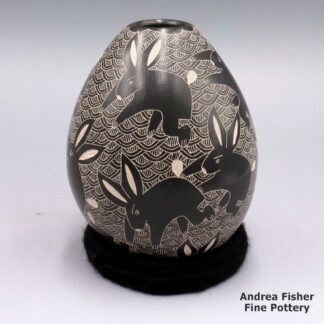

| Dimensions | 4.25 × 4.25 × 5.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Russell Sanchez |

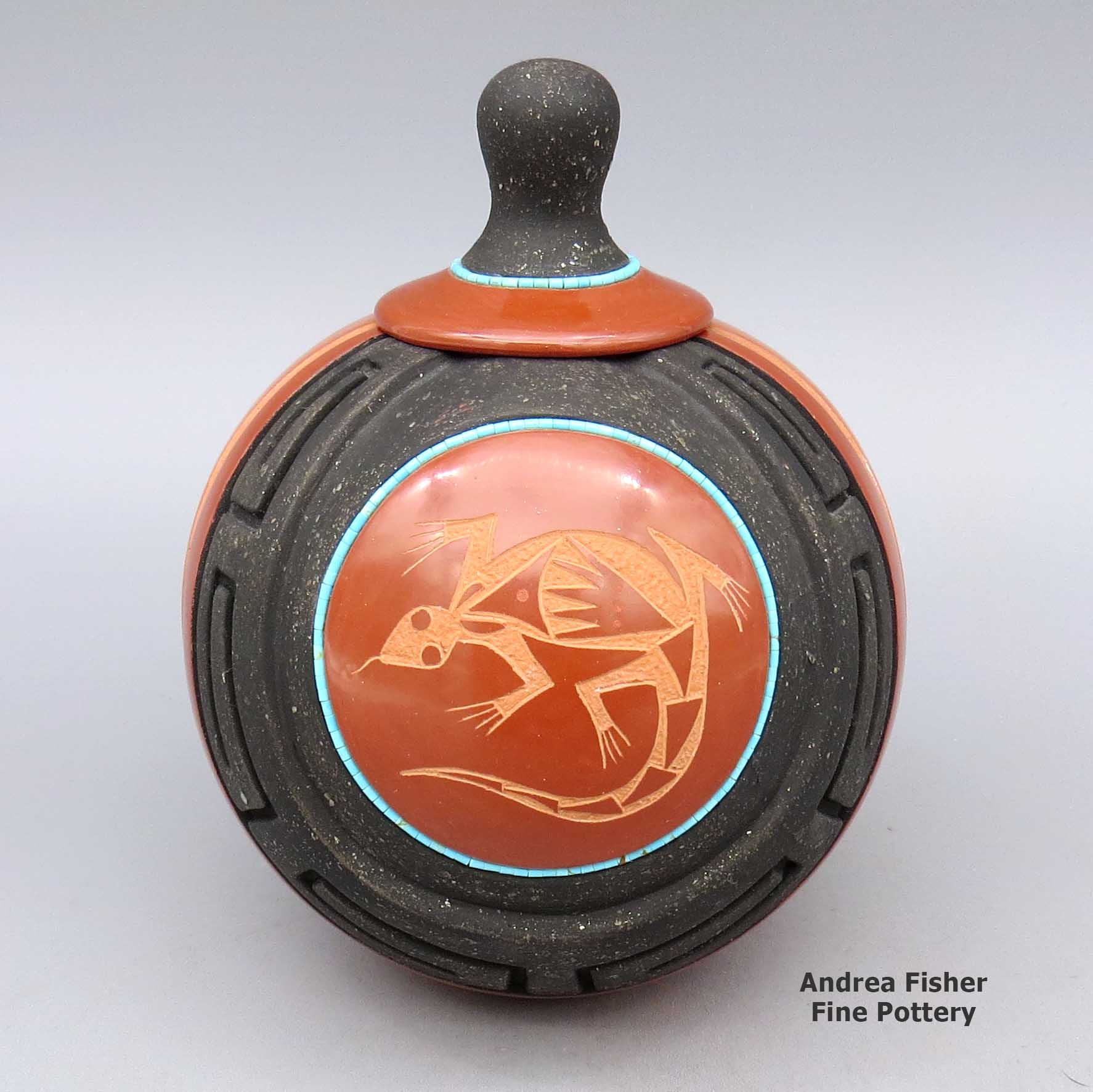

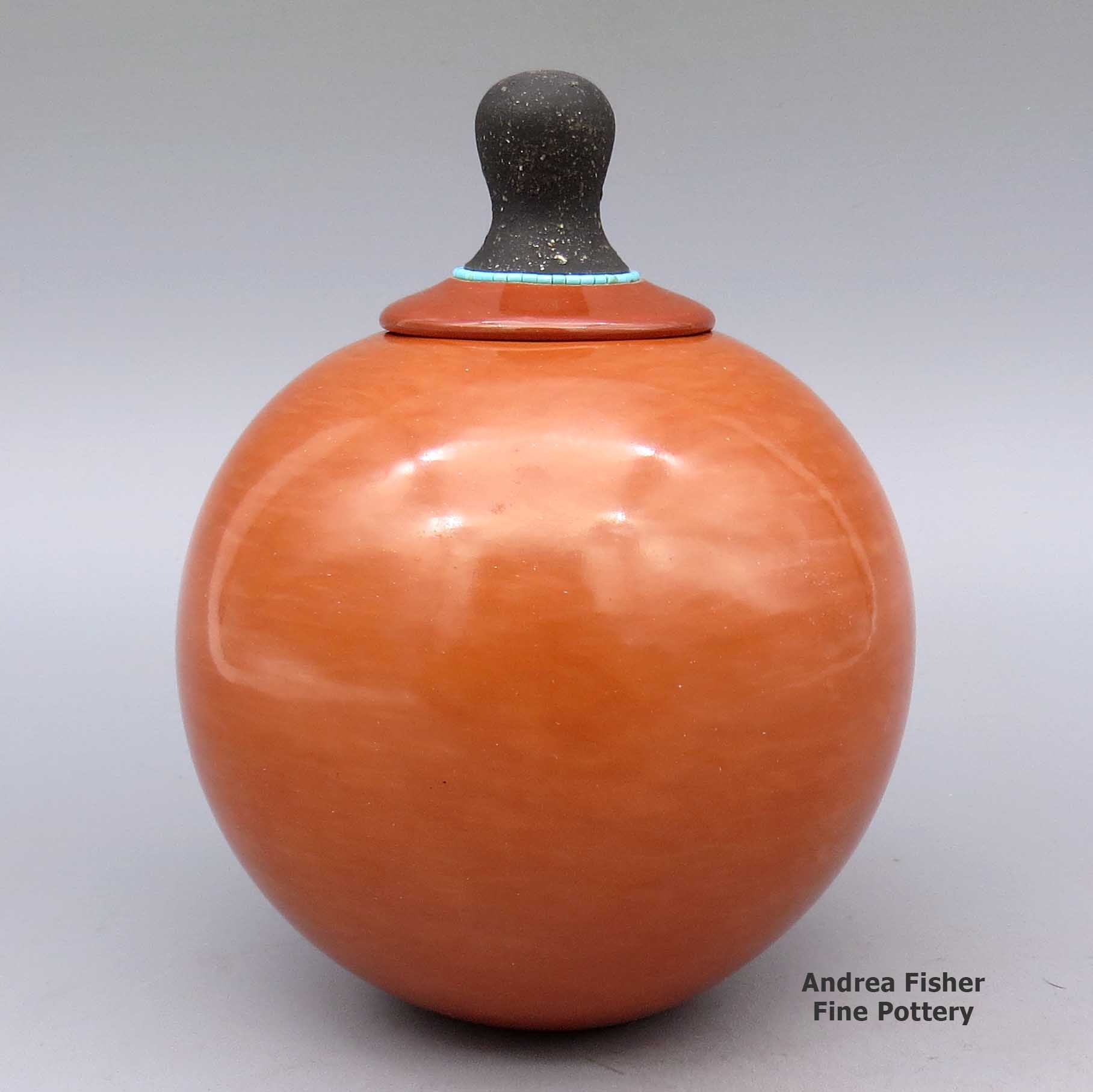

Russell Sanchez, lksi2l325: Polychrome lidded jar with geometric design

$2,900.00

A polychrome lidded jar with a sgraffito-and-carved lizard and geometric design plus micaceous black slip, inlaid turquoise heishi beads and a matching lid

In stock

Brand

Sanchez, Russell

When Russell was about 8, Rose began teaching him the traditional way to make pottery. He says that one day when he was 11 or 12 he put a batch of small, newly finished black-on-black pots outside and Anita Da (Popovi Da's widow) came by and took a look. Then she told him, "I want you to start bringing me stuff" and that's how his pottery career really began to take off.

After a while he also began working with Rose's daughter-in-law, Dora Tse-Pe. From Dora he learned how to refine his process and attain a more perfect product. Since then he has developed his own techniques and has often been referred to as a modernist potter.

Because he grew up speaking Tewa, Russell was able to converse with his tribal elders. Because he could speak to them in Tewa, they told him where to go and what to look for when he went out in search of clay deposits.

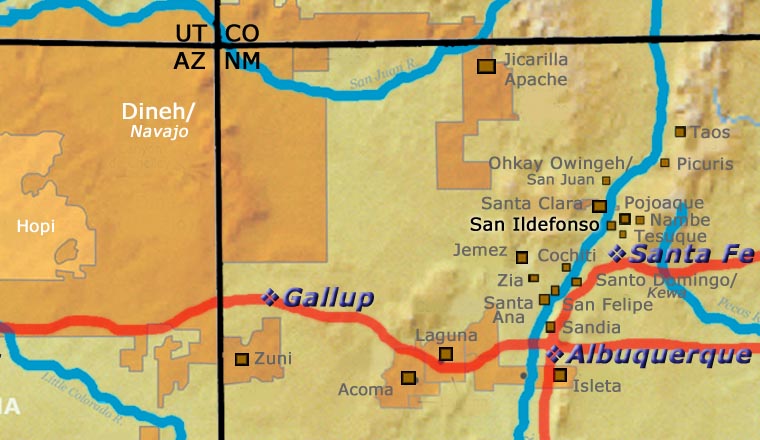

He found many of the old clay sources at San Ildefonso and has used them to help recreate many of the San Ildefonso styles from the 1800s. It was in the early 1900s that most San Ildefonso potters started creating black-on-black pottery.

Russell has done significant research into old styles and designs among the collections at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture and the School for Advanced Research. If you ask if he copies any of those he responds with a saying he learned in his youth: "This is mine, this is what I do. Take it and make it your own."

Russell is an avid outdoorsman and an expert with a kayak and a river raft. He's paddled rivers in Peru and Chile. He's challenged the Zambesi River in southern Africa. However, tamer rivers closer to home allow him to gather clay wherever he finds it.

That has led to experiments with many different types of clay, even to the point of incorporating two or more different colors of clay into the same pot.

He also often uses slips made of different colors of clay, including micaceous. His designs are painted, carved, incised and sometimes inlaid with turquoise and/or coral and strands of heishi beads.

For Russell, "traditional" doesn't mean being stuck in any one time period. It's more like growing and moving forward with everyone adding something else to the "traditional" as they travel their own paths.

Russell has earned many awards over the years, including several First and Second Place ribbons at the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show and the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market.

Collections of his work can be found at the Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, New Mexico, the Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles, the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC, the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico and the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona.

In 2017 Russell was awarded the 2017 New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts.

Some of the Awards Russell has Earned

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: "Black Sienna Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Figurative, native clay, hand built: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Red Bear Lidded Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Any design or form with non-native materials, includes kiln-fired pottery: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Black Gunmetal Water Jar"

- 2021 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice - Charles King. Awarded for artwork: "Red Bear Lidded Jar"

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, included ribbed, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery with Detached Lid

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Figurative, native clay, hand built: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Bear"

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques: Best of Division

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, any form: Second Place

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 804 - Painted, any form: First Place

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 805 - Figures, including sets: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques: Best of Division

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, Any Form: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 807 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market: Tony Da Memorial Award, “New Vision in Pueblo Pottery.” For Excellence in the Creative and Innovative Use of Traditional Materials and Techniques

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Dr. Arthur Pelberg. Awarded for artwork: Black Mica Polished Water Jar

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffito, any form: First Place

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using Native materials with or without added decorative elements, traditional firing techniques, Category 805 - Figures, including sets: First Place

- 2017 New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts. Note: public ceremony held September 15, 2017, at the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Classification II Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, Including Ribbed Native Clay, Hand Built, Fired Out-of-Doors: First Place. Awarded for Art Work: Old Style Black Water Jar

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place

- 2016 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with native materials: Second Place

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with native materials: Second Place with Jennifer Tafoya

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three inches at its greatest dimension: Second Place with Nancy Youngblood

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification with Jennifer Moquino

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place with Jennifer Moquino

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: Second Place

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: Second Place with Jennifer Moquino

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, figurative: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: Honorable Mention

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-Native materials: First Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-Native materials: Second Place

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - hand-built, figurative: First Place

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-Traditional Design or form with non-Native materials: Honorable Mention

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native clay, hand built, carved: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional - hand-built, figurative: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-Traditional Design or form with non-Native materials: First Place

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: First Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional - Native clay/hand built/carved/ribbed/incised: Second Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional -native clay/hand built, figurative effigies, canteens, plates, storytellers, nativity scenes: Second Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Non-traditional design or form with non-native materials: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1501 - Jars, Wedding Jars, and Vases: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1502 - Bowls: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-Traditional Pottery Using Traditional Materials and Techniques with Non-Traditional Decorative Elements, Category 1503 - Combined Techniques, Any Shaped Vessel: Second Place

- 1979 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Third Place. Awarded for artwork: Pottery

- 1978 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Seed pot

- 1978 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification X - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division HH - Pottery: Third Place. Awarded for artwork: Etched jar with turquoise

- 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division GG - Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: Wedding vase

- 1977 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts and Crafts Exhibit, Classification XI - Students - Grades 7 through 12, Division GG - Pottery: Honorable Mention. Awarded for artwork: Black bear with stone

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About the Mimbres Culture

The Mimbres culture existed in the Mimbres Valley of southern New Mexico from about 850 CE to about 1150 CE. They were a sub-culture of the greater Mogollon culture that extended from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre Mountains, north to the San Andres Mountains and northwest along the Mogollon Rim to the vicinity of today's Springerville, AZ.

North of the Gila Mountains was the influence of the Great Houses of the Chaco culture. Through comparisons of imagery and the colors used, it has been conjectured that Chaco was a more male dominant society while Mimbres was more female dominant. Both areas were settled, built, flowered and abandoned on almost exactly the same time schedules. But at the time of abandonment, the folks of Chaco mostly moved north while those of the Mimbres valley mostly went south.

The Mimbres people were among the first cultures that evolved their own forms of imagery and means of telling stories through those images. The Classic Mimbres period was the height of their creativity, from about 1000 CE to about 1150 CE. Then things changed and migrations began in earnest. Many moved south and brought some of their art to Paquimé. Others pushed north and then west, around the Gila Mountains. By 1200 CE the vast majority of the people in the area of the Mimbres Valley had moved elsewhere.

Most Mimbres pottery was black-on-white. Around 1120 CE there was an influx of migrants from Hohokam and Salado areas to the west. That's about when the first black-on-red pottery appeared in the Mimbres villages. Some of the imagery we see today from many of the Northern and Middle Rio Grande pueblos had its origins in the Mimbres Valley.

Substantial depopulation of the area occurred shortly after 1150 CE but there were many small surviving populations scattered around. Over time, these melted into the surrounding cultures with many families moving north to Acoma, Zuni and Hopi while others moved south to Casas Grande and Paquimé.

The greater Mogollon culture spanned the countryside from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre to Paquimé, then north through the Mimbres Valley to the edge of the White Sands and then northwest along the Mogollon Rim into east-central Arizona.

The time period from about 850 CE to about 1000 CE is classed the Late Basketmaker III period across the Southwest. The time period was characterized by the evolution of square and rectangular pithouses with plastered floors and walls. Ceremonial structures were generally dug deep into the ground. In the Mimbres Valley area, local forms of pottery have been classified as early Mimbres black-on-white (formerly Boldface Black-on-White), textured plainware and red-on-cream.

The Classic Mimbres phase (1000 CE to 1150 CE) was marked with the construction of larger buildings in clusters of communities around open plazas. Some constructions had up to 150 rooms. Most groupings of rooms included a ceremonial room, although smaller square or rectangular underground kivas with roof openings were also being used. Classic Mimbres settlements were located in areas with well-watered floodplains available, suitable for the growing of maize, squash and beans. The villages were limited in size by the ability of the local area to grow enough food to support the village.

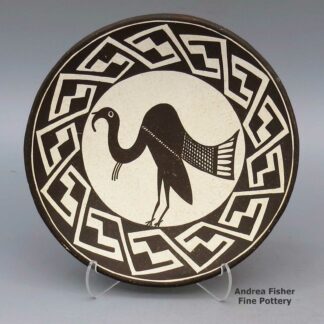

Pottery produced in the Mimbres region is distinct in style and decoration. Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery was primarily decorated with bold geometric designs, although some early pieces show human and animal figures. Over time the rendering of figurative and geometric designs grew more refined, sophisticated and diverse, suggesting community prosperity and a rich ceremonial life. Classic Mimbres black-on-white pottery is also characterized by bold geometric shapes executed with refined brushwork and very fine linework. Designs may include figures of one or more humans, animals or other shapes, bounded by either geometric decorations or by simple rim bands. A common figure on a Mimbres pot is the turkey, others are the thunderbird, rabbit and various anthropomorphic, half-human figures. There are also a lot of different fish depicted, some are species found only in the Gulf of California (hundreds of miles away across the desert).

A lot of Mimbres bowls (with kill holes) have been found in archaeological excavations but most Mimbres pottery shows evidence it was actually used in day-to-day life and wasn't produced just for burial purposes.

There's a lot of speculation as to what happened to the Mimbres people as their countryside was rapidly depopulated after about 1150 CE. The people of Isleta, Acoma and Laguna find ancient Mimbres pot shards on their pueblo lands, indicating that pottery designs from the Mimbres River area migrated north. There are similar designs found on pot shards littering the ground around Casas Grandes and Paquimé near Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. Other than where they went, the only reasons offered for why they left involve at least small scale climate change. The usual comment is "drought" but drought could have been brought on by the eruption of a volcano on the other side of the planet, or a small change in the El Nino-La Nina schedule. Whatever it was that started the outflow of people, it began in the Mimbres River area and spread outward from there. Excavations in the eastern Mimbres region (nearer to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico) have shown that the people adapted to new circumstances and that adaptation itself moved them closer into alignment with surrounding villages and cultures. Eventually they just kind of merged into the background population.

The groups that moved south and built up Paquimé and Casas Grandes became powerful and wealthy over the next couple hundred years. Then they seem to have lost a war in the mid-1400s and the survivors were forced to migrate to the west, to a land a bit more hospitable for them at the time. It's also quite possible that they were defeated by volcanic eruptions on the other side of the planet: the 1100s, 1200s and 1300s were a time of migration in many parts of the world because of continuing bad weather events. The Little Ice Age that saw temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere drop as much as 2°C began in the early 1300s and lasted into the mid 1800s. NASA feels that this was mostly a result of large volumes of volcanic aerosols being pumped into the atmosphere at the time.

Ramona Gonzales Family Tree - San Ildefonso Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Ramona Sanchez Gonzales (1885-), second wife of Juan Gonzales (painter)

- Rose (Cata) Gonzales (daughter-in-law)(1900-1989)(San Juan) & Robert Gonzales (1900-1935)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Andrea Tse Pe (1975-)

- Candace Tse-Pe (1968-)

- Gerri Tse-Pe (1963-)

- Irene Tse-Pe (1961-)

- Jennifer Tse-Pe (1966-1983)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (1940-2000) & Jennifer Tse Pe (Sisneros - second wife, Santa Clara)

- Marie Gonzales-Kailahi & James Kailahi

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Blue Corn (Crucita Gonzales Calabaza)(1921-1999)(step-daughter of Ramona) & Santiago Calabaza (Santo Domingo) (d. 1972)

- Heishi Flower (Diane Calabaza-Jenkins) (1955-)

- Joseph Calabaza (Tha Mo Thay)

- Elliott Calabaza

- Lucille Calabaza-King

- Nancy Calabaza

- Sophia Calabaza

- Stacey Calabaza

- Krieg Kalavaza

- Vera Solomon (Laguna)

Rose' students: - Juanita Gonzales (1909-1988) & Louis Wo-Peen Gonzales (brother of Rose Gonzales husband)

- Adelphia Martinez (1935- )

- Lorenzo Gonzales (1922-1995)(adopted by Louis & Juanita) & Delores Naquayoma (Hopi/Winnebago)

- Jeanne M. Gonzales (1959-)

- John Gonzales (1955-)

- Laurencita Gonzales

- Linda Gonzales

- Marie Ann Gonzales

- Raymond Gonzales

- Robert Gonzales (1947-) & Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-)

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Oqwa Pi (Abel Sanchez)(1899-1971) & Tomasena Cata Sanchez (Rose' sister) (1903-1985)

- Skipped generation

- Russell Sanchez (1966-)

- Skipped generation