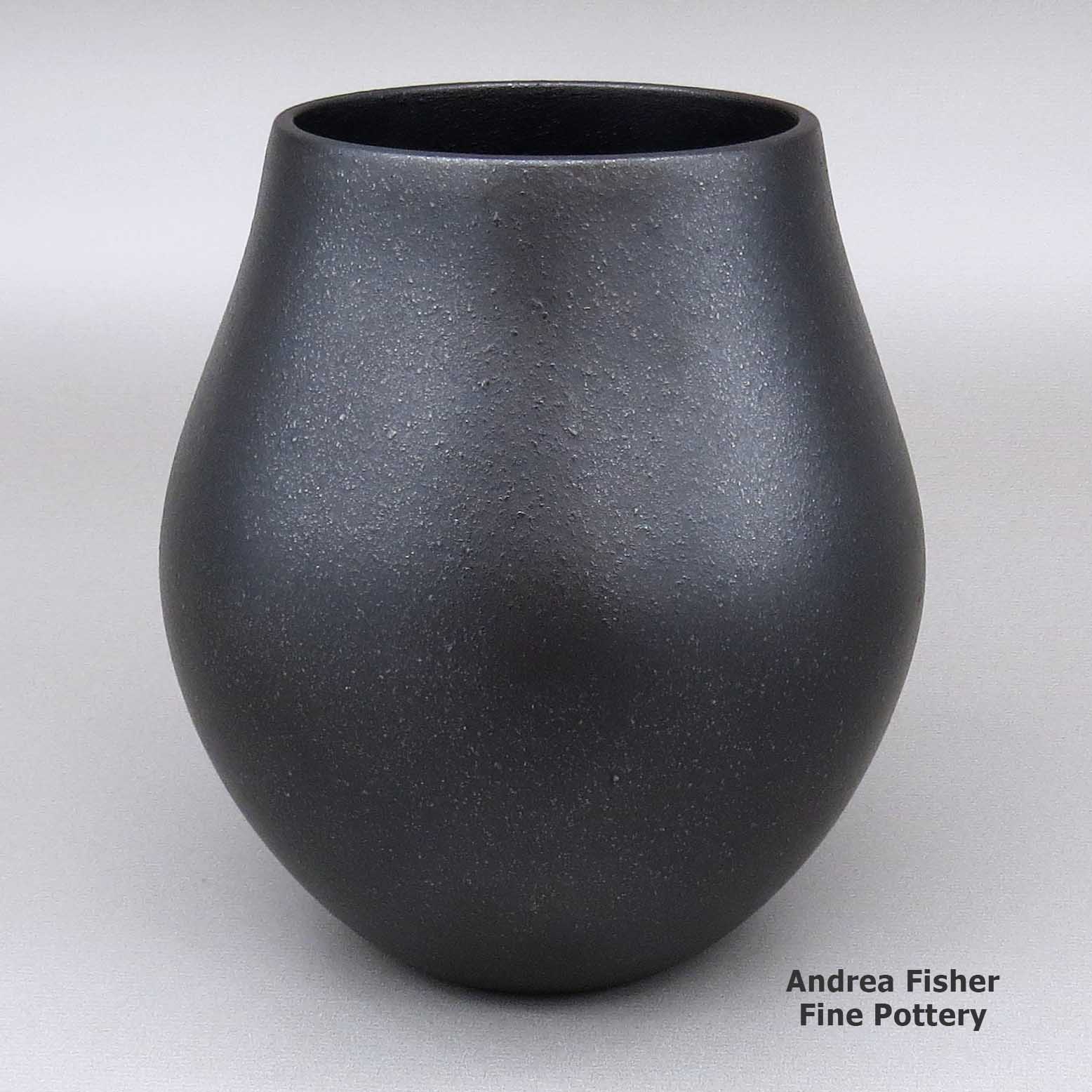

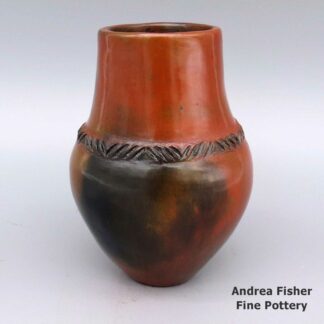

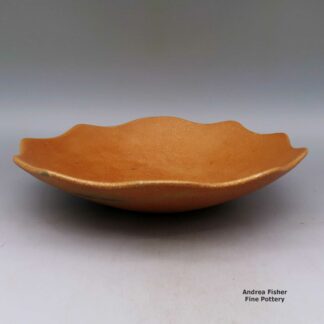

| Dimensions | 5 × 5 × 6 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Robert Vigil Nambe |

Robert Vigil, zzna3a130, Micaceous black jar

$295.00

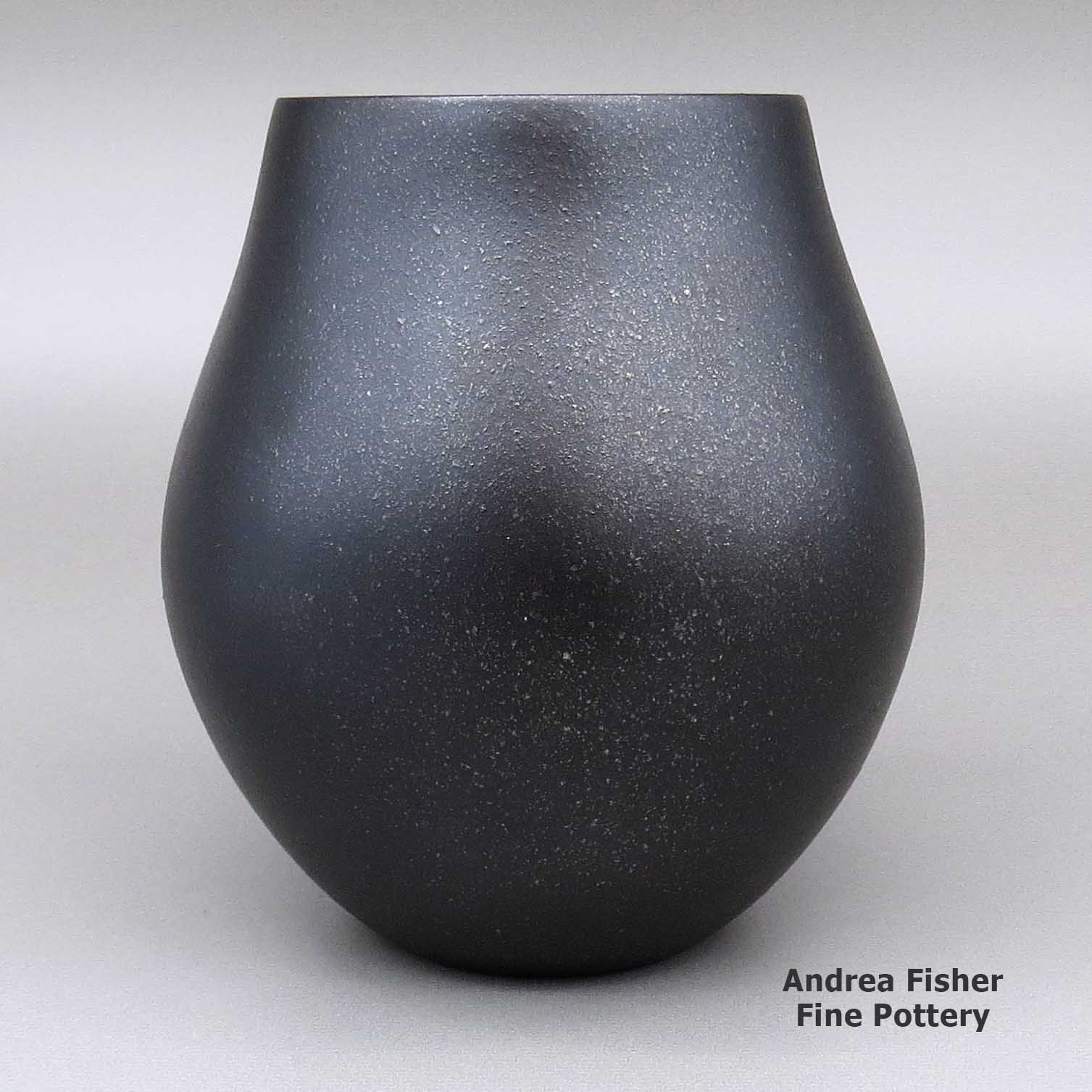

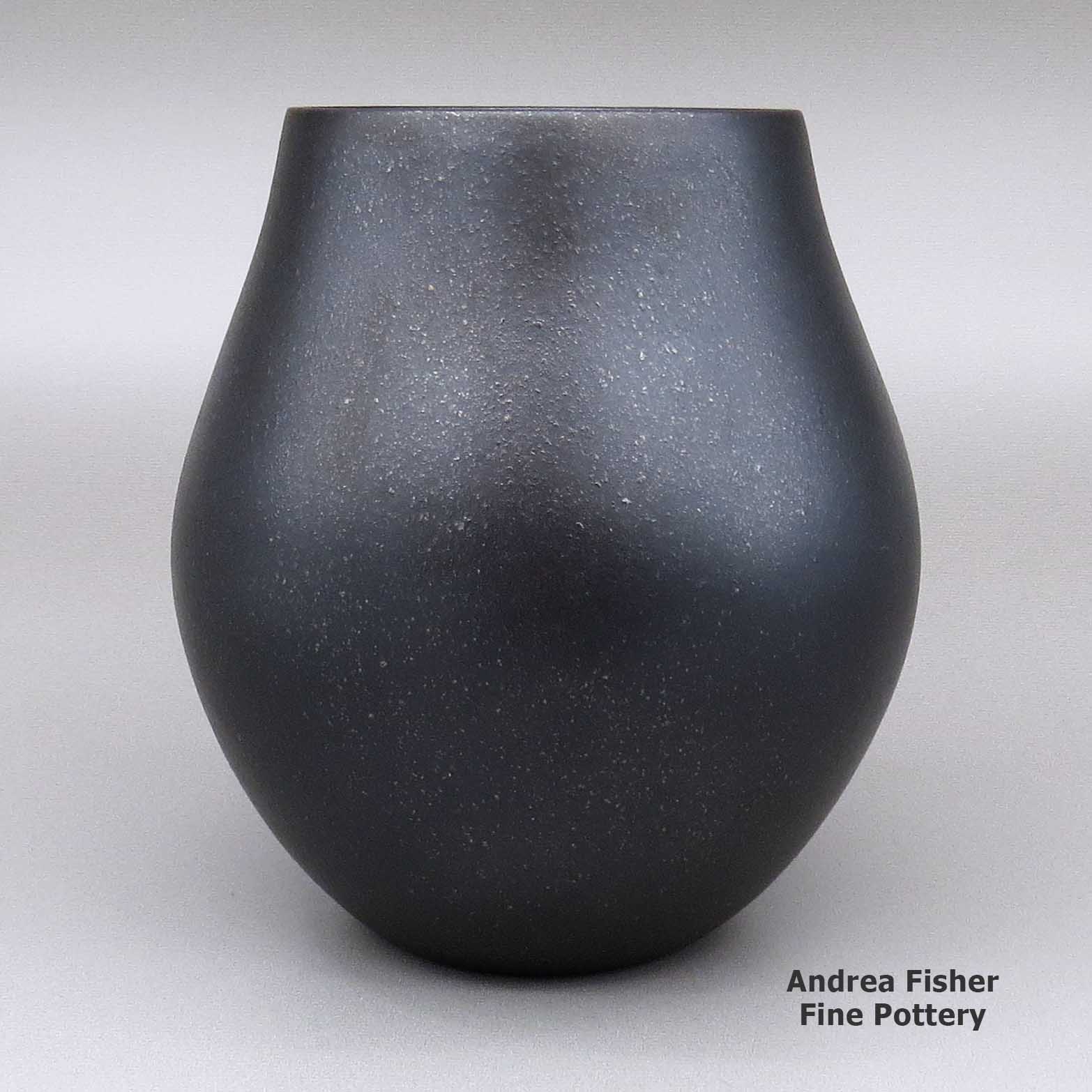

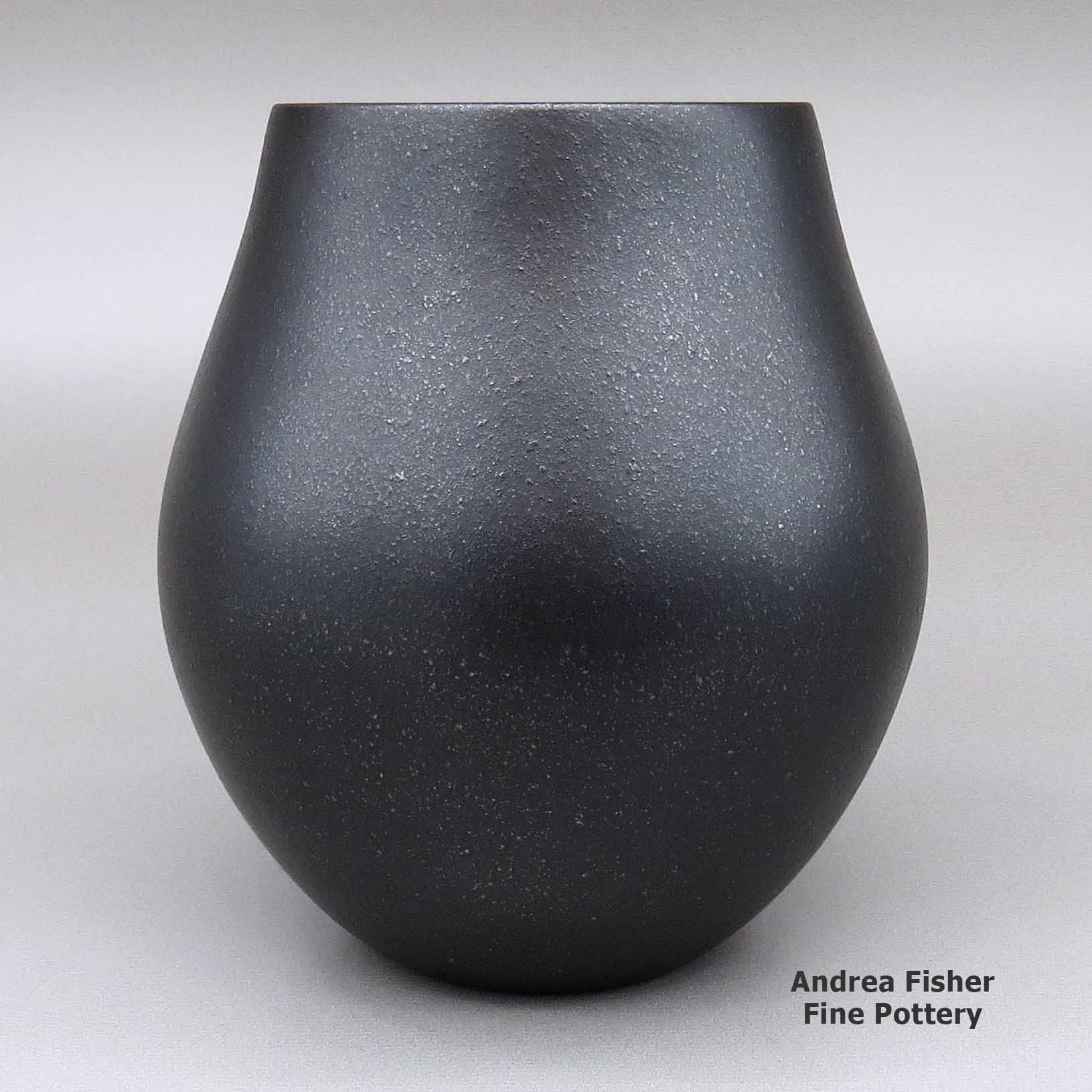

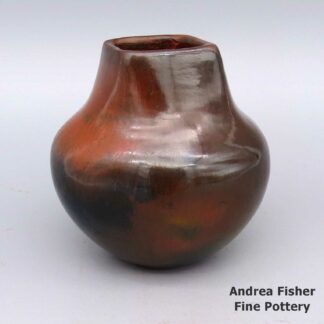

A black micaceous jar with fire clouds

In stock

Brand

Vigil, Robert

"I just sit down and start and the clay forms itself through my hands."

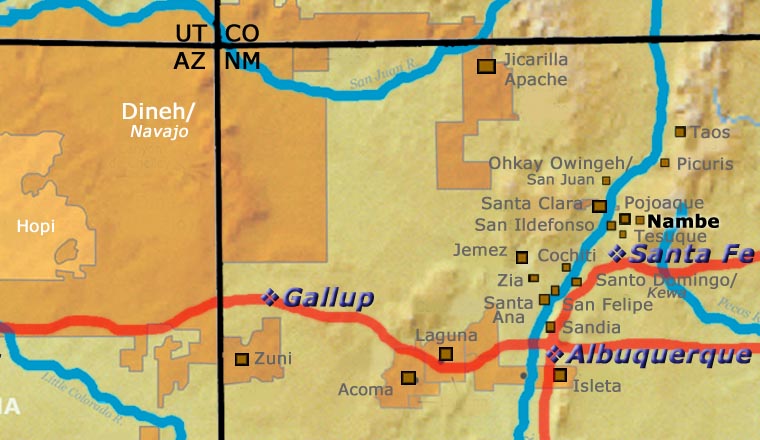

"I just sit down and start and the clay forms itself through my hands."Half Nambe Pueblo and half Non-Pueblo, Robert Vigil was born to parents Joe and Alice Vigil in 1965. He first learned the method of making pots with clay coils while in high school in Texas. Then he returned to the pueblo and began to learn from folks like Virginia Gutierrez, his cousin Lonnie Vigil and then from Juan Tafoya of San Ildefonso Pueblo. Robert has been active as a Nambe potter since 1990 working with micaceous jars, bowls, vases, figures and polished redware.

Robert doesn't create giant storage jars like his cousin Lonnie. He much prefers to work on a smaller, more intimate scale. He colors his micaceous pots with fire clouds and other variations produced by the method of firing. There is an elegant purity to his simplistic and understated forms, a deep reflection of his soft spoken manner and gentle spirit.

Robert has told us he prefers the simple shapes and forms and even his carving is gentle. He gets his inspiration from the clay: "I just sit down and start and the clay forms itself through my hands." He's lately been teaching others at his pueblo how to make pottery the traditional way as he doesn't want to see that tradition get lost over time.

Robert has participated in shows at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, at the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts and Crafts Show and at the First Micaceous Pottery Market and Symposium in 1995 in Santa Fe. Pieces of Robert's micaceous pottery are on display at the Minneapolis Art Institute in Minneapolis, MN, and at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, among others.

About Nambé Pueblo

Nambé Pueblo was settled in the early 1300s when a group of Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) made their way from what is now the Bandelier National Monument area closer to the Rio Grande in search of more reliable water sources and more arable land.

At first they settled mostly high in the mountains, coming down to the river valleys in the summer to grow crops. Eventually, they felt safe enough to stay in the valleys and slowly abandoned the high mountain villages.

When the Spanish first arrived, Nambé was a primary economic, cultural and religious center for the area. That attracted a large Spanish presence and the nature of that presence caused the Nambé people to join wholeheartedly in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 to throw out the Spanish oppressors.

When the Spanish returned in 1692, their rule was significantly less harsh. However, the Spanish brought horses into the New World and as the number of Spanish increased, so did the number of horses. That brought more and more raids from the Comanches as they came for horses and whatever else they could carry away. The Comanches were finally subdued by Governor Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776 but by then, the impact of European diseases was being strongly felt. A smallpox epidemic in the late 1820s virtually ended the making of pottery at Nambé.

Photo courtesy of John Phelan, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Fire Clouds

Fire clouds are a product of the firing process. They are generally random darkenings of a piece where it was touched by a wayward plume of smoke and the clay absorbed some of the carbon in it. Conversely, in an oxygen-reduction atmosphere (which is how Tewa potters turn their otherwise red pieces black), surfaces randomly exposed to open air don't turn as black while surfaces protected from exposure to the oxygen-reduction atmosphere turn red. In some pueblos, the appearance of fire clouds is a testament to the lack of experience of the potter. In others it's a testament to the greater experience of the potter.

Dineh potters often stack their firewood in ways to generate fire clouds on their brown clay as that may be the only decoration on the piece.

Fire clouds on Hopi pottery are usually seen as a darker blush on an otherwise yellow piece. That is a result of their yellower clay and their use of cedar bark and sheep manure for firing. Franklin Tenorio of Santo Domingo also often used cedar bark to fire his pieces but he liked to make his surfaces look smudged and smoky by partially blocking the air flows around his fires. In contrast, his cousin Thomas Tenorio prefers to fire his pieces inside a metal container that denies any entrance to fire-cloud generating smoke or atmosphere.

Potters who work with micaceous pottery also work with fire clouds. When firing in a free-oxygen atmosphere, fire clouds may be the only decoration on a piece. When firing in an oxygen-reduction atmosphere to produce a black piece, "fire clouds" are any lighter areas left on the surface after the firing is complete.