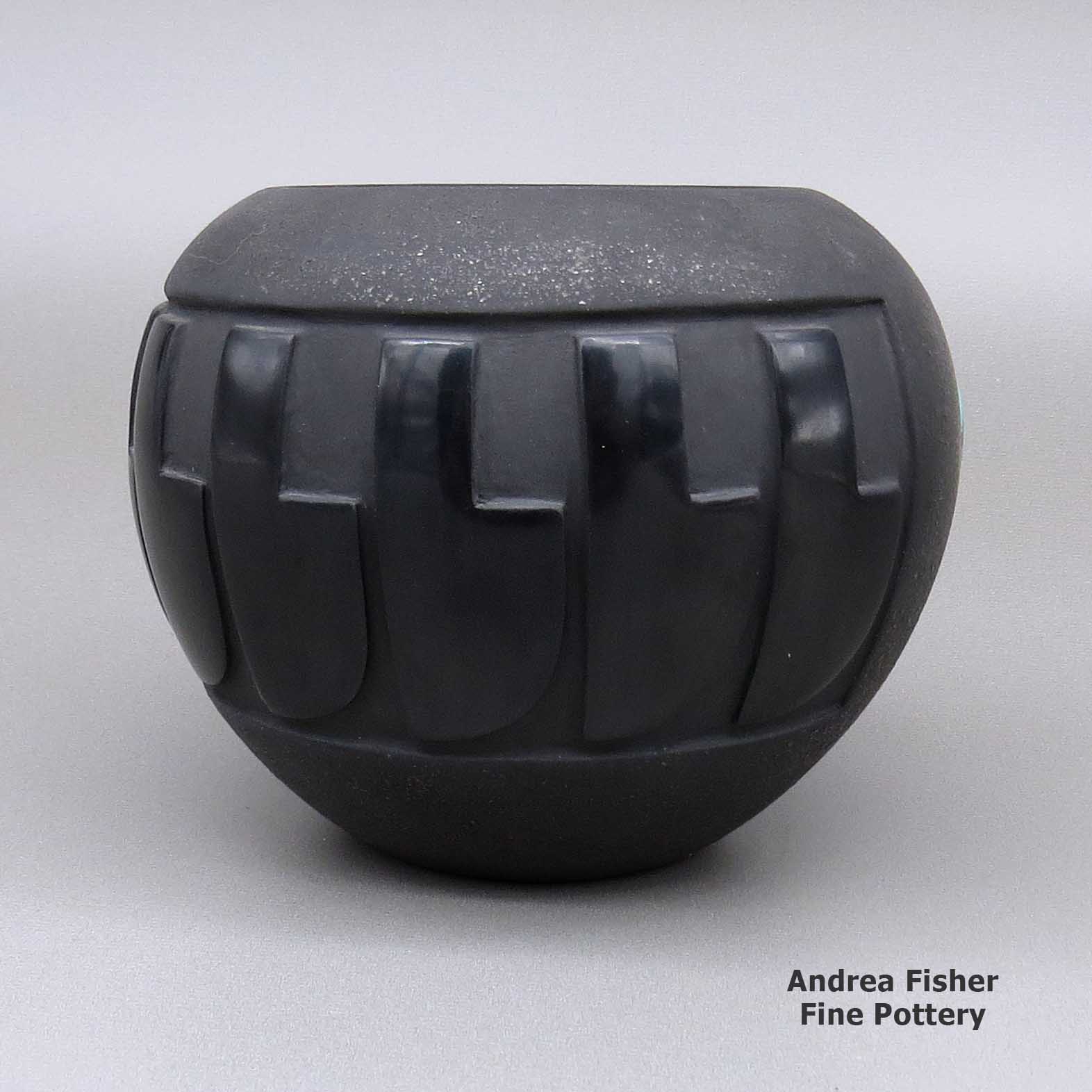

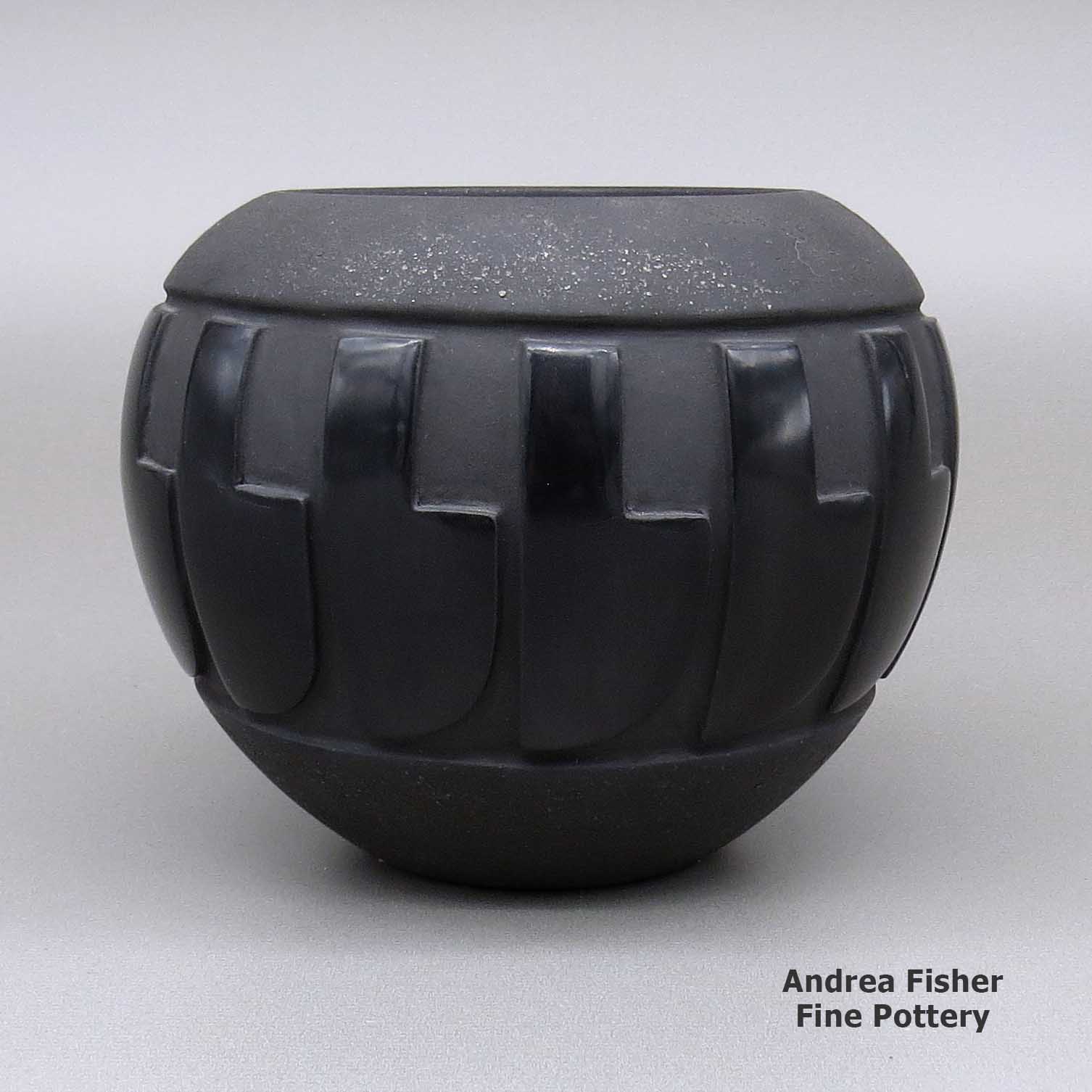

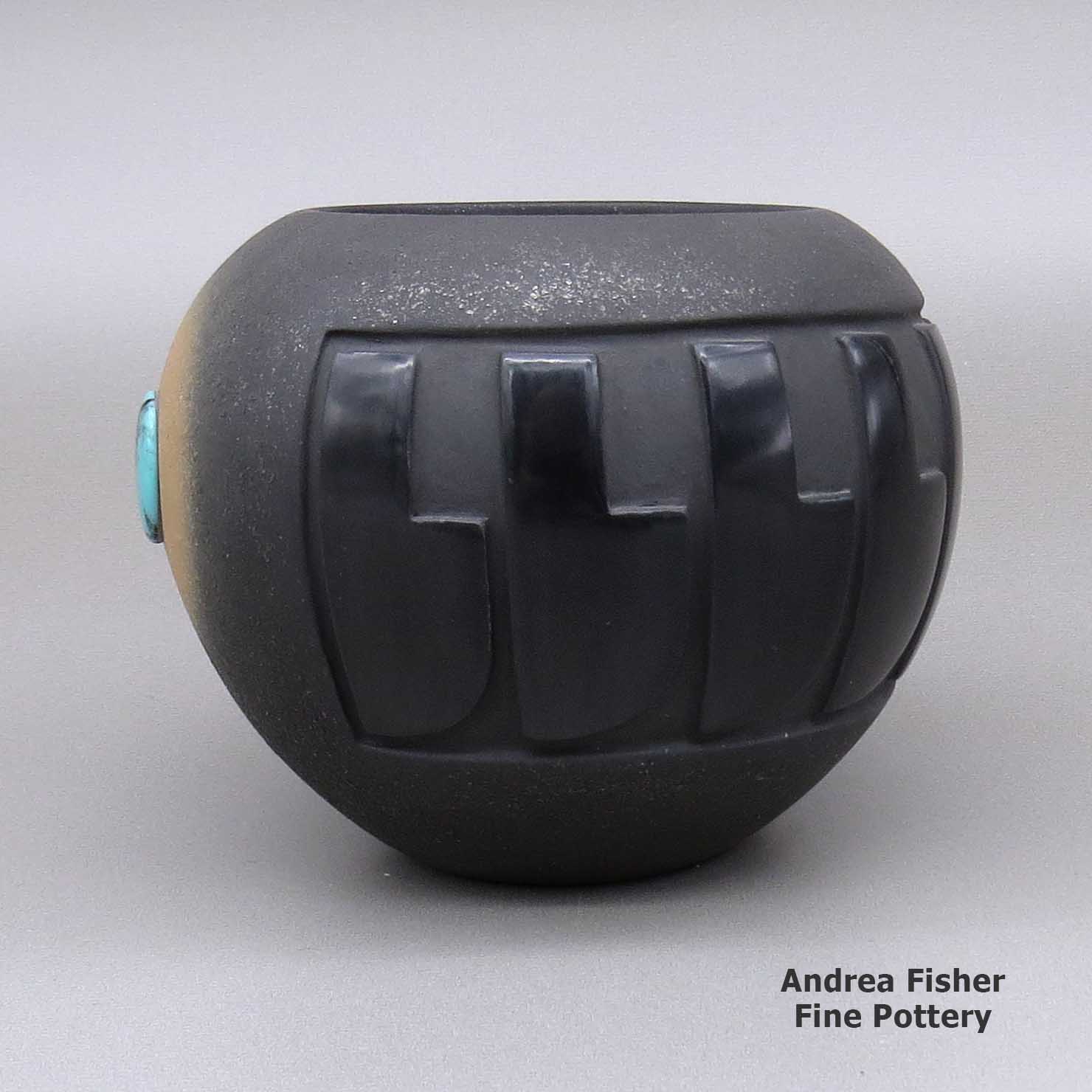

Dora Tse Pe, spsi3c060, Micaceous bowl with a lightly carved and painted ring-of-feathers geometric design

$1,250.00

A micaceous black bowl with a sienna spot, a lightly carved and polished ring-of-feathers geometric design and an inlaid turquoise detail

In stock

Brand

Tse Pe, Dora

Dora Gachupin was born into Zia Pueblo in 1939 to parents Candelaria Medina of Zia Pueblo and Tony Gachupin of Jemez Pueblo. She married Johnnie "Tse-Pe" Gonzales of San Ildefonso Pueblo in 1961 and, contrary to the ancient tradition, she moved to his home from Zia (the Pueblo people are generally matrilineal: home is usually where the wife's family is).

Dora had grown up learning the Zia pottery designs and shapes but she was also used to Zia clay and using crushed basalt as a tempering agent. At San Ildefonso, Dora was exposed to the highly polished red and black wares that Rose Gonzales, her mother-in-law (of San Juan lineage), was making. The clay, the slips and the tempering agents were quite different. "We didn't polish at Zia", Dora has said, "we used slips and plant and mineral paints." It was from Rose that she learned polishing, carving and other San Ildefonso and San Juan styles and techniques.

Other exceptional potters who have influenced Dora over the years include Popovi Da with his two-tone black and sienna ware and Tony Da with his exquisite sgraffito work and his use of stone inlays.

Dora’s work often includes turquoise, coral or onyx inlays on pots that also include combinations of black and sienna with micaceous slips. Her innovative style has sometimes been called "contemporary" and she often works with both polished clay and dull or micaceous clays in the same piece. However, she says she doesn't like that "contemporary" term and considers herself and her work to be traditional.

She earned many awards over the years, including Best in Traditional Pottery and Master Potter at Santa Fe Indian Market. Dora believes in quality not quantity and sees her art to be a gift from God. "It gives me pleasure to create beauty from the earth," she says. "Also to know that long after I've served my time on this earth, the pots I've created will live on."

Some Exhibits that featured Dora's work

- Choices and Change: American Indian Artists in the Southwest. Heard Museum North Scottsdale. Opened June 30, 2007

- Recent Acquisitions from the Herman and Claire Bloom Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ January 11, 1997 - July 31, 1997

- Fifth Annual Hollywood Premiere. Four Seasons Hotel, Los Angeles, CA. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, AZ. November 23, 1991 - November 24, 1991

- Magic in Clay. Morrill Hall, University of Nebraska State Museum. Lincoln, NE. May 5, 1991 - August 30, 1991

- 1976 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. November 26 - December 5, 1976

Some Awards Dora earned

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice Award

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Class. II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Judge's Choice Award

- 1976 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Pottery, Division C - Figurines, bells, jewelry, miniatures, etc.: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Miniature vase

- 1976 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Pottery, Division C - Figurines, bells, jewelry, miniatures, etc.: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Turtle with etched serpent

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

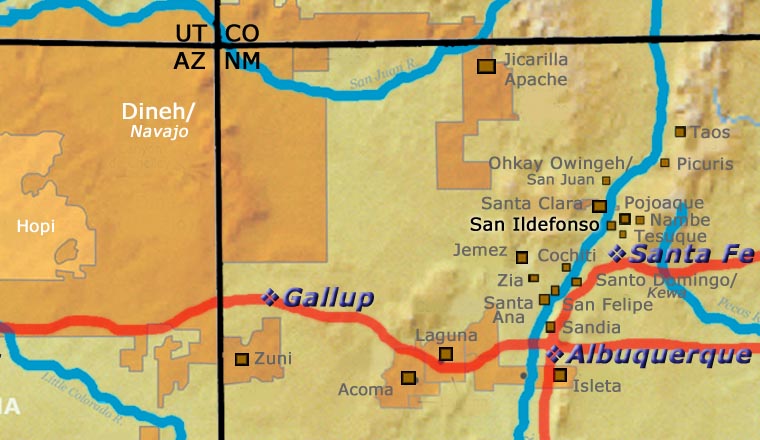

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Bowls

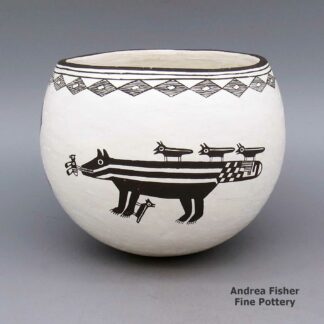

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

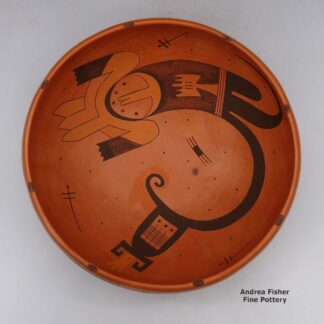

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.

Ramona Gonzales Family Tree - San Ildefonso Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Ramona Sanchez Gonzales (1885-), second wife of Juan Gonzales (painter)

- Rose (Cata) Gonzales (daughter-in-law)(1900-1989)(San Juan) & Robert Gonzales (1900-1935)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Andrea Tse Pe (1975-)

- Candace Tse-Pe (1968-)

- Gerri Tse-Pe (1963-)

- Irene Tse-Pe (1961-)

- Jennifer Tse-Pe (1966-1983)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (1940-2000) & Jennifer Tse Pe (Sisneros - second wife, Santa Clara)

- Marie Gonzales-Kailahi & James Kailahi

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Blue Corn (Crucita Gonzales Calabaza)(1921-1999)(step-daughter of Ramona) & Santiago Calabaza (Santo Domingo) (d. 1972)

- Heishi Flower (Diane Calabaza-Jenkins) (1955-)

- Joseph Calabaza (Tha Mo Thay)

- Elliott Calabaza

- Lucille Calabaza-King

- Nancy Calabaza

- Sophia Calabaza

- Stacey Calabaza

- Krieg Kalavaza

- Vera Solomon (Laguna)

Rose' students: - Juanita Gonzales (1909-1988) & Louis Wo-Peen Gonzales (brother of Rose Gonzales husband)

- Adelphia Martinez (1935- )

- Lorenzo Gonzales (1922-1995)(adopted by Louis & Juanita) & Delores Naquayoma (Hopi/Winnebago)

- Jeanne M. Gonzales (1959-)

- John Gonzales (1955-)

- Laurencita Gonzales

- Linda Gonzales

- Marie Ann Gonzales

- Raymond Gonzales

- Robert Gonzales (1947-) & Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-)

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Oqwa Pi (Abel Sanchez)(1899-1971) & Tomasena Cata Sanchez (Rose' sister) (1903-1985)

- Skipped generation

- Russell Sanchez (1966-)

- Skipped generation