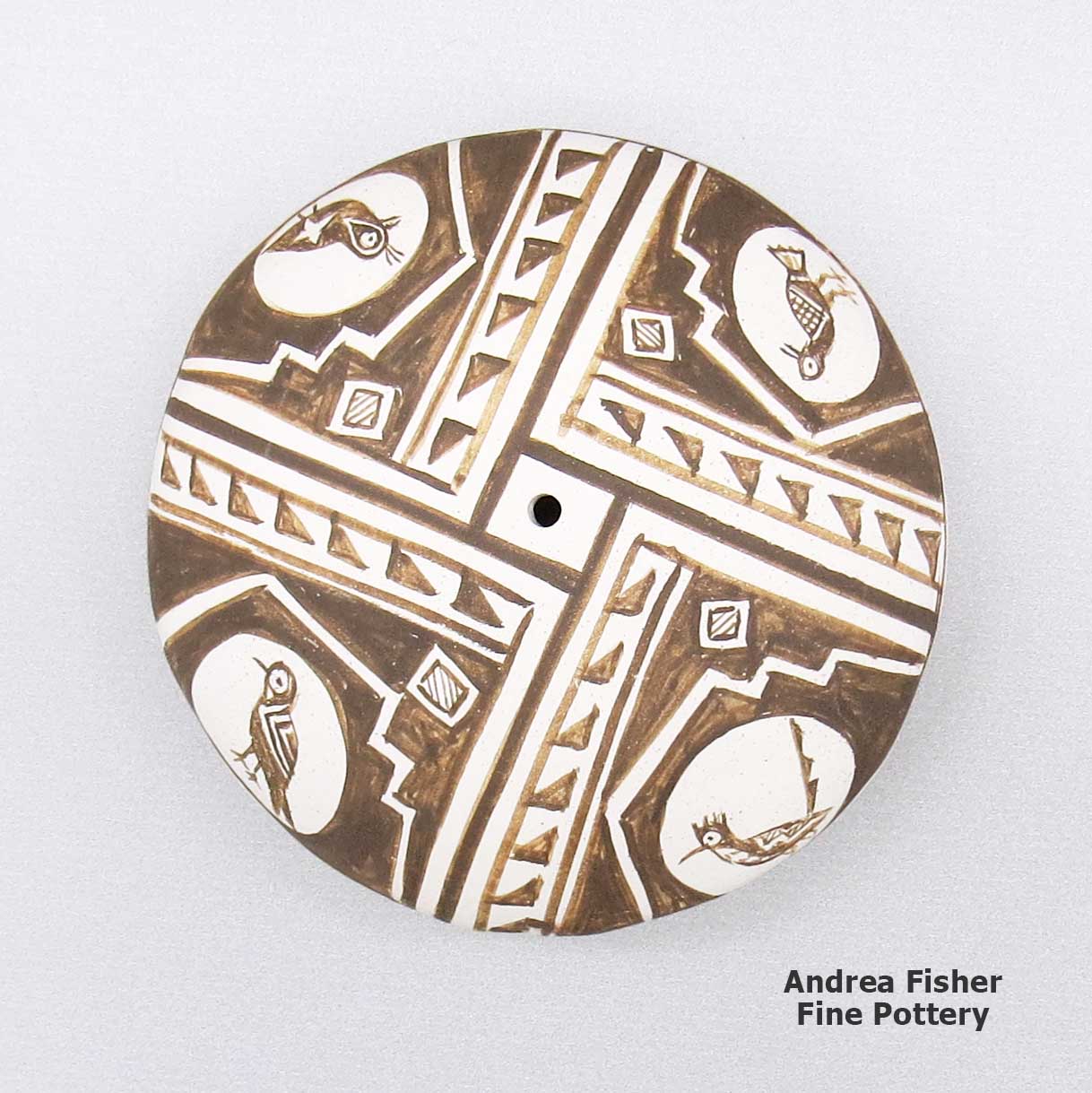

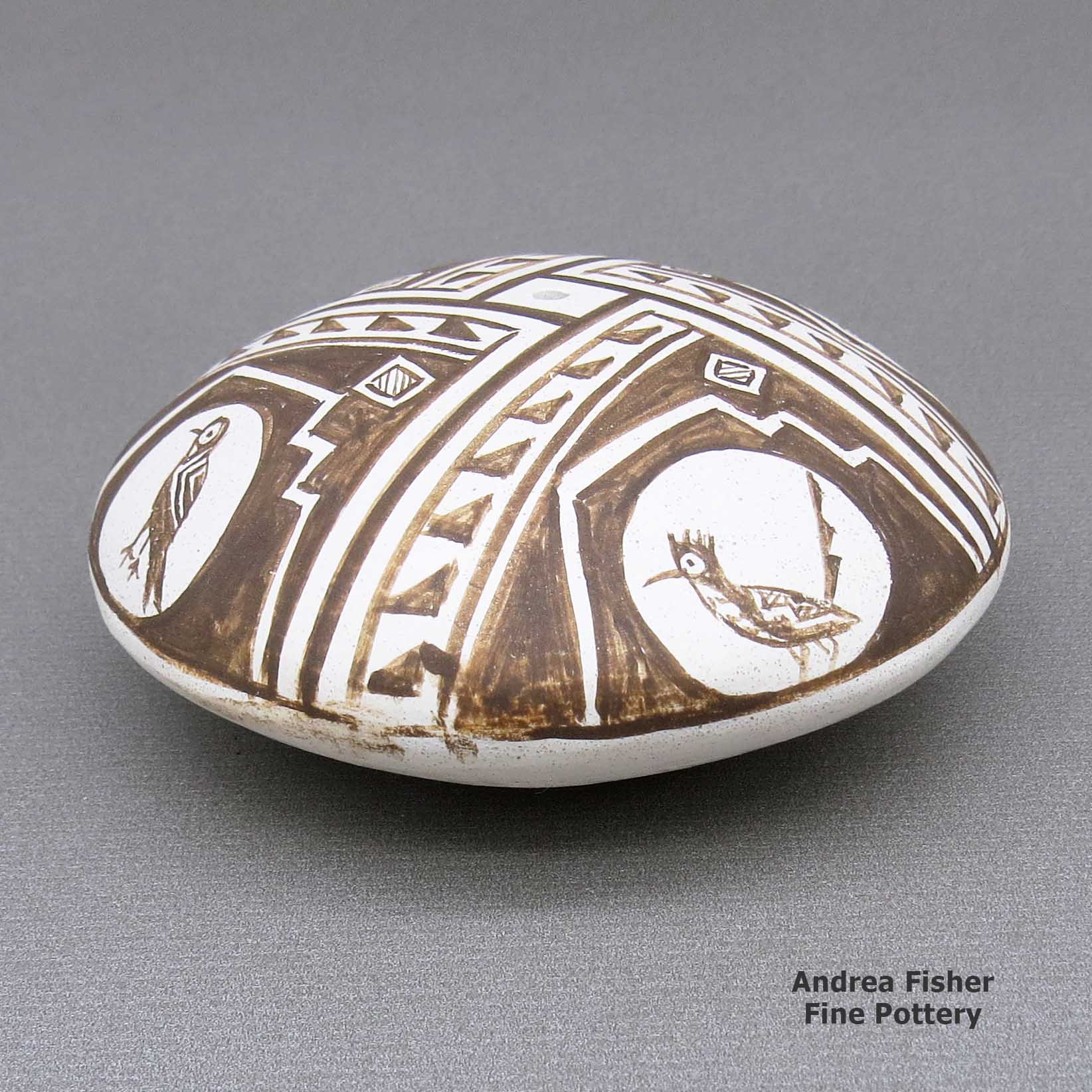

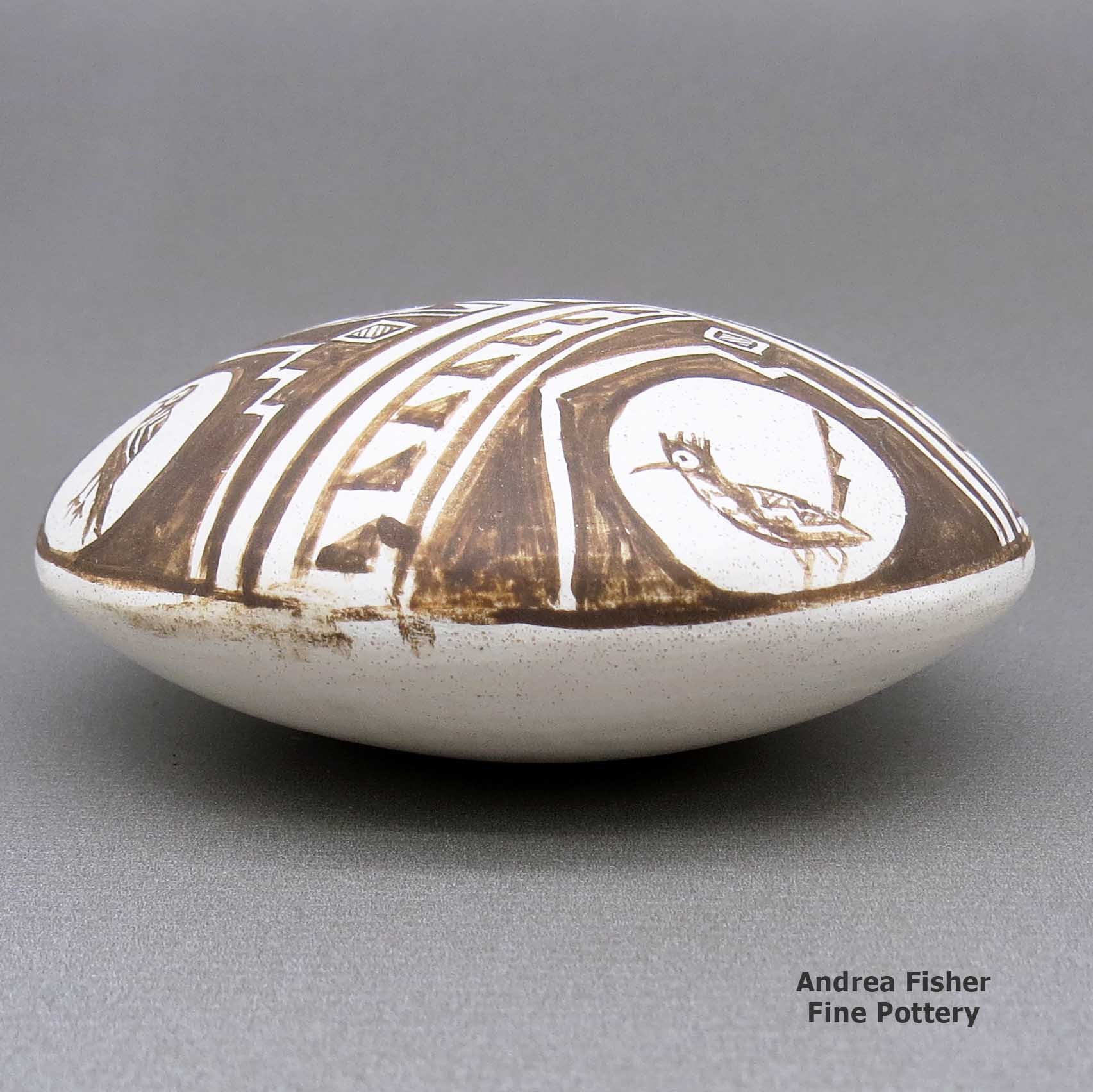

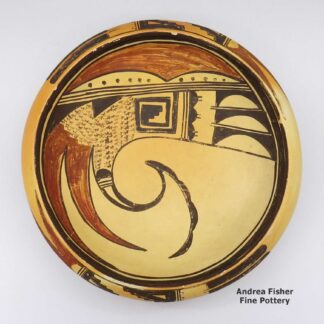

| Dimensions | 3 × 3 × 1.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Isleta W/T KD, with hallmarks |

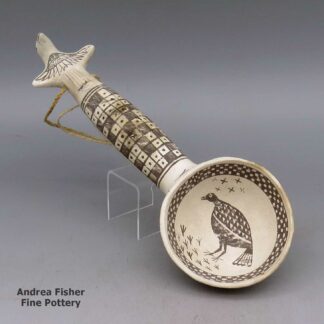

Kimo DeCora, zzle3b280m4, Black and white seed pot with a Mimbres quail, roadrunner, bird and geometric design

$225.00

A black-on-white seed pot decorated with a Mimbres quail, roadrunner, bird and geometric design

In stock

Brand

DeCora, Kimo

After finishing high school, Kimo attended Haskell Indian Nations University and studied off-set lithography. He became a certified off-set pressman, then ten years later he got interested in painting. At first he drew his inspiration from his love of the outdoors. Then he started to connect with ancient Anasazi and Mimbres ruins and some of the artifacts he found there.

He learned the basics of traditional pottery making on his own but he also learned through watching Cipriano Romero Medina and John Montoya at work.

Kimo's favorite shapes to make are bowls, jars, small owls and his trademark miniatures. Over the years his pieces have earned him many blue ribbons at the Winnebago, NE, Fine Arts Show (18 ribbons in 1983 alone!), more blue ribbons at the Albuquerque CeramicFest and even more blue ribbons at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery's annual Best of the Best Shows.

Kimo told us his inspiration comes from his pre-Columbian ancestors, specifically the people from the Mimbres Valley in southern New Mexico. It's their designs he most often uses to decorate his work. His signature reflects his tribal affiliation (W/T: Winnebago Ho-Chunk / Isleta-Tiwa), along with some subconscious doodling for a hallmark.

The Winnebago/Ho-Chunk were never prolific creators of pottery but they have been known to paint and do fancy beadwork. Kimo doesn't do beadwork but he does craft and paint Christmas ornaments and miniature pots and figures. He also creates paintings in traditional Pueblo and nouveau-Western Pueblo styles. Kimo told us he practices Tai Chi before he does any painting as it enhances his brushwork and helps him to be more creative and productive.

In Kimo's words: "I'm not the extrovert type and, like many others, don't need to be noticed to be happy ('Call me Hieronymous, cuz I like being anonymous'). It's a blessing to enjoy good health and be appreciated for the medium I express myself with. I also believe humor is a good thing."

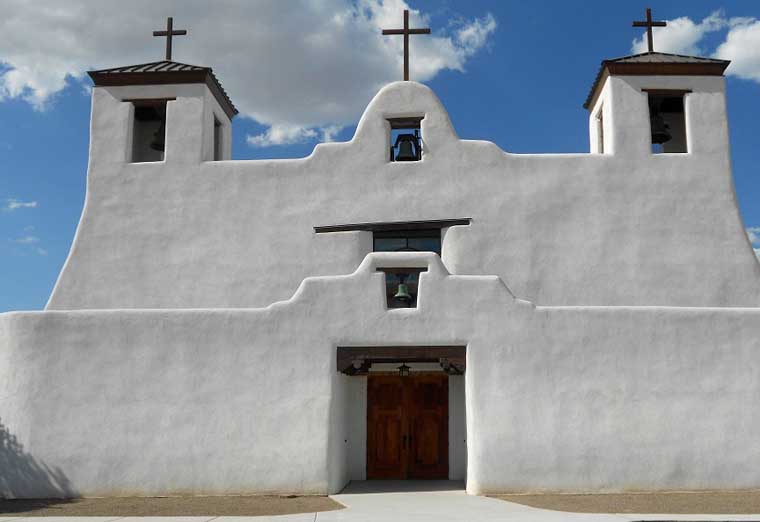

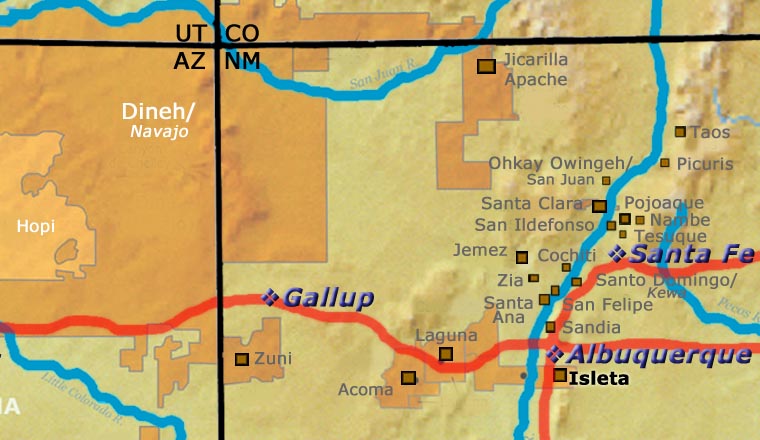

A Short History of Isleta Pueblo

Isleta Pueblo was founded in the 1300s. Archaeologists have put forth various ideas as to where the people came from with some scholars saying they migrated north from Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the south while others say they migrated southeastward from either Chaco Canyon in the 1100s and 1200s or from the Four Corners area in the 1200s and 1300s. There is every possibility they are an indigenous Tano population that was merged with Aztec migrants coming north from central Mexico and they were never part of the Chacoan world. Their Tiwa language is shared with nearby Sandia Pueblo and a very similar tongue is spoken to the north at Taos and Picuris Pueblos. The two dialects are sometimes referred to as Southern and Northern Tiwa. The Taos people also consider that some of their ancestors migrated north from Aztec lands long ago while others came from the north.

When the Spanish arrived in the area they named the pueblo "Isleta" (meaning: island). The residents were relatively accommodating to the Spanish priests when compared to the reception the same priests got in other areas of Nuevo Mexico (making Isleta something of an "island of safety" for the Spanish in an ocean of hostility). When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, Isleta either couldn't or wouldn't participate in the rebellion.

When the Spanish governor was evicted from Santa Fe he went to Albuquerque, then to Isleta and gathered his troops. With warriors from the northern pueblos harassing their every move, none of the Spaniards wanted to go back and fight so when they left Isleta and headed south, many Isletans went south to the El Paso area with them. Those who went south were allowed to establish their own pueblo at Ysleta del Sur, a place that at the time was beyond the boundaries of the village of El Paso.

Other Isletans fled to the Hopi settlements in Arizona and returned after the fighting was clearly over, many with Hopi spouses. When the Spanish returned in 1682 they found the Isleta mission church burned and the main structure was being used as a livestock pen. When Don Diego de Vargas came in 1692 with troops intent on reconquering New Mexico, they found the whole village of Isleta empty and burned.

The governor ordered the pueblo be rebuilt and resettled so residents were brought in from Taos and Picuris to the north and from Ysleta del Sur to the south. By 1720 a new, more grandiose mission had been built on the foundations of the first.

Over the next century some dissident members of the Laguna and Acoma Pueblo communities migrated to Isleta. While they were welcomed into the main Isleta pueblo at first, friction developed over the years until in the late 1800s, the small communities of Oraibi and Chicale were established. Most of the newcomers moved to one or the other but some returned to Acoma and Laguna.

For more info:

Pueblo of Isleta at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Isleta official website

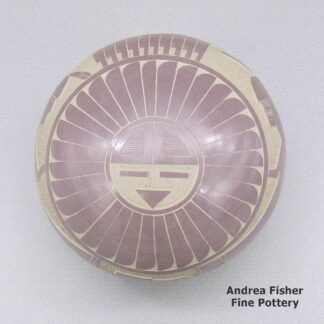

About the Seed Pot

It was a matter of survival to the ancient Native American people that seeds be stored properly until the next planting season. Small, hollow pots were made to ensure that the precious seeds would be kept safe from moisture, light, bugs, reptiles and rodents.

After seeds were put into the pot, the small hole in the pot was plugged. The following spring the plug was removed and the seeds were shaken from the pot directly onto the planting area.

Today, seed pots are no longer necessary due to readily available seeds from commercial suppliers. However, seed pots continue to be made as beautiful, decorative works of art.

The sizes and shapes of seed pots have evolved and vary greatly, depending on the vision of Clay Mother as developed through the artist. The decorations vary, too, from undecorated white, buff or red seed pots to multi-colored painted, carved, applique and sgraffito designs, sometimes with inlaid gemstones, micaceous clay and silver or clay lids.

Because of the multitude of shapes and sizes, the name "seed pot" is generally reserved for pieces with tiny openings.

About the Mimbres Culture

The Mimbres culture existed in the Mimbres Valley of southern New Mexico from about 850 CE to about 1150 CE. They were a sub-culture of the greater Mogollon culture that extended from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre Mountains, north to the San Andres Mountains and northwest along the Mogollon Rim to the vicinity of today's Springerville, AZ.

North of the Gila Mountains was the influence of the Great Houses of the Chaco culture. Through comparisons of imagery and the colors used, it has been conjectured that Chaco was a more male dominant society while Mimbres was more female dominant. Both areas were settled, built, flowered and abandoned on almost exactly the same time schedules. But at the time of abandonment, the folks of Chaco mostly moved north while those of the Mimbres valley mostly went south.

The Mimbres people were among the first cultures that evolved their own forms of imagery and means of telling stories through those images. The Classic Mimbres period was the height of their creativity, from about 1000 CE to about 1150 CE. Then things changed and migrations began in earnest. Many moved south and brought some of their art to Paquimé. Others pushed north and then west, around the Gila Mountains. By 1200 CE the vast majority of the people in the area of the Mimbres Valley had moved elsewhere.

Most Mimbres pottery was black-on-white. Around 1120 CE there was an influx of migrants from Hohokam and Salado areas to the west. That's about when the first black-on-red pottery appeared in the Mimbres villages. Some of the imagery we see today from many of the Northern and Middle Rio Grande pueblos had its origins in the Mimbres Valley.

Substantial depopulation of the area occurred shortly after 1150 CE but there were many small surviving populations scattered around. Over time, these melted into the surrounding cultures with many families moving north to Acoma, Zuni and Hopi while others moved south to Casas Grande and Paquimé.

The greater Mogollon culture spanned the countryside from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre to Paquimé, then north through the Mimbres Valley to the edge of the White Sands and then northwest along the Mogollon Rim into east-central Arizona.

The time period from about 850 CE to about 1000 CE is classed the Late Basketmaker III period across the Southwest. The time period was characterized by the evolution of square and rectangular pithouses with plastered floors and walls. Ceremonial structures were generally dug deep into the ground. In the Mimbres Valley area, local forms of pottery have been classified as early Mimbres black-on-white (formerly Boldface Black-on-White), textured plainware and red-on-cream.

The Classic Mimbres phase (1000 CE to 1150 CE) was marked with the construction of larger buildings in clusters of communities around open plazas. Some constructions had up to 150 rooms. Most groupings of rooms included a ceremonial room, although smaller square or rectangular underground kivas with roof openings were also being used. Classic Mimbres settlements were located in areas with well-watered floodplains available, suitable for the growing of maize, squash and beans. The villages were limited in size by the ability of the local area to grow enough food to support the village.

Pottery produced in the Mimbres region is distinct in style and decoration. Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery was primarily decorated with bold geometric designs, although some early pieces show human and animal figures. Over time the rendering of figurative and geometric designs grew more refined, sophisticated and diverse, suggesting community prosperity and a rich ceremonial life. Classic Mimbres black-on-white pottery is also characterized by bold geometric shapes executed with refined brushwork and very fine linework. Designs may include figures of one or more humans, animals or other shapes, bounded by either geometric decorations or by simple rim bands. A common figure on a Mimbres pot is the turkey, others are the thunderbird, rabbit and various anthropomorphic, half-human figures. There are also a lot of different fish depicted, some are species found only in the Gulf of California (hundreds of miles away across the desert).

A lot of Mimbres bowls (with kill holes) have been found in archaeological excavations but most Mimbres pottery shows evidence it was actually used in day-to-day life and wasn't produced just for burial purposes.

There's a lot of speculation as to what happened to the Mimbres people as their countryside was rapidly depopulated after about 1150 CE. The people of Isleta, Acoma and Laguna find ancient Mimbres pot shards on their pueblo lands, indicating that pottery designs from the Mimbres River area migrated north. There are similar designs found on pot shards littering the ground around Casas Grandes and Paquimé near Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. Other than where they went, the only reasons offered for why they left involve at least small scale climate change. The usual comment is "drought" but drought could have been brought on by the eruption of a volcano on the other side of the planet, or a small change in the El Nino-La Nina schedule. Whatever it was that started the outflow of people, it began in the Mimbres River area and spread outward from there. Excavations in the eastern Mimbres region (nearer to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico) have shown that the people adapted to new circumstances and that adaptation itself moved them closer into alignment with surrounding villages and cultures. Eventually they just kind of merged into the background population.

The groups that moved south and built up Paquimé and Casas Grandes became powerful and wealthy over the next couple hundred years. Then they seem to have lost a war in the mid-1400s and the survivors were forced to migrate to the west, to a land a bit more hospitable for them at the time. It's also quite possible that they were defeated by volcanic eruptions on the other side of the planet: the 1100s, 1200s and 1300s were a time of migration in many parts of the world because of continuing bad weather events. The Little Ice Age that saw temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere drop as much as 2°C began in the early 1300s and lasted into the mid 1800s. NASA feels that this was mostly a result of large volumes of volcanic aerosols being pumped into the atmosphere at the time.