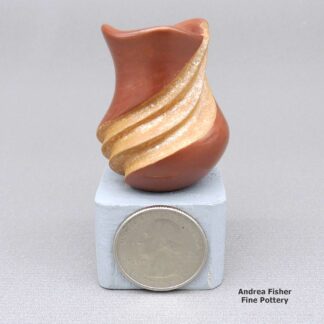

| Dimensions | 2.75 × 2.75 × 3.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Glenn Gomez Taos Pojoaque |

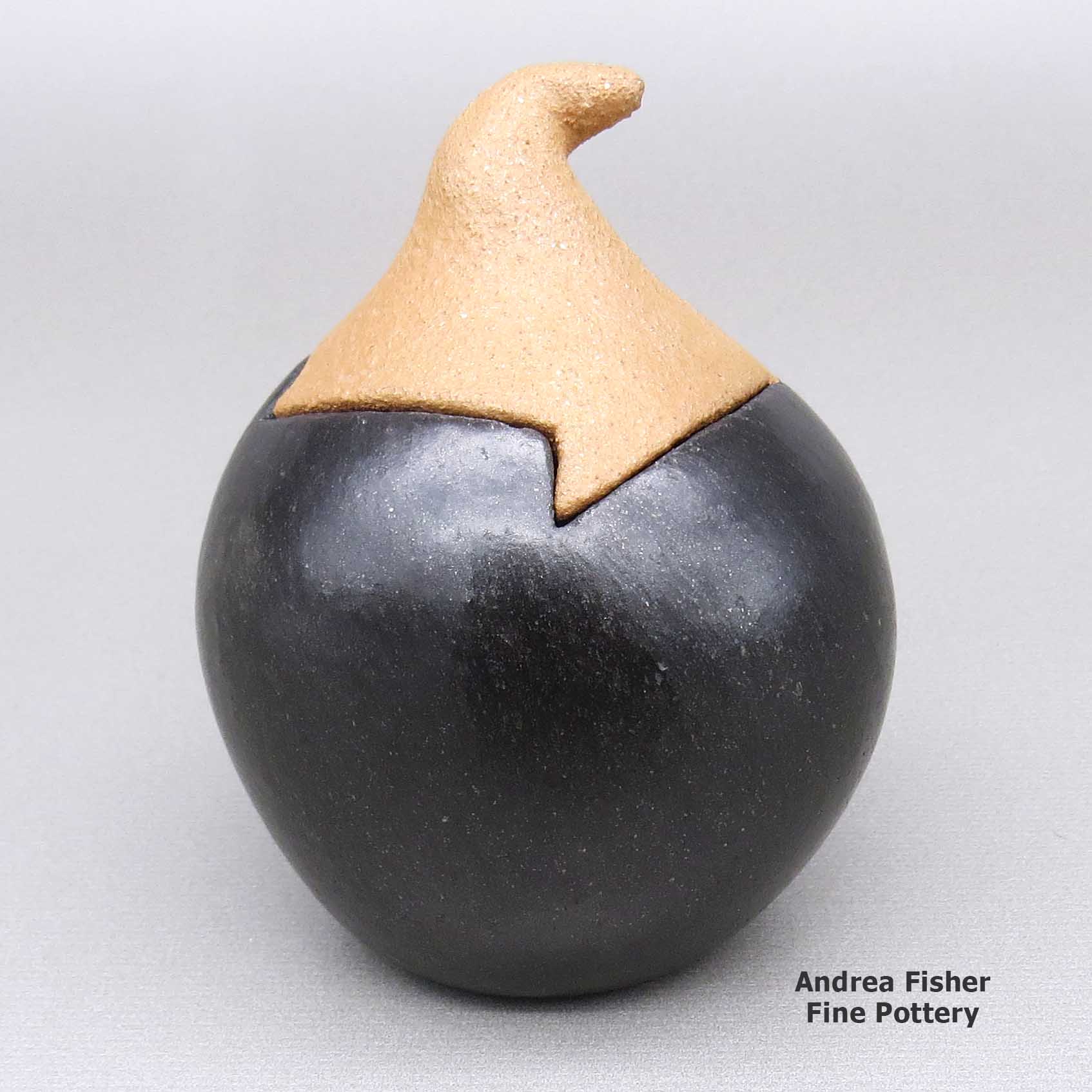

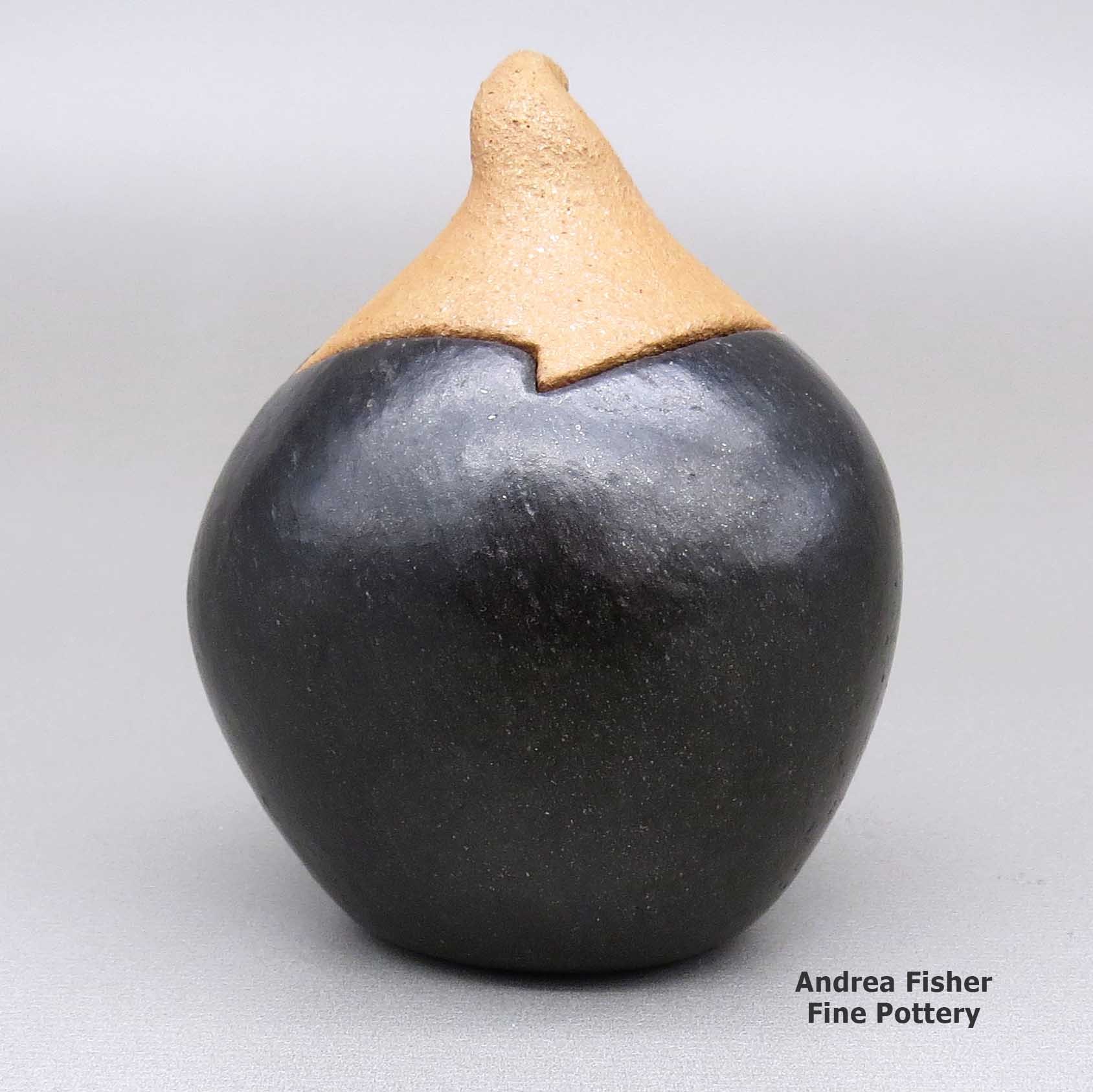

Glenn Gomez, zzta3b190, Black gourd-shaped lidded jar with golden micaceous lid

$395.00

A black gourd-shaped lidded jar, with a micaceous gold lid

In stock

Brand

Gomez, Glenn

Cordelia Feliciana Viarrial Gomez was the last surviving member of the group that returned in the 1930s to rebuild Pojoaque Pueblo (she died in 2017 at the age of 88). Her grandfather was José Antonio Tapia, the pueblo governor who had left in 1908 in search of work after smallpox, drought and incursions by Anglo settlers had devastated the pueblo. They returned when the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the Indian Re-Organization Act of 1933 called for all tribal members to return and form a tribal council or risk having their lands confiscated and their tribe decertified.

The people returned to a setting with no indoor plumbing, no running water, no electricity and no natural gas. Cordi lived through the upgrading of the pueblo, the building of schools and the establishment of modern business enterprises. Through those years she worked as a potter, seamstress, teacher and cook.

In 1988, her son, Glenn Gomez, was working on a road crew for the summer and looking at the soil they were digging in. He was admiring the colors of the dirt and the flecks of mica all through it. He finally asked his mother if that clay was what she used to make her pots. She pulled off a lump of her working clay and broke it in half. She handed Glenn one half and told him to "make something with it, something that is made in your own style."

Glenn did, and he was enthralled with working with clay. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts from 1989-1992 and earned an Associates of Fine Arts degree. In 1993 he became the "Artist in the Museum" at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe.

Glenn produced micaceous pottery: bowls, jars, canteens and figures. One of his chicken figure canteens is in the collection of the Poeh Museum at Pojoaque Pueblo.

A Short History of Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo consists of two main structures, both of which are counted among the oldest continuously inhabited structures in the United States. The location straddles the Rio Pueblo de Taos (also known as Red Willow Creek), whose headwaters rise in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The pueblo was designated a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960 and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

The Taos people first figure in the archaeological record about the same time Pot Creek Pueblo burned and was abandoned in the early 1300s. Some of the residents of Pot Creek split from the others and moved northeast to join with and merge into a small Tanoan pueblo located in a perfect spot with a great view. That became today's Taos Pueblo. The native tongue today at Taos Pueblo is Northern Tiwa, a member of the Tanoan family of languages. It is felt the tribe migrated to the area during the time of the Great Drought in the Four Corners region, the same drought that essentially forced nearly all the Pueblo peoples to migrate to the Rio Grande, Rio Puerco or Little Colorado River areas. The people of Taos, though, also feel that some of their people came from the north, which would include possible Jicarilla Apache migrants, and some from the far south, preferably from Aztec or Mesoamerican lands.

On the other hand, Taos was mostly peopled by 7 Jicarilla Apache clans and 6 Tewa clans, in addition to the one or two Tanoan clans left from before the immigrants arrived. For hundreds of years the semi-nomadic Jicarillas came and went from the forests and mountains around Taos, moving with the seasons. They established settlements in the Tusas Mountains and along the Upper Rio Grande. The economies and families of Taos and the Jicarillas were intertwined. Pottery and other trade goods from the region of Taos Pueblo have been found in Dismal River culture sites in eastern Colorado and across Kansas to the Black Hills of South Dakota. The pueblo served as a central contact point between the Rio Grande Pueblos to the south and the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Apache and Ute to the north, northwest and northeast.

Around 1620 a Jesuit priest oversaw the construction of the first mission of San Geronimo de Taos. Friction between the tribe and the Spanish led to the killing of the resident priest and destruction of the church in 1660. Priests returned and rebuilt the church only to have the church destroyed again and two resident priests killed in the beginning hours of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

The Spanish were evicted from northern Nuevo Mexico in 1680 but returned in force in 1692. By 1700, a third mission church was being built at Taos Pueblo. For a few years the tribe and the Spanish got along, forced to be amicable in order to deal with their common enemies: the Ute and Comanche tribes. That pressure was relieved in 1776 when Governor Juan Bautista de Anza and his troops killed virtually the entire upper hierarchy of the Comanche tribe in the Battle of Cuerno Verde, near Greenhorn Mountain in southern Colorado.

In the 1700s an annual trade fair was established, promoted by the Spanish. The Spanish also established a slave market on Taos Plaza where captive Native Americans and black slaves were actively sold until Juneteenth Day in 1867. Taos Pueblo became a neutral zone where fighting and raiding were banned for the duration of the fair. The trade fairs continued after Mexico declared its independence in 1820, with a bit more tax and danger added (Mexico couldn't protect anyone from the regularly marauding Comanches, Apaches, Utes and Kiowas).

That's also when American fur trappers and traders first appeared in the area. The American military arrived in 1847, at the beginning of the Mexican-American War. Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West had been waiting at Bents Old Fort on the Arkansas River in Colorado. As soon as the declaration of war happened, they flooded into New Mexico and took the territory without firing a shot. They replaced a few politicians, then they kept going. The American presence quickly led to the Taos Rebellion. The Taos Rebellion saw Governor Charles Bent and several other prominent Americans in the non-Indian village of Taos killed immediately. A few days later American troops and armed citizens arrived from Santa Fe and, thinking the rebels had taken refuge in the San Geronimo de Taos church, they bombarded the church, destroying it and killing many innocent women and children who were hiding inside. That effectively ended the rebellion. After a short trial, 17 of the surviving rebels were hanged from trees surrounding the plaza in the village of Taos.

A new mission church was constructed around 1850 near the west gate of the pueblo wall but the ruins of the old church are still visible today.

One result of the Taos Rebellion is that the tribe has never signed a peace treaty with the United States Government. That led to President Theodore Roosevelt using an Executive Proclamation to remove some 48,000 acres of the pueblo's mountain land and combine that with the fledgling Carson National Forest in 1906. That land was a point of major contention between the pueblo and Congress until it was returned to the tribe by President Richard M. Nixon in 1970. An additional 764 acres was returned to the tribe in 1996.

Today the community of Taos Pueblo is considered one of the most private, secretive and conservative of all the pueblos, even though the Pueblo of Taos offers more shops for visitors than any other pueblo. The North and South Houses of the pueblo are now a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Elisa Rolle, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

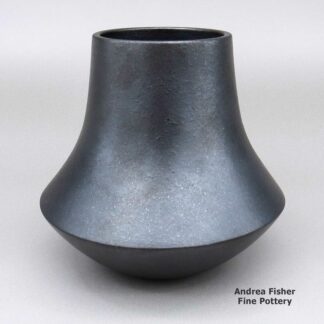

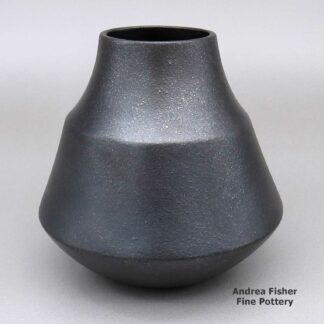

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

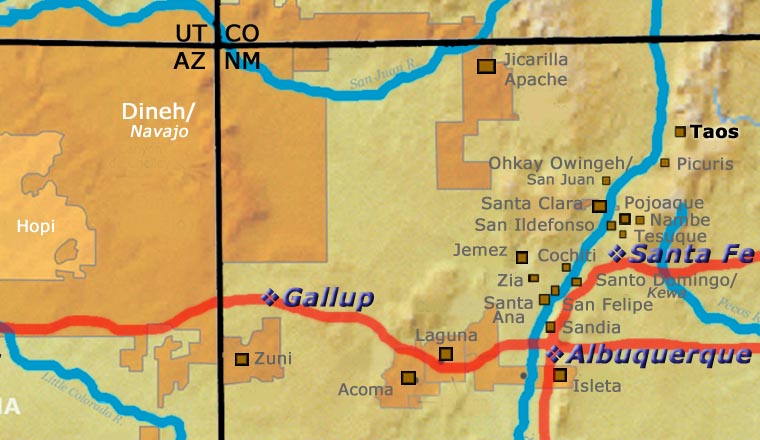

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.