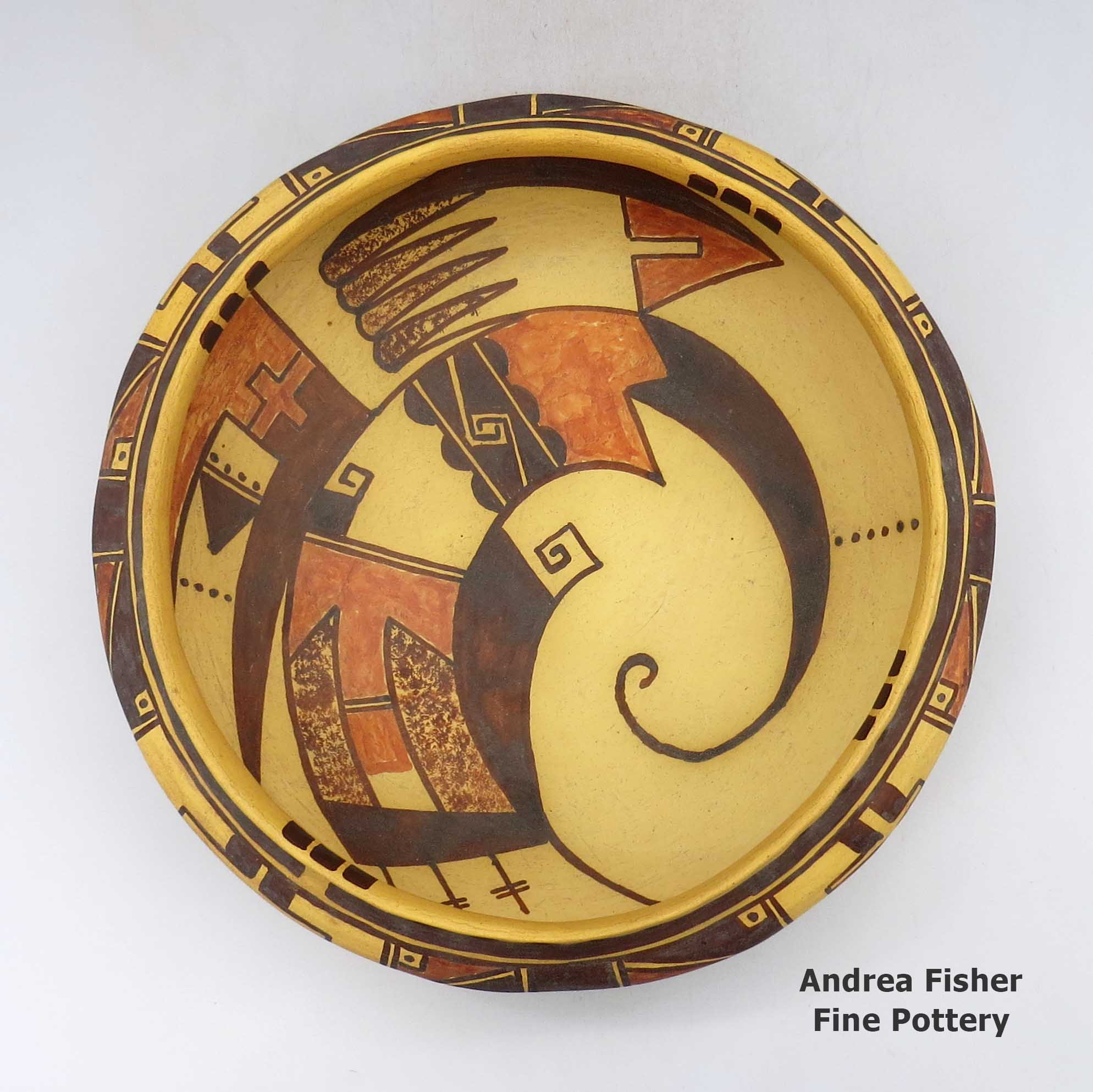

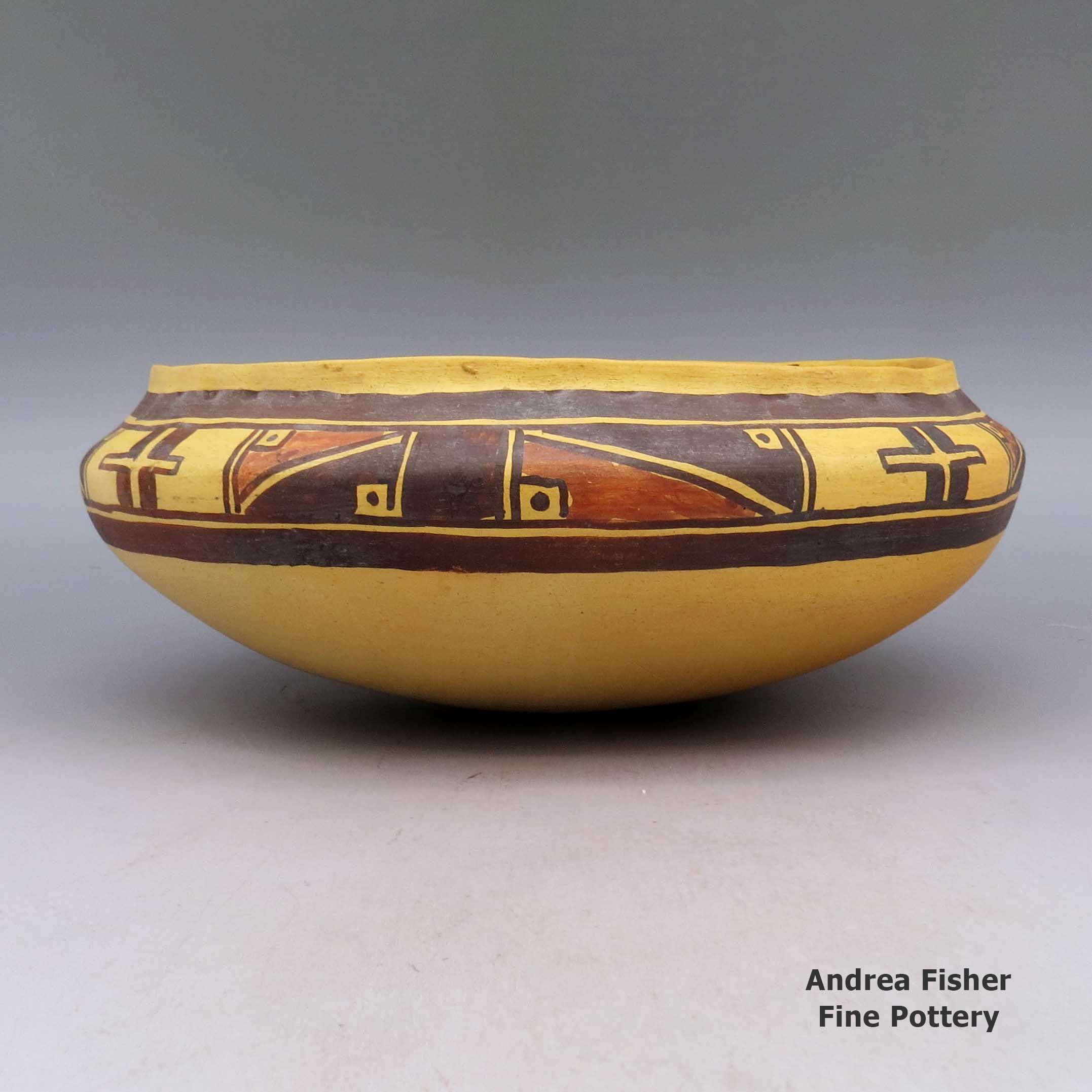

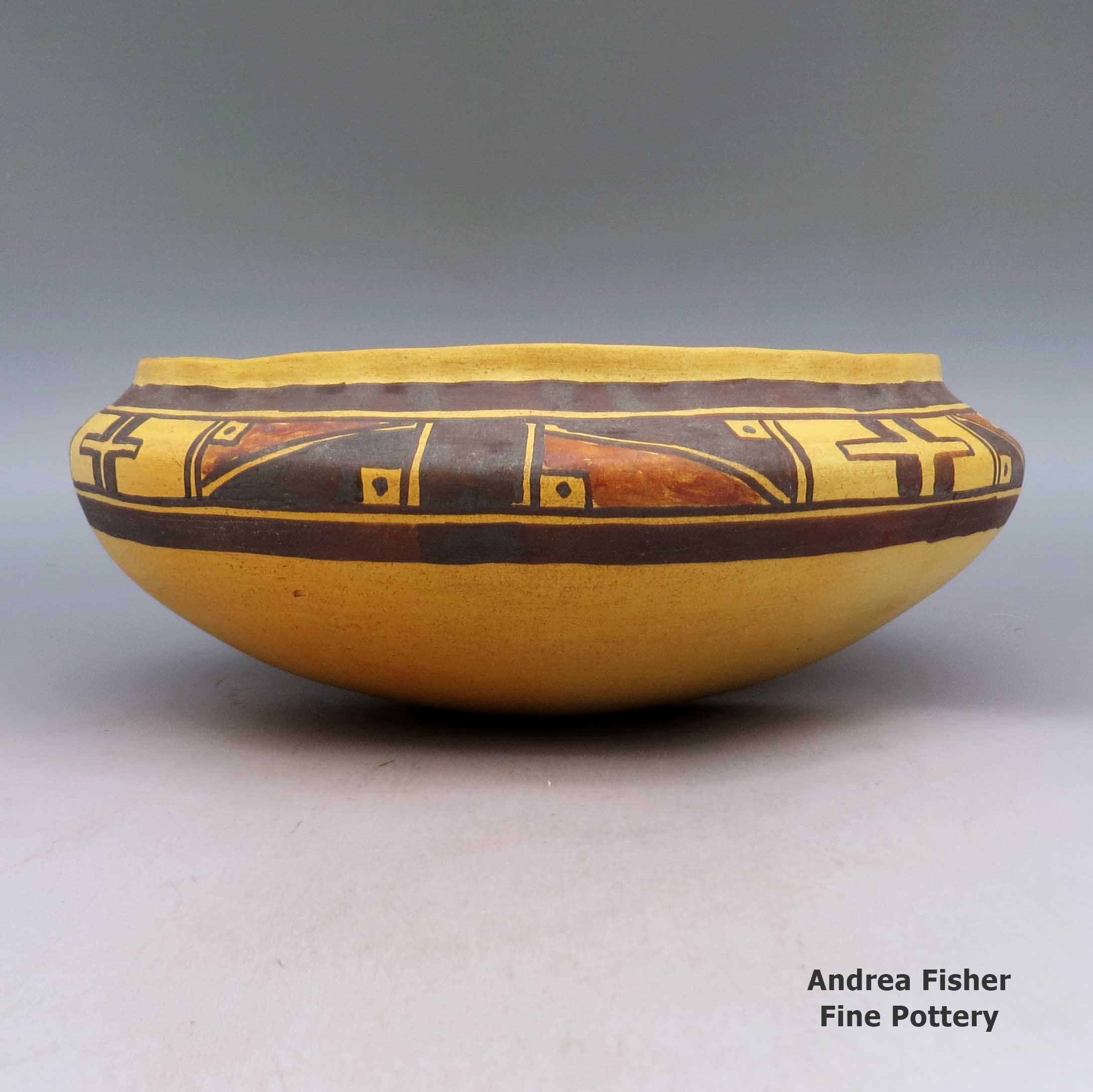

| Dimensions | 10 × 10 × 4 in |

|---|---|

| Signature | Chakoptewa X90B1, with pipe hallmark |

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

Michael Hawley, esho2g013, Polychrome bowl with geometric design

$1,400.00

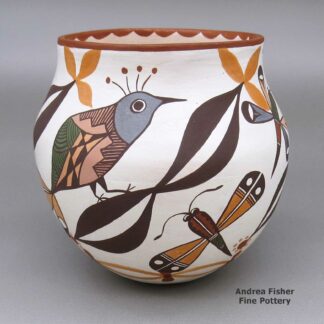

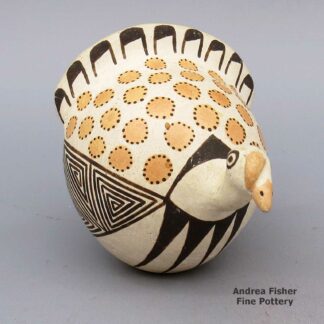

A polychrome bowl decorated with a Sikyatki Revival bird element and geometric design, inside and out

In stock

Brand

Hawley, Michael

He dug all his clay on Antelope Mesa, used only vegetal and mineral paints and ground-fired his pots in a pit using coal, just like the ancients did. He called it "Chakoptewa Polychrome," in honor of his name: Chakoptewa (meaning: friendly white man). The majority of his pieces were in the Sikyátki-Revival (which is now termed "Hano Polychrome") style.

Sikyátki Revival and The Evolution of Hano Polychrome

The name "Nampeyo" has been associated with much of the pottery produced on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona since the late 1800s. The first potter in the line, Nampeyo of Hano, just happened to be the right person in the right place at the right time. She re-interpreted and re-introduced various proto-historic forms, designs and color schemes, becoming the icon of a new/old approach to the making of pottery that was quickly adopted by other potters. This new style eventually came to be known as "Sikyátki Revival Ware." It was associated with archaeological excavations that were conducted during the 1890s at the ruins of Sikyátki, a Hopi village which had existed between about 1375 and 1625 on the east flank of First Mesa, about three miles north of Hano.

The common story is that Nampeyo's husband Lesou was hired by archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes in 1895 to help in the excavation of Sikyátki. As Fewkes told it, Lesou told Nampeyo about the pottery he'd seen at the site and his descriptions sparked her interest. She visited the site and saw first-hand the finely made, impeccably decorated jars and bowls that were being discovered and removed. Supposedly influenced by what she saw, Nampeyo’s work changed to emphasize highly stylized bird forms, especially macaws and eagles.

In reality, Lesou never worked for Fewkes and Nampeyo was well known for producing high quality Sikyátki-Revival Ware before Fewkes ever arrived in the area. No one called it that back then but it was what local traders like Thomas Keam and Lorenzo Hubbell were asking for when potters would bring them pots for sale. The traders wanted shapes, colors and designs like those that littered many of the old ruins in the area.

The mounds at what were Sikyátki, Awatovi and Jeddito yielded many distinctive shapes and designs, long before Fewkes arrived. Nampeyo drew some of her inspiration from other ancestral Hopi pottery types such as Jeddito and Awatovi Black-on-Yellows. Some of the designs she used have been traced west to Tsegi Canyon and Homol'ovi, northwest to Grand Gulch and south to FourMile Ranch (more than 100 miles from where she lived).

Describing Sikyátki-Revival Ware (or "Hano Polychrome," to be more accurate) is difficult. The pots are uniformly polychrome, employing vegetal and mineral paints that fire to become the reds, browns, yellows and blacks that we associate with Hopi pottery these days. The designs employ graceful, curvilinear lines that are well balanced across the three-dimensional surface of the pot. The designs also frequently incorporate religious symbols. The shapes are distinctive: wide shouldered flattened jars, low bowls with decoration inside and seed jars with small openings in their centers and tops that seem to defy the laws of physics as dictated by the clay.

The base clays polish and fire to an unusually smooth texture, with colors ranging from golden yellow to orange to light brown. Since the fired surface came out so smooth, no slip had to be applied to the overall surface prior to applying the designs.

The pueblos of Hopi and Zuni developed a close relationship in the 1880s when many Hopis left the Hopi mesas during a drought and smallpox epidemic and waited at Zuni for conditions to improve so they could return. This connection influenced Hopi potters when they saw the Zunis use a white slip under their decorations. That practice returned to Hopiland when the potters returned and it was used in the production of "Polacca Ware," the most common form of Hopi pottery being made until the late nineteenth century. Polacca Ware is characterized by a white background with a "crackled" surface.

At the encouragement of local traders Thomas Keam and Lorenzo Hubbell, some Hopis started recreating old styles and designs based on the shapes and designs implied by ancient pot shards they found among the ruins left by their ancestors. Nampeyo was among the potters who were making quantities of non-utilitarian pottery for trade purposes and she heard Keam's call.

Like most other potters in the area, she was making Polacca Ware and decorating it with a large vocabulary of ancient designs. Her innovation was to abandon the use of the white slip and apply her decorations directly to the polished clay body, just as she'd observed on the ancient pots. (The Navasie/Naha families still make their pottery using the white slip but their process wasn't perfected until the early 1950s and now it's called "Walpi Polychrome.")

Nampeyo was relatively prolific in her making of pots. She also had an excellent eye for design and a steady hand for painting her designs. She and her descendants have set the quality bar for Sikyátki-Revival (Hano Polychrome) pottery very high and that level of quality continues to rise today.

The tremendous diversity of design and technique in modern Hopi pottery stands as testament to its long history and the care with which today's Hopi and Hopi-Tewa potters seek to preserve their heritage while continuing to innovate and evolve the medium.

Accomplished potters from some of the Rio Grande Pueblos have also created Sikyátki-Revival/Hano Polychrome pieces. Among them is Tonita Roybal of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Les Namingha, a 1/2 Hopi, 1/2 Zuni potter creates Sikyátki and Hawikuh-Revival pottery.

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Bird Elements

One of the main tenets of the Flower World ideology is that birds are messengers to and from Paradise. They carry our prayers to Heaven and they bring back the responses. Not all the pueblos accepted the Flower World ideology but it seems almost everyone, almost everywhere, agrees that birds are the messengers of Heaven. All pueblos do have multiple designs that incorporate feathers, if feathers aren't the main element of the design.

The Flower World ideology originated in central Mexico and most likely traveled north to the pueblos in the company of missionaries and long-distance traders. Turquoise was taken south while tropical birds, copper bells, seashells, and textiles (with particular spiritual designs on them), along with other spiritual items, were taken north. Going either way, almost everyone passed by Paquimé. The trade routes from the south came together there and the trade routes to the north diverged from there. That business didn't really come together until the first structures went up in the immediate vicinity of Paquimé, around 1150 CE. Then it ended around 1450 CE when the city was abandoned. That was also the end of pilgrims making their way south and then coming north again a few years later. For more than 300 years that traffic had been a major profit center and prestige generator for the people of Paquimé and Casas Grandes. After Paquimé was abandoned, though, the trade and pilrimage routes became far more dangerous. With the advent of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico, being a foreigner in that area became far more dangerous, too. Essentially, the puebloans who had embraced the Flower World ideology were cut off from their Holy Land.

The Flower World Complex, with its symbology, flowed across the American Southwest and eventually reached the Four Corners area. But it arrived at about the same time the kachina cults were coming together and the people were abandoning the Four Corners. The Flower World ideology was felt to be greater than what had come before so it's symbology was basically imprinted on top of that. Then the designs of the kachina cults and other clans were added on top of the Flower World symbology. Then came the Europeans with their designs and spiritual practices.

One of the principals of Native American design is that it is necessary only to note one part of most animals to imply the presence of the whole, especially when it comes to birds and bird elements. A lot of the design on Hopi pottery can only be described as "bird elements," although it is often possible to discern parrot feathers from eagle feathers, and eagletails from other bird's tails.

The Zunis have an ancient "almost-spiral" design that comes from the beaks of their equally ancient "rainbirds." The Zunis also like to make owl figures as owls are a symbol of wisdom to them. To some Northern Tewas, owls are creatures to be feared.

At Acoma they have a "cloudeater," a crane pictured with neck bent over and filling with fish shown sideways in its throat as it swallows them whole. Acoma potters also have a parrot that resembles the parrot found on the sides of the boxes carried by Amish traders back in the day. The parrot is not complete without a branch with leaves, and maybe berries, in its claws.

At Santo Domingo, religious dictates limit what can be imaged on pottery offered to the public. Birds, fish, turtles and flowers are allowed, along with a vast catalog of geometric designs. Images of humans are not. Next door at Cochiti, almost anything goes

The artists of the Mata Ortiz area are resurrecting some of the designs left behind by artists of old but they have no inner connection with the Flower World. Others in today's Mata Ortiz have gone totally contemporary: carving, scratching and painting beautiful images of birds with branches, vines and flowers.