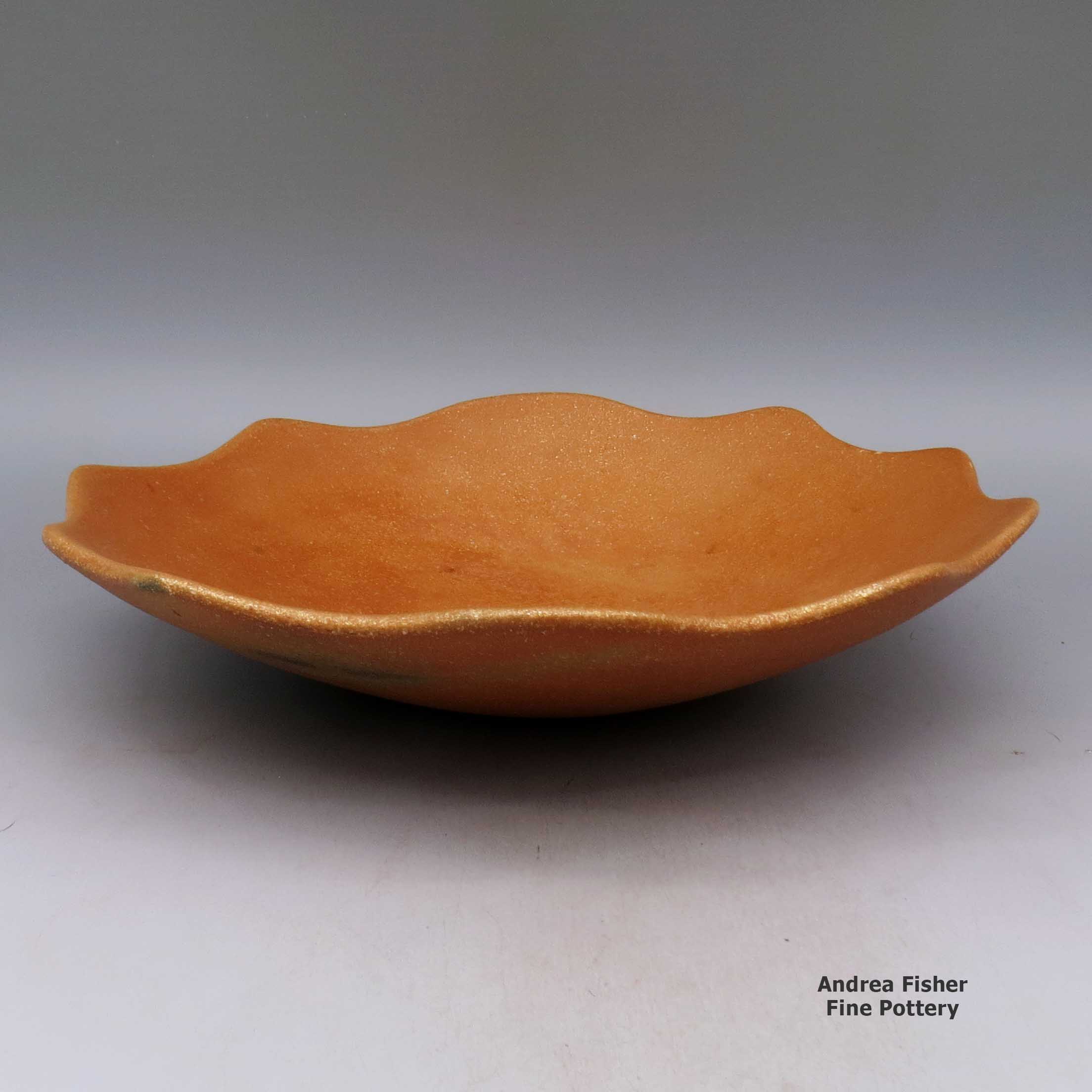

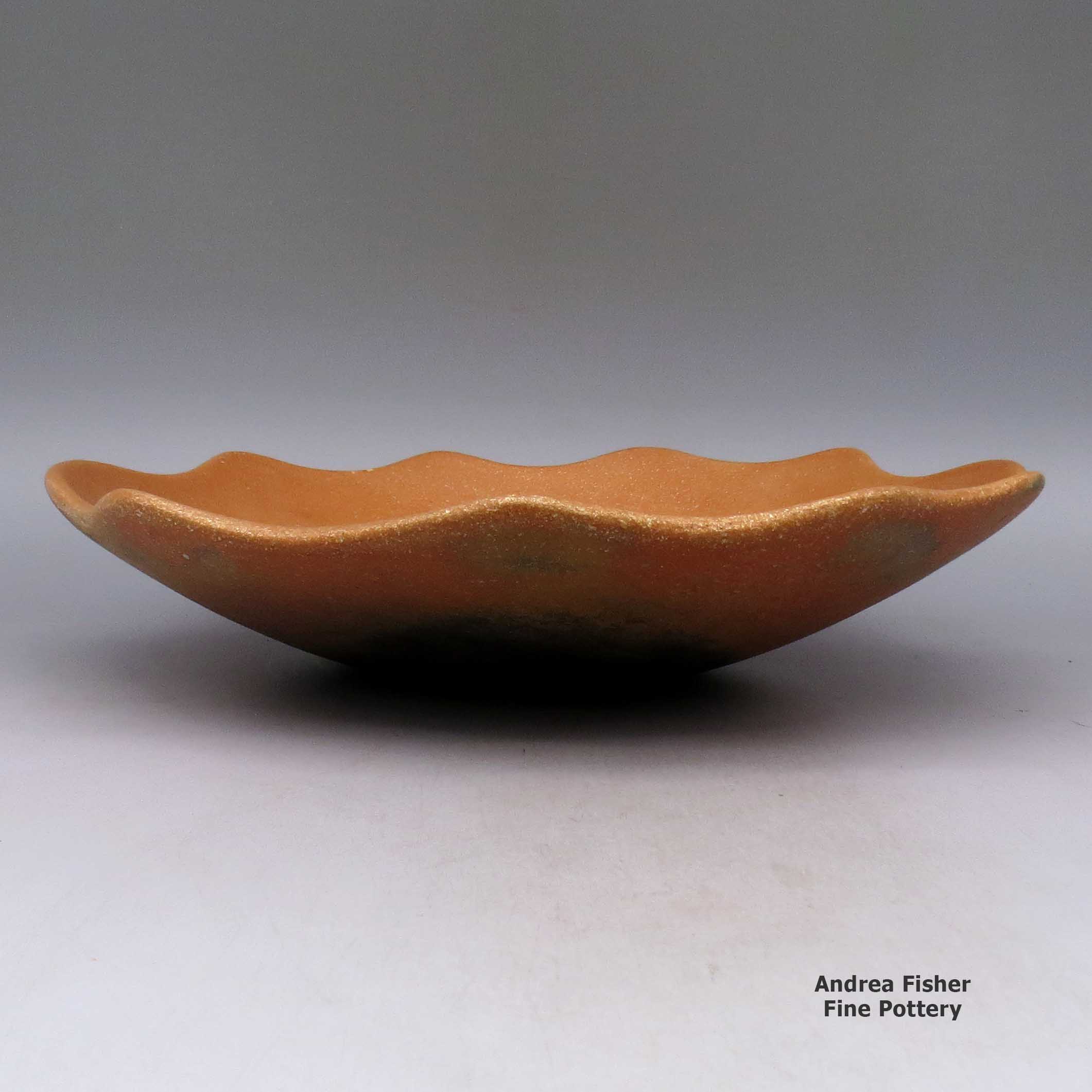

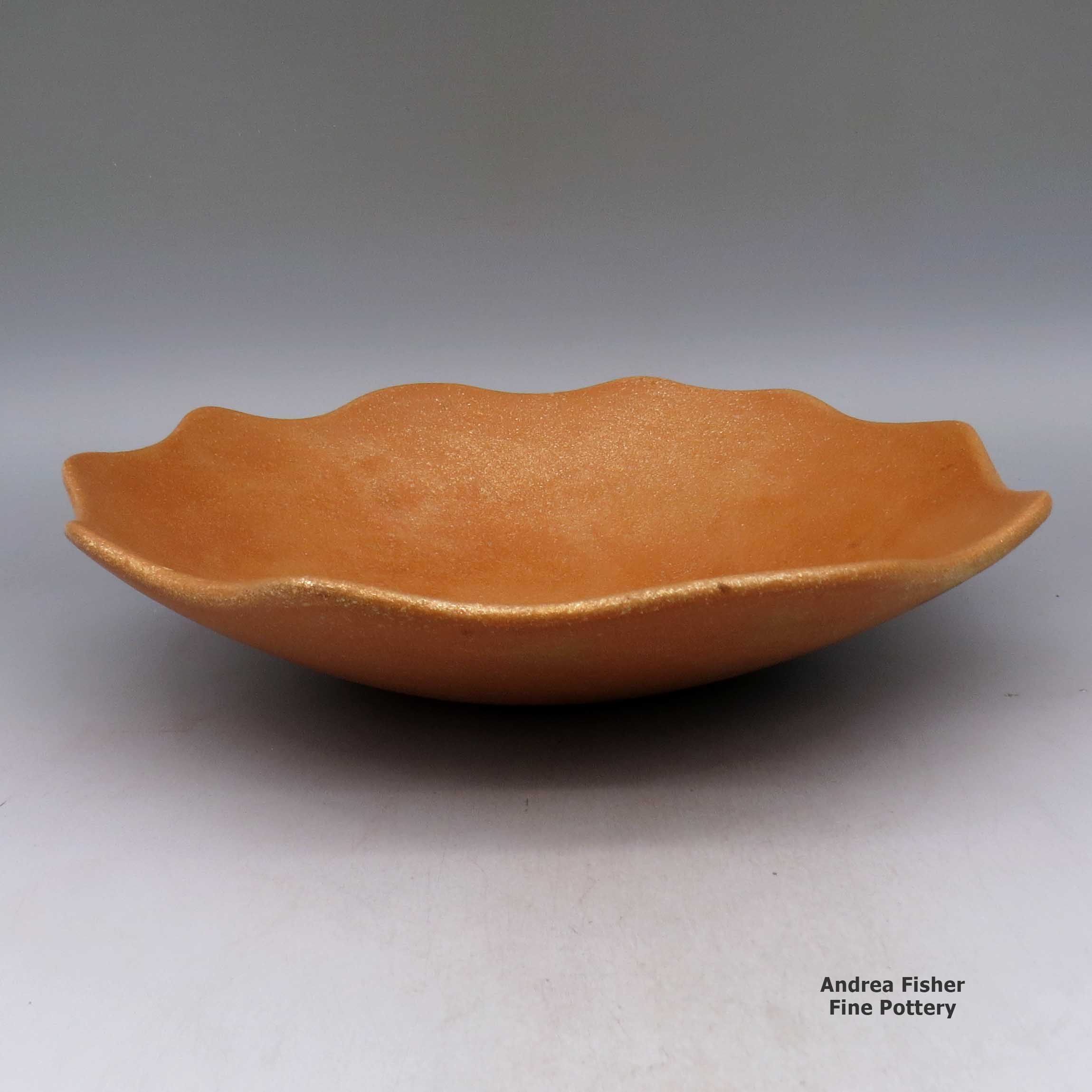

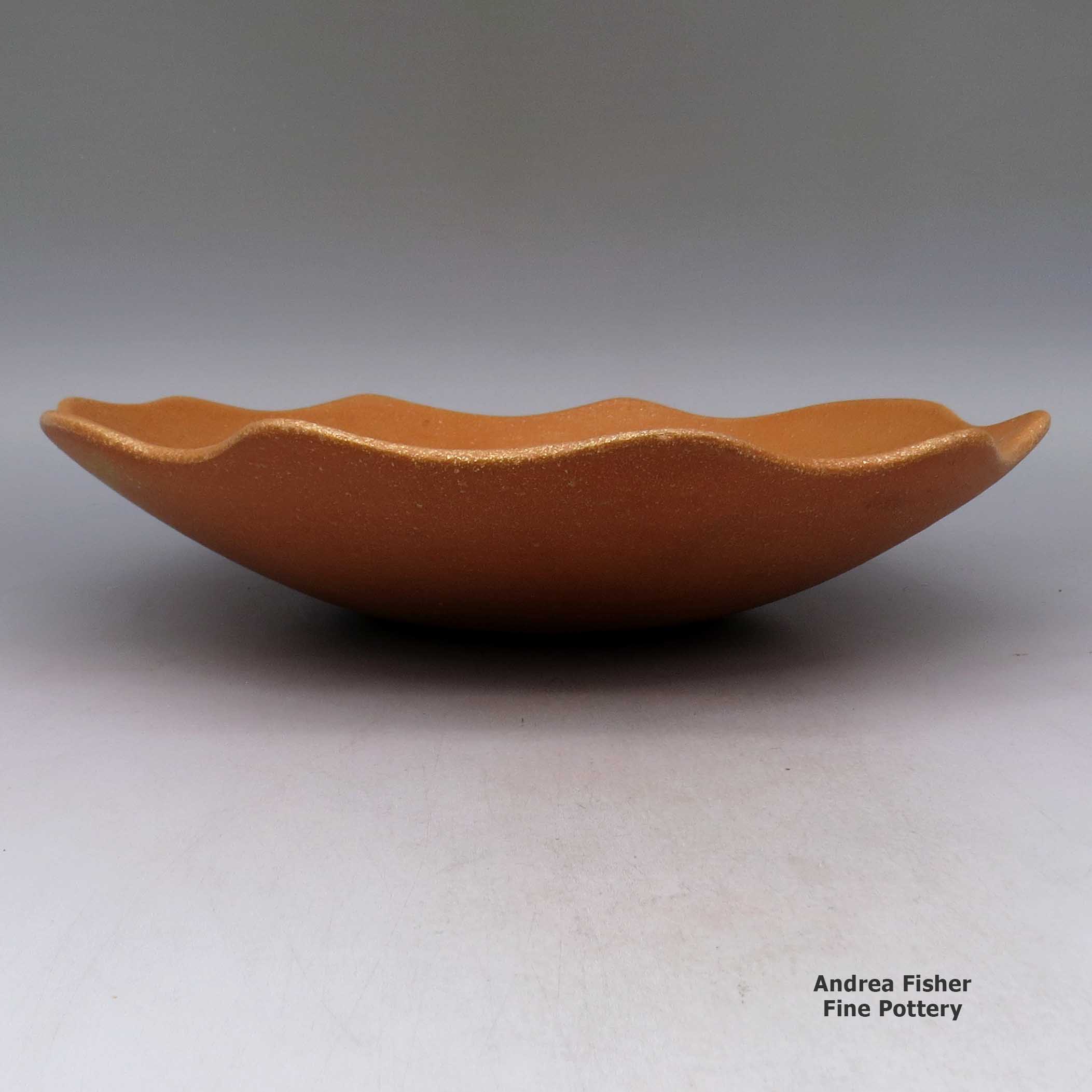

| Dimensions | 13.25 × 13.25 × 2.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Vigil Nambe |

Lonnie Vigil, spna2l080, Golden micaceous shallow bowl with scalloped rim and fire clouds

$2,200.00

A golden micaceous shallow bowl with a scalloped rim and fire clouds

In stock

Brand

Vigil, Lonnie

Born in May 1949, Lonnie Vigil said he had no conscious desire to become an artist when he was growing up at Nambe Pueblo. Instead, he finished high school and went on to earn a degree in business administration from Eastern New Mexico University. Then he pursued a career as a financial and business consultant, first at the Eight Northern Pueblos office in New Mexico and then at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.

By the early 1980s, he was becoming aware that his work and life in Washington "gave me nothing to feed my soul." A performance at the Kennedy Center called Night of the First Americans inspired him to return to Nambé.

At first he spent days wandering the pueblo lands and praying, seeking a vision to follow into his future. He discovered a source of micaceous clay on pueblo land, then he found polishing stones in the ruins of his grandparents' home. That's when he got his first inkling that the rest of his life would be "committed to the Clay Mother."

In the beginning, it was hard because there was no one to teach him. "I prayed for direction from the Clay Mother and slowly the information began to come," he says. "I also asked for the help of my great-grandmother and my great-aunts, who were all potters. And I still ask their guidance today."

Apparently he was guided into re-creating Nambé Pueblo's famous micaceous clay pottery. But Nambé potters used to use micaceous clay to seal their pots for use in cooking and storage while Lonnie has elevated the use of micaceous clay to the state of a fine art.

He practiced working with micaceous clay until one day in 1994 he was declared the first recipient of the Ron and Susan Dubin Native American Artist Fellowship at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe. Upon receiving the fellowship, Lonnie said, "I am honored to be the first Dubin Fellow at such a fine institution as the School for Advanced Research. The Fellowship is an affirmation of the work I am doing." That support allowed him to take the time to study the ancient micaceous pottery in their collections.

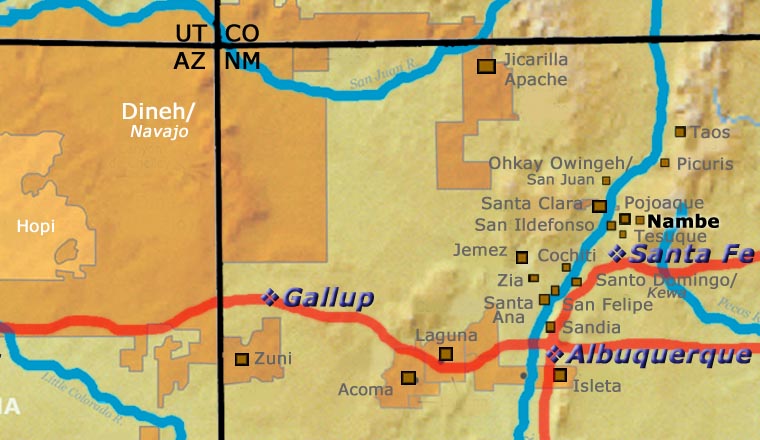

Micaceous pottery is distinguished by the sparkling mica flecks naturally distributed in the clay. Historically, micaceous pottery was used for cooking and storage by the people of Nambé, Picuris, Taos and the Jicarilla Apache. Overlooked by many collectors in the past, Lonnie Vigil has been characterized as single-handedly reviving unpainted micaceous clay pottery and establishing it as a contemporary art form.

Lonnie's signature large pots have earned the top awards at several Santa Fe Indian Markets (including the Best of Show ribbon in 2001) and he was honored with the Native Treasures 2010 Living Treasure Award. He sees himself as "a guardian of the clay" and says, "I feel responsible for making sure that the Clay Mother stays alive in my village."

Working with the School for Advanced Research, Lonnie helped to organize the first Micaceous Pottery Symposium and Market in Santa Fe in 1995. His work is shown in museums around the world, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Indian Arts Research Center, the Smithsonian Institute and the Horniman Museum in London, England. His work is also found in many private collections, including that of his holiness, the Dalai Lama.

Some of the Exhibits that have Featured Lonnie's work

- Something Old, Something New, Nothing Borrowed: New Acquisitions from the Heard Museum Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. April 2, 2011 - March 18, 2012

- Gifts of the Spirit, Works by Nineteenth-Century and Contemporary Native American Artists. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, Massachusetts. November 15, 1996 - May 18, 1997

- Fifth Annual Hollywood Premier. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, Arizona. November 23-24, 1991. Note: held at the Four Seasons Hotel, Los Angeles, California

About Nambé Pueblo

Nambé Pueblo was settled in the early 1300s when a group of Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) made their way from what is now the Bandelier National Monument area closer to the Rio Grande in search of more reliable water sources and more arable land.

At first they settled mostly high in the mountains, coming down to the river valleys in the summer to grow crops. Eventually, they felt safe enough to stay in the valleys and slowly abandoned the high mountain villages.

When the Spanish first arrived, Nambé was a primary economic, cultural and religious center for the area. That attracted a large Spanish presence and the nature of that presence caused the Nambé people to join wholeheartedly in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 to throw out the Spanish oppressors.

When the Spanish returned in 1692, their rule was significantly less harsh. However, the Spanish brought horses into the New World and as the number of Spanish increased, so did the number of horses. That brought more and more raids from the Comanches as they came for horses and whatever else they could carry away. The Comanches were finally subdued by Governor Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776 but by then, the impact of European diseases was being strongly felt. A smallpox epidemic in the late 1820s virtually ended the making of pottery at Nambé.

Photo courtesy of John Phelan, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

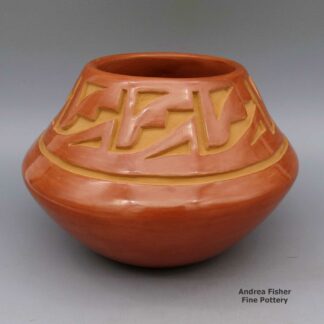

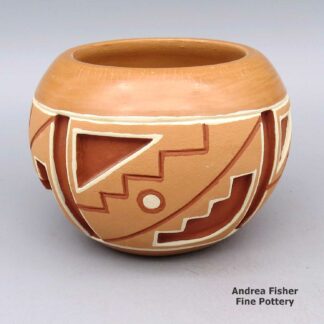

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

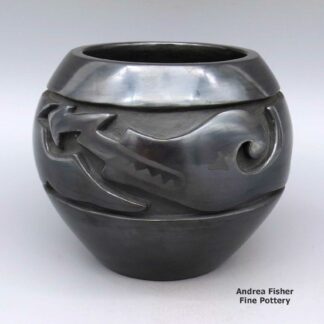

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.