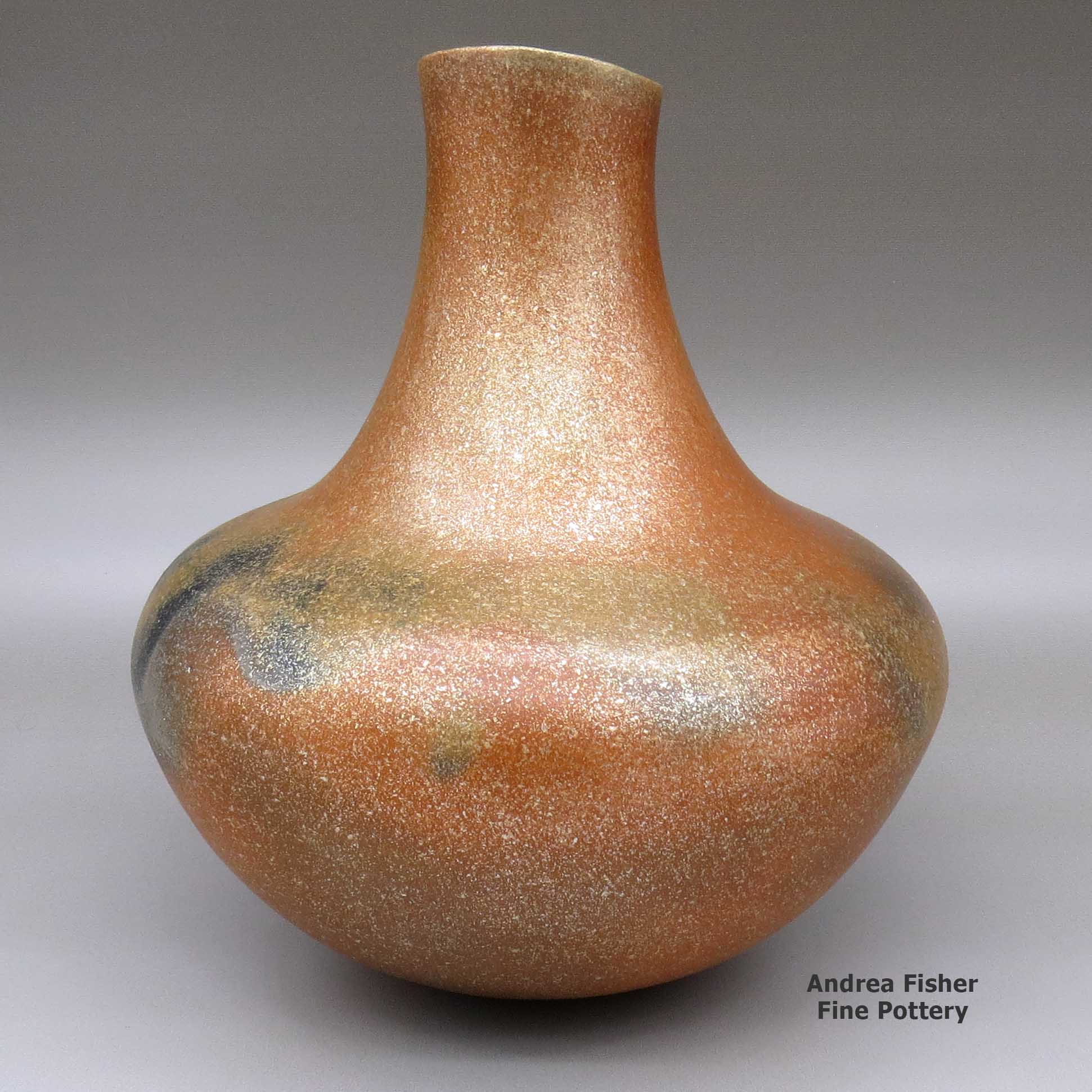

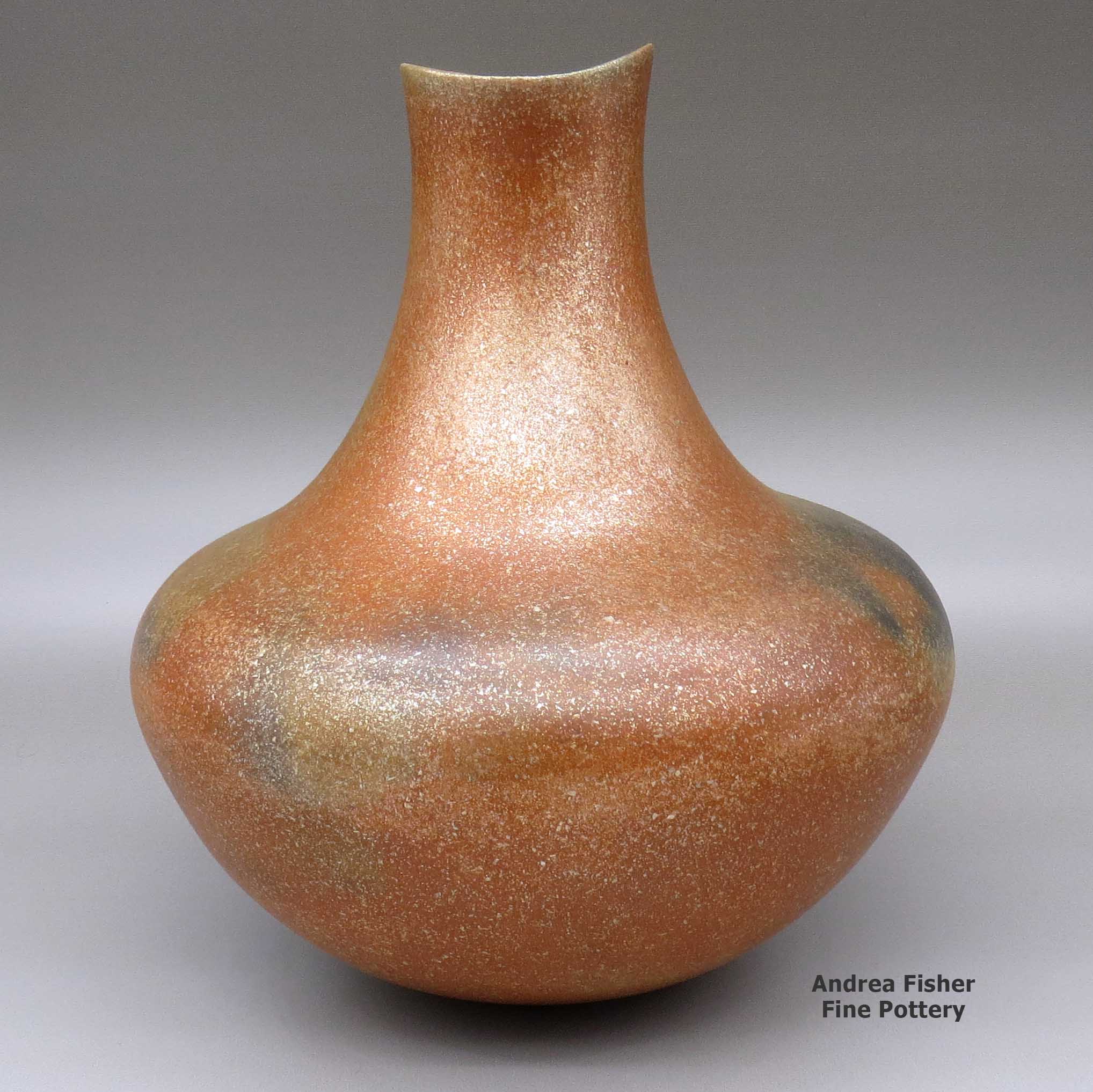

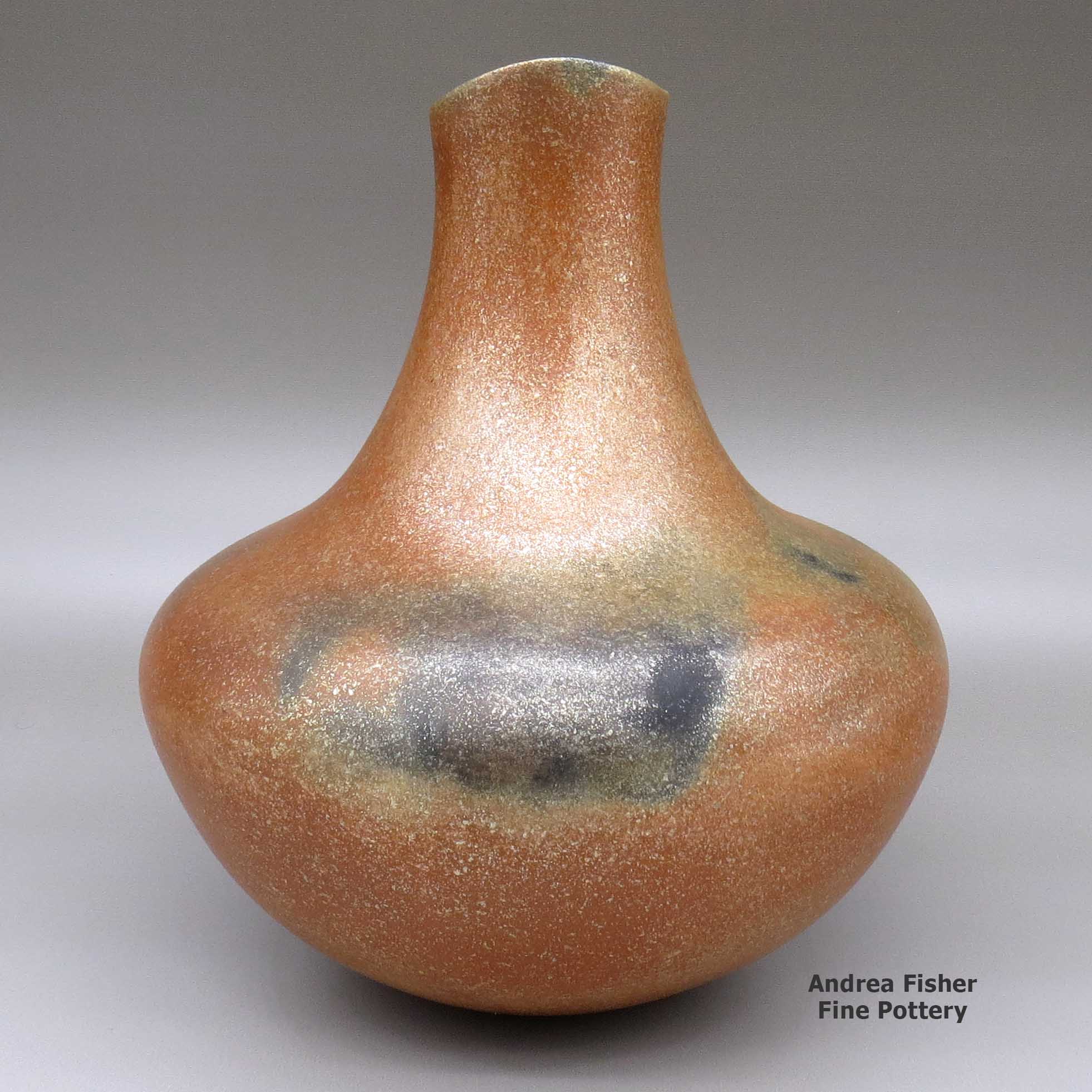

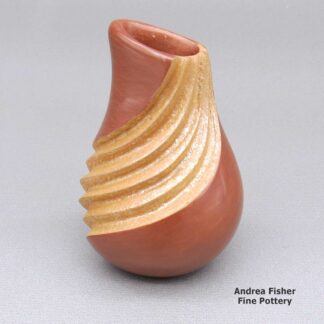

| Dimensions | 7.5 × 7.5 × 4.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, normal wear |

| Signature | Vigil Nambe |

Lonnie Vigil, rcna3d196, Golden micaceous jar with fire clouds

$4,900.00

A golden micaceous jar with a long neck, an organic opening and fire clouds

In stock

Brand

Vigil, Lonnie

Born in May 1949, Lonnie Vigil said he had no conscious desire to become an artist when he was growing up at Nambe Pueblo. Instead, he finished high school and went on to earn a degree in business administration from Eastern New Mexico University. Then he pursued a career as a financial and business consultant, first at the Eight Northern Pueblos office in New Mexico and then at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.

By the early 1980s, he was becoming aware that his work and life in Washington "gave me nothing to feed my soul." A performance at the Kennedy Center called Night of the First Americans inspired him to return to Nambé.

At first he spent days wandering the pueblo lands and praying, seeking a vision to follow into his future. He discovered a source of micaceous clay on pueblo land, then he found polishing stones in the ruins of his grandparents' home. That's when he got his first inkling that the rest of his life would be "committed to the Clay Mother."

In the beginning, it was hard because there was no one to teach him. "I prayed for direction from the Clay Mother and slowly the information began to come," he says. "I also asked for the help of my great-grandmother and my great-aunts, who were all potters. And I still ask their guidance today."

Apparently he was guided into re-creating Nambé Pueblo's famous micaceous clay pottery. But Nambé potters used to use micaceous clay to seal their pots for use in cooking and storage while Lonnie has elevated the use of micaceous clay to the state of a fine art.

He practiced working with micaceous clay until one day in 1994 he was declared the first recipient of the Ron and Susan Dubin Native American Artist Fellowship at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe. Upon receiving the fellowship, Lonnie said, "I am honored to be the first Dubin Fellow at such a fine institution as the School for Advanced Research. The Fellowship is an affirmation of the work I am doing." That support allowed him to take the time to study the ancient micaceous pottery in their collections.

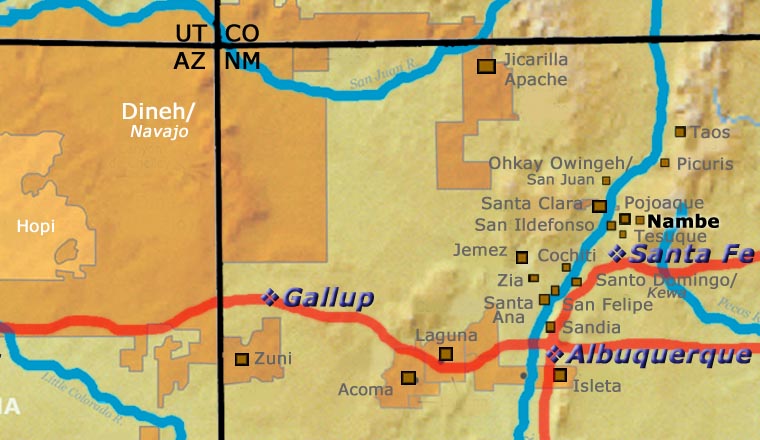

Micaceous pottery is distinguished by the sparkling mica flecks naturally distributed in the clay. Historically, micaceous pottery was used for cooking and storage by the people of Nambé, Picuris, Taos and the Jicarilla Apache. Overlooked by many collectors in the past, Lonnie Vigil has been characterized as single-handedly reviving unpainted micaceous clay pottery and establishing it as a contemporary art form.

Lonnie's signature large pots have earned the top awards at several Santa Fe Indian Markets (including the Best of Show ribbon in 2001) and he was honored with the Native Treasures 2010 Living Treasure Award. He sees himself as "a guardian of the clay" and says, "I feel responsible for making sure that the Clay Mother stays alive in my village."

Working with the School for Advanced Research, Lonnie helped to organize the first Micaceous Pottery Symposium and Market in Santa Fe in 1995. His work is shown in museums around the world, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Indian Arts Research Center, the Smithsonian Institute and the Horniman Museum in London, England. His work is also found in many private collections, including that of his holiness, the Dalai Lama.

Some of the Exhibits that have Featured Lonnie's work

- Something Old, Something New, Nothing Borrowed: New Acquisitions from the Heard Museum Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. April 2, 2011 - March 18, 2012

- Gifts of the Spirit, Works by Nineteenth-Century and Contemporary Native American Artists. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, Massachusetts. November 15, 1996 - May 18, 1997

- Fifth Annual Hollywood Premier. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, Arizona. November 23-24, 1991. Note: held at the Four Seasons Hotel, Los Angeles, California

About Nambé Pueblo

Nambé Pueblo was settled in the early 1300s when a group of Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) made their way from what is now the Bandelier National Monument area closer to the Rio Grande in search of more reliable water sources and more arable land.

At first they settled mostly high in the mountains, coming down to the river valleys in the summer to grow crops. Eventually, they felt safe enough to stay in the valleys and slowly abandoned the high mountain villages.

When the Spanish first arrived, Nambé was a primary economic, cultural and religious center for the area. That attracted a large Spanish presence and the nature of that presence caused the Nambé people to join wholeheartedly in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 to throw out the Spanish oppressors.

When the Spanish returned in 1692, their rule was significantly less harsh. However, the Spanish brought horses into the New World and as the number of Spanish increased, so did the number of horses. That brought more and more raids from the Comanches as they came for horses and whatever else they could carry away. The Comanches were finally subdued by Governor Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776 but by then, the impact of European diseases was being strongly felt. A smallpox epidemic in the late 1820s virtually ended the making of pottery at Nambé.

Photo courtesy of John Phelan, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Tewa Design Sources

The Northern Tewa people are mostly from the villages of Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Nambé and Tesuque. The Hopi-Tewa of Arizona are descendants of the Southern Tewa. The Tewa share a common heritage from back in the 1200s CE, when their ancestors lived in the canyons and valleys west of Mesa Verde. When the Great Drought hit (around 1276 CE), they were already on the move because of other recent bad weather events. The kachina cult was developing around the same time and however it worked out, never took hold among the Tewa. The Tewas did incorporate the Medicine and Sacred Clown societies into their religious activities. Archaeologists have traced their tracks east from the Four Corners to the South San Juan Mountains, where they turned south and first built homes in New Mexico around Ojo Caliente. From there, they spread further south into the valley of the Rio Chama and then spread out there for a hundred years.

As more and more Dineh and Apaches came into the area in the 1400s, the Tewa moved downstream along the Chama. Some of them moved up onto the Pajarito Plateau while others sorted out into small villages on the east side of the Rio Grande. Shortly some of them came to the southern edge of the Santa Fe River Basin and found the Galisteo Creek Basin on the other side populated by Eastern Keres people. It was the same when they came to the mouth of the Santa Fe River at the Rio Grande: further south along the river was populated by other Eastern Keres people. And just upstream across the Rio Grande was the outlet of Frijoles Canyon, home of many Eastern Keres people in the 1400s and 1500s.

There were indigenous Tanoan people already living throughout the Rio Grande area and the two groups merged reasonably well. Somewhere in this time period, sodalities came into being: the Summer People and the Winter People. Some archaeologists believe the incoming Tewa became the Summer People and the Tanoans became the Winter People, based on the fact the incoming Tewas brought new seeds, new agricultural and ceramic technology, new dances and new religion. When the Spanish first arrived in the area around 1540 CE, the Tewa Basin was well occupied by the merged Tewa/Tano people. Those Tanoans who preferred not to merge built separate pueblos for themselves in more marginal areas in the Santa Fe and Galisteo River basins. Depopulation began after the Spanish left and didn't take their various diseases with them. It was after Don Diego de Vargas arrived in 1598 that the survivors were separated into their separate villages and restricted to those.

The Northern Tewa

The Northern Tewa design pallette contains a number of motifs common to many puebloan societies: hummingbirds, turtles, tadpoles, quails, owls, deer, hands, hoof prints, bird tracks and more. It's easy to see how many evolved from designs from the Flower World Complex of central Mexico. The Santa Clara and Nambé avanyu is a winding serpent with usually, one or three feathers on the top of its head. The San Ildefonso avanyu usually has a three- or five-pronged plume on its head. The avanyu itself is evolved from images of Quetzalcoatl. While the avanyu is the protective spirit of water and springs it also represents what happens when there's a heavy rain in the desert: flash floods that can wipe out whole villages.

Most San Ildefonso potters paint their decorations, only a few work with sgraffito decorations and a few work with inlaid stones and heishi beads. At Santa Clara, potters carve, scratch and paint their pieces, then sometimes reheat them with a blowtorch and mount stones on them... almost anything goes. The design palette is traditional to trend-setting contemporary, although the subject matter is usually the avanyu, or hummingbirds, turtles, quails, fish, deer, bear paws and bear claws, etc.

Because they had easy access to micaceous clay, the people of Nambé and Ohkay Owingeh built a brisk business in making micaceous pots and cookware, similarly to the people of Taos and Picuris at the time. More recently, Lonnie Vigil and Robert Vigil have produced micaceous pottery at Nambé while Clarence Cruz has been producing micaceous cookware and utensils at Ohkay Owingeh.

The people of Ohkay Owingeh decided to start over after essentially losing their pottery tradition in the 1800s. They never stopped making utilitarian pottery but even that declined in the late 1800s. In the 1920s, when it was decided they would work to revive a purely Ohkay Owingeh tradition, they settled on the designs found on some prehistoric pottery that had been found while digging in an old Tewa pueblo on Ohkay Owingeh land. The pottery was dated to the few decades before the Spanish arrived, hence: pre-contact and innocent of European influence. Their definition of Potsuwi'i pottery is very specific as to the colors and textures of the clay used and the designs carved, scratched or painted on them. Many of the design patterns are reflective of rock art from a thousand years ago.

The Southern Tewa

The Santa Fe Basin is where the Southern Tewa settled. They seem to have followed the idea that "further south is a better life," and they kept going south until they came up against other relatively entrenched people (migrants spreading out from Santo Domingo into the Galisteo Creek Basin). The Santa Fe Basin showed signs of having been occupied by the Tanoan people off-and-on over the centuries. It was a marginal landscape for farming but it was up against the Cerrillos Hills where they found turquoise, silver and lead ore. The turquoise trade was very profitable for some but the lead ore made possible different design techniques to use on fired pottery. The potters of the village did well producing lead-glazed pottery (not sealed, glazed only where the lead paint was applied and then ran in the heat of the fire).

In 1692, when the Spanish arrived in full force to reconquer northern New Mexico, most of the Tewa people in Tewa Basin gathered atop Black Mesa, a volcanic plug that sits between Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos. They stayed up there for months, almost impervious to Spanish attack. Eventually, though, they made a deal with the Spanish and returned to their various pueblos.

Shortly after that, the Spanish issued an order limiting access to the lead mines at the Cerrillos Hills to Spanish citizens only and, with that, the Southern Tewa lost their last possibility for remaining in a parched landscape. Because of the boundaries imposed by the Spanish, they all ran north in the night to the area of Chimayo. That didn't work out quickly, so they moved to the area of Santa Clara, again during the night. That didn't work out either as they were challenged by a Spanish priest and they killed him. From there they moved quickly to the area of Zuni, then up to First Mesa where they made a deal with the people of Walpi and were shortly living in their own village near the base of First Mesa. Over the centuries they came to be known as the Hopi-Tewa. In that same time period many of the religious aspects of Hopi society have made their way into Hopi-Tewa society. The Hopi-Tewa design pallette consists mostly of designs revived from potsherds found around the ancient pueblos of Awatovi, Sikyátki, Payupki and Kawaika'a, all of which are in the vicinity of the Hopi mesas.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

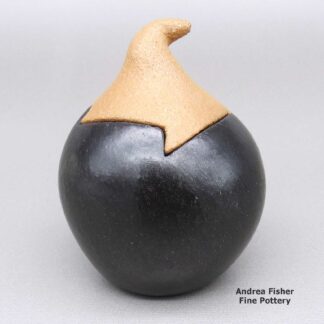

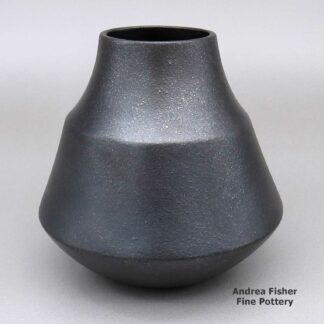

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.