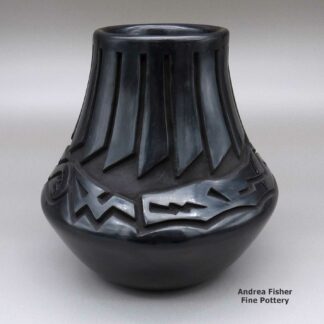

| Dimensions | 4.75 × 4.75 × 5.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has light scratches |

| Signature | Teresita Naranjo Santa Clara Pueblo |

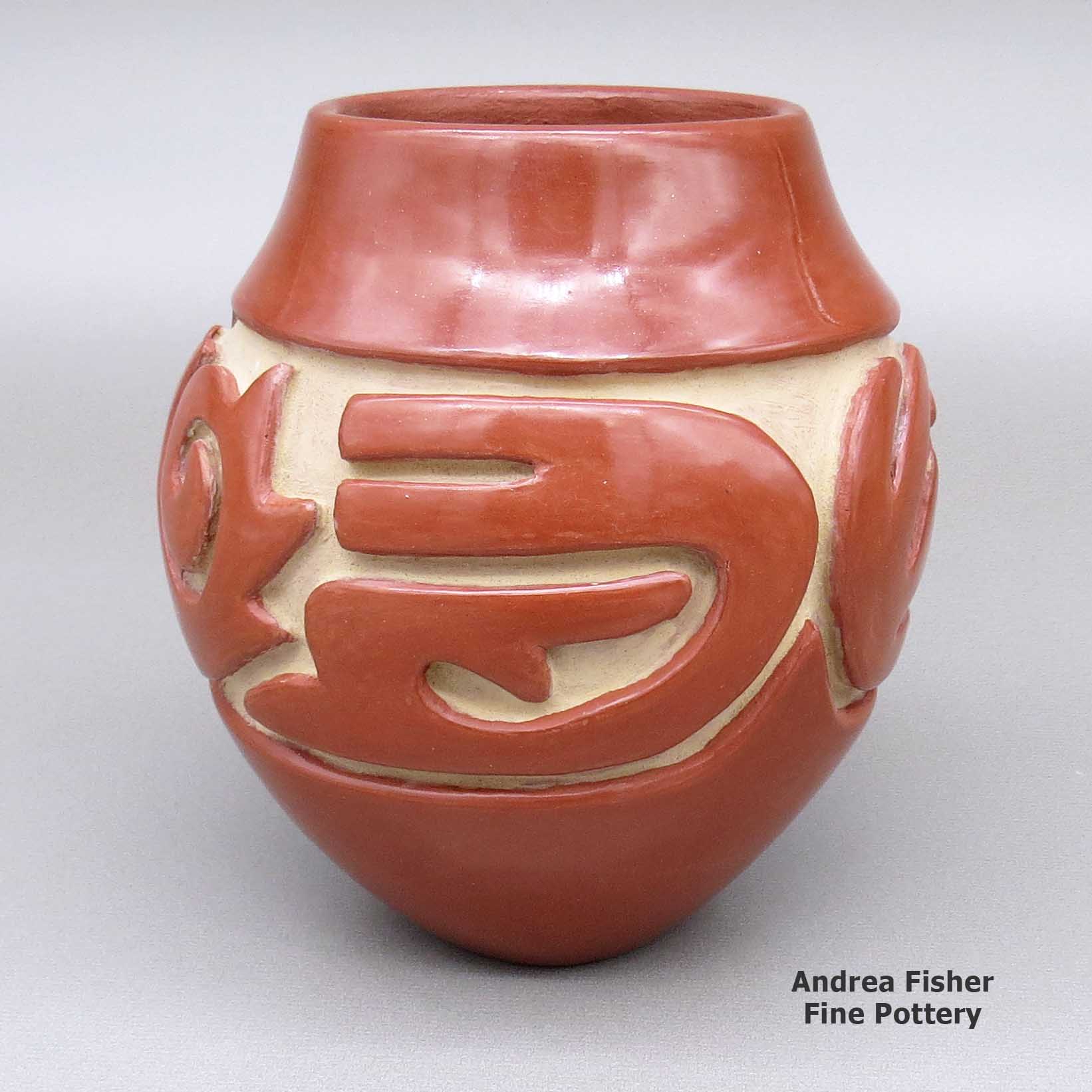

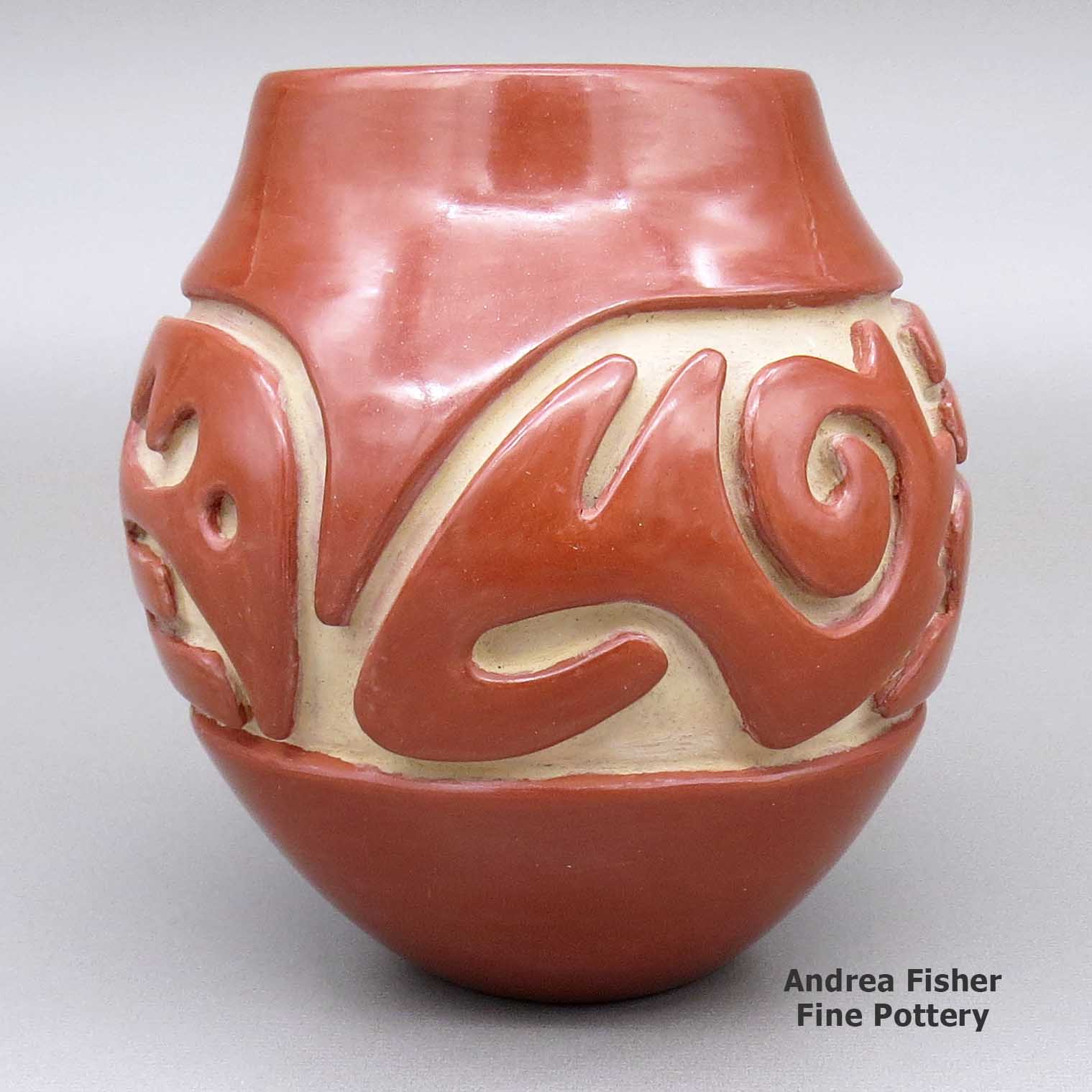

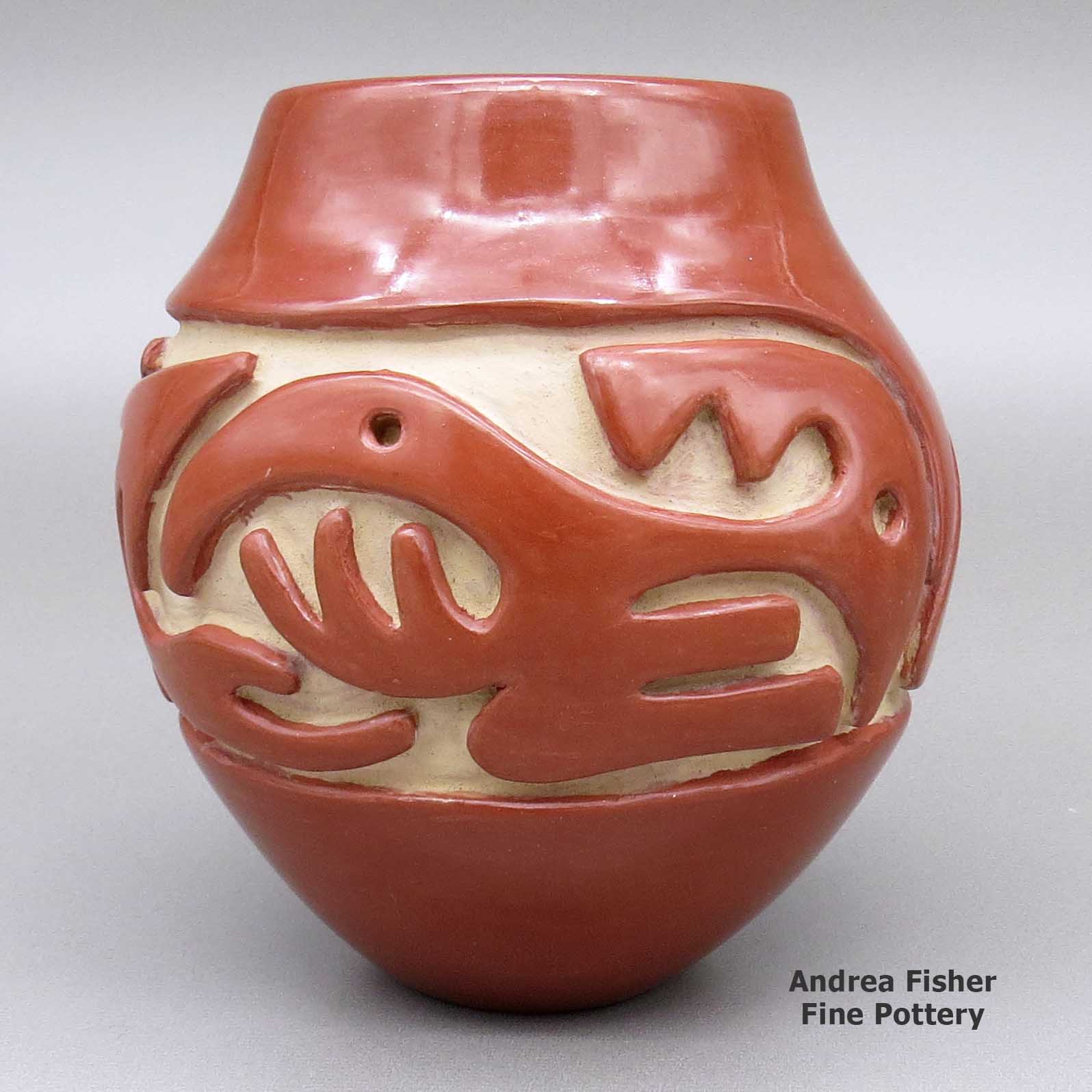

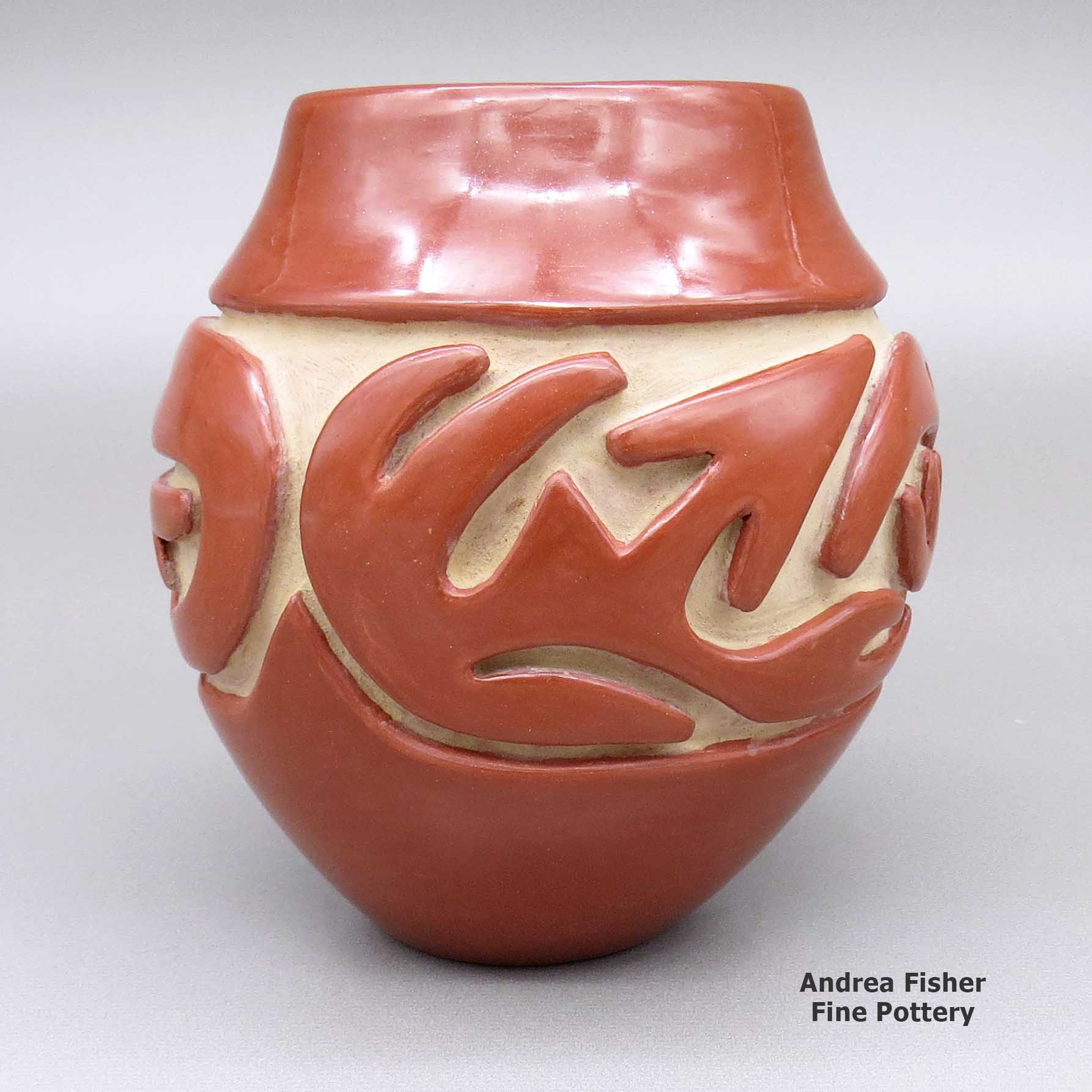

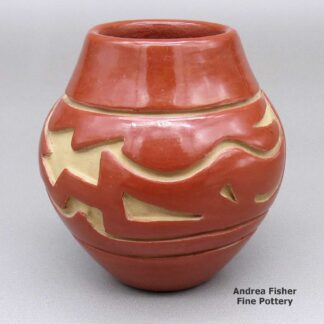

Teresita Naranjo, zzsc3b572, Red jar with a geometric design

$2,200.00

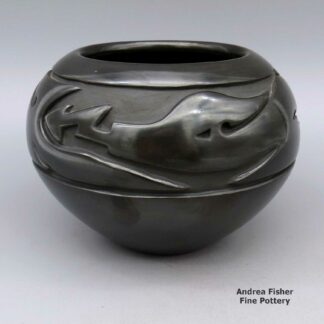

A red jar carved with a stylized avanyu and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Naranjo, Teresita

She married Joe Naranjo at an early age and they had four children. When the oldest was 12 her husband died and after that, she raised her family on her own, supported solely by her ability to make a living as a potter.

Teresita truly enjoyed making pottery. She excelled in creating carved redware and blackware bowls, wedding vases, jars and miniatures. Her favorite design to carve was the avanyu (the Tewa water serpent). She passed her skills and techniques on to her daughter, Stella Chavarria, who passed that learning on to her children in turn.

Teresita participated in shows at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology in 1974, the Popovi Da Studio of Indian Arts Gallery in 1976, the One Space/Three Visions exhibit at the Albuquerque Museum in 1979, the Sid Duesch Gallery show in New York City in 1985 and the Harris Collection show at Blue Rain Gallery in Taos, New Mexico in 1998. The Heard Museum in Phoenix also has a collection of her works on display.

Teresita passed on in 1999.

Some Exhibits that Featured Work by Teresita

- Gifts from the Community. Heard Museum West. Surprise, Arizona. April 2008 - October 12, 2008

- Choices and Change: American Indian Artists in the Southwest. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. 2007 June 2007 - June 2008

- Breaking the Surface: Carved Pottery Techniques and Designs. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. October 2004 - October 2005

- Hold Everything! Masterworks of Basketry and Pottery from the Heard Museum. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. November 1, 2001 - March 10, 2002

- Images, Artists, Styles: Recent Acquisitions from the Heard Museum Collection. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. July 2001 - July 2002

- Lovena Ohl: An Eye for Art, a Heart for Artists. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. January 15, 2000 - August 15, 2000

- From Cairo to Carefree: Building the Heard Museum. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. August 1997 - January 1998

- Recent Acquisitions from the Herman and Claire Bloom Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. January 1997 - July 1997

- The Seven Families of Pueblo Pottery. Simply Santa Fe. Santa Fe, NM. August 16, 1990 - August 31, 1990

- 18th Anniversary Show. Pacific Western Traders. Folsom, CA. September 9, 1989 - November 12, 1989

- Art of the Southwest. Pacific Western Traders. Folsom, CA. October 11, 1986 - November 16, 1986

- Tenth Anniversary (1971-1981). Pacific Western Traders. Folsom, CA. October 1, 1981 - December 31, 1981

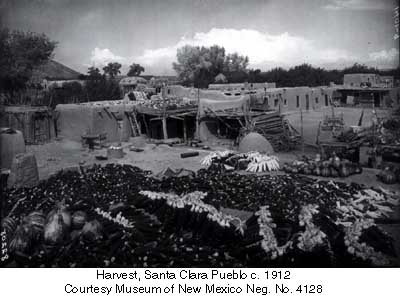

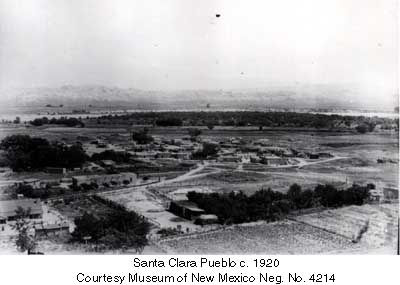

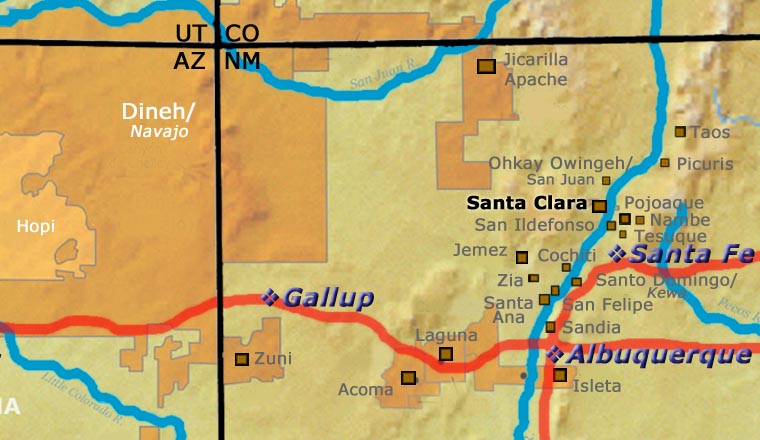

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

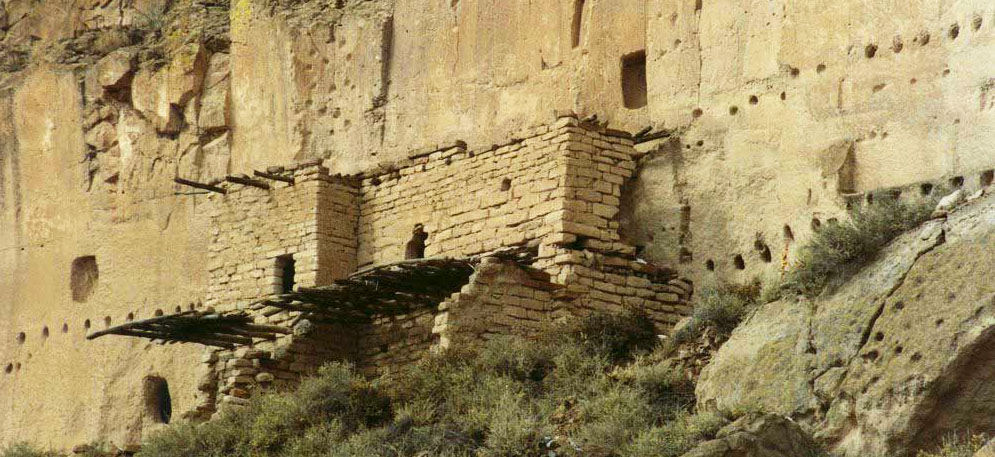

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About the Avanyu

The avanyu is a mythical water creature likened to the feathered and plumed serpents of Mesoamerica. The design is primarily part of the design palette of Tewa potters from the Tewa Basin, and even there it varies by pueblo and artist. Wherever the artist is, the avanyu design generally represents the spirit of water rushing through a village after a downpour. The avanyu is also seen as the Keeper of Springs and Guardian of Water. The image is a prayer for rain with the realization of what a downpour can do when it falls on the hard soil of the arid and semi-arid Southwestern deserts.

Artists from San Ildefonso Pueblo generally use an avanyu design with a three-plumed head while Santa Clara Pueblo potters generally use an avanyu with three feathers hanging off the head. The avanyu always has a forked tongue, signifying the lightning bolts that herald its arrival. Some have simplified the design to one feather or plume while others have stylized the design and almost made it cubic or Oriental in design and layout.

Hopi-Tewa potters generally use a somewhat similar Hopi version of a flying, feathered serpent named kwataka. The Zuni version is Kolowisi, although it has been determined that the power of Kolowisi is too much for anyone who is not of Zuni descent so depictions of it have gotten almost as rare as depictions of kwataka.

Christina Naranjo Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Christina Naranjo (1891-1980) & Jose Victor Naranjo (1895-1942)

- Mary Cain (1915-2010) & Willie Cain

- Billy Cain (1950-)

- Joy Cain (1947-)

- Linda Cain (1949-)

- Autumn Borts-Medlock (1967-)

- Tammy Garcia (1969-)

- Tina Diaz (1946-)

- Warren Cain (1951-)

- Douglas Tafoya

- Marjorie Tafoya Tanin

- Mary Louise Eckleberry (1921-2003)

- Darlene Eckleberry

- Victor (1958-) & Naomi Eckleberry

- Teresita Naranjo (1919-1999)

- Mildred Moore (Dineh, 1941-) & Victor Naranjo

- Eldon Moore

- Ernie Moore

- Kelli Moore

- Rick Moore

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Denise Chavarria (1959-)

- Joey Chavarria (1964-1987)

- Loretta Sunday Chavarria (Singer) (1963-)

- Mildred Moore (Dineh, 1941-) & Victor Naranjo

- Cecilia Naranjo & James Lee McLean

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Ira Atencio (1975-)

- Lawrence Thunder Atencio

- Judy Tafoya (1962-) & Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Cecilia Fawn Tafoya (1986-)

- Chelsea Tafoya

- Eli Tafoya (1991-)

- Josetta Tafoya (1993-)

- Lincoln A. Tafoya (1989-)

- Linette Tafoya (1989-)

- Sarah Ayla Tafoya (1987-)

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Mida Tafoya (1931-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Kimberly Garcia (1978-)

- Cookie Kathleen Tafoya (1963-)

- Robert Maurice "Moe" Tafoya

- Donna Tafoya (1952-)

- Mike Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis Tafoya (1955-) & Matthew Tafoya (1953-)

- Lorraine Tafoya

- Matthew Tafoya Jr.

- Sabina Tafoya

- Sherry Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis & Marlin Hemlock (Seneca)

- Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo and Gracie Naranjo (Dineh)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo Jr.

- Teresa Naranjo

- Tracy Naranjo