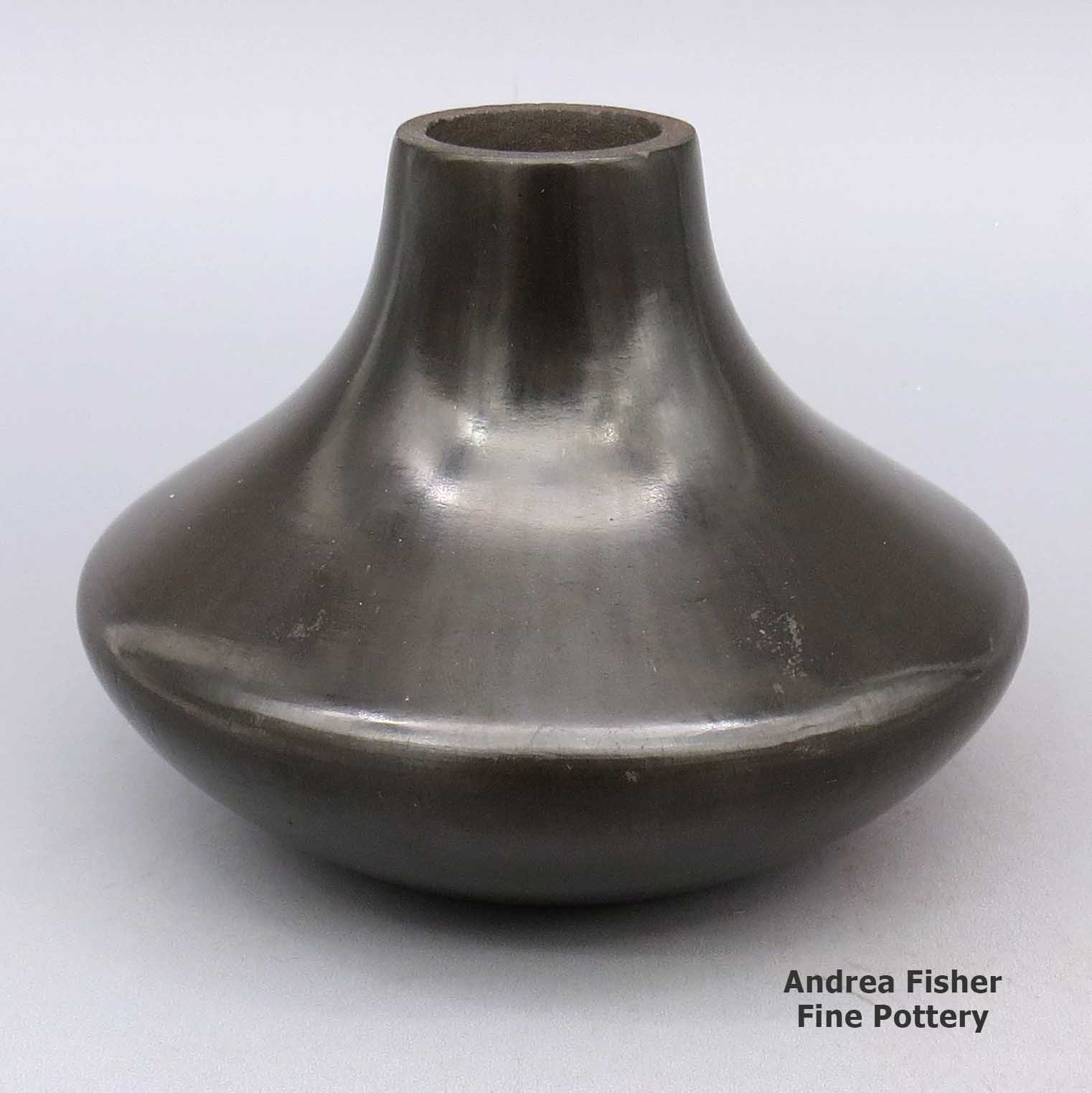

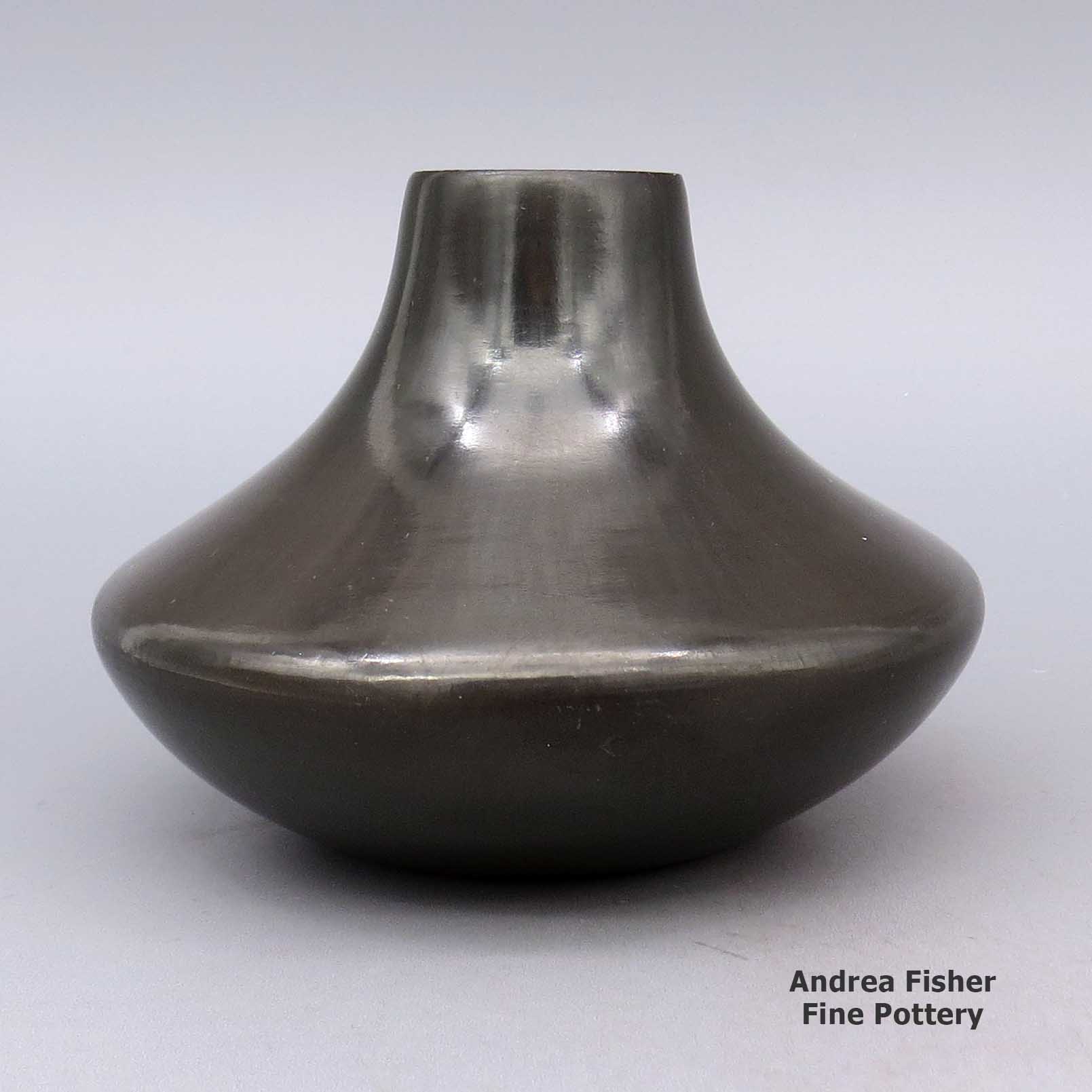

| Dimensions | 4.25 × 4.25 × 3.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has light scratches |

| Signature | TP |

Tse-Pe, lksi2l309: Plain black jar

$425.00

A highly polished and undecorated low-shouldered black jar

In stock

Brand

Tse-Pe

Tse-Pe learned how to make pottery while watching his mother as he was growing up. Originally from Ohkay Owingeh, Rose deep carved and incised her pieces while he learned to prefer sgraffito and low relief carving.

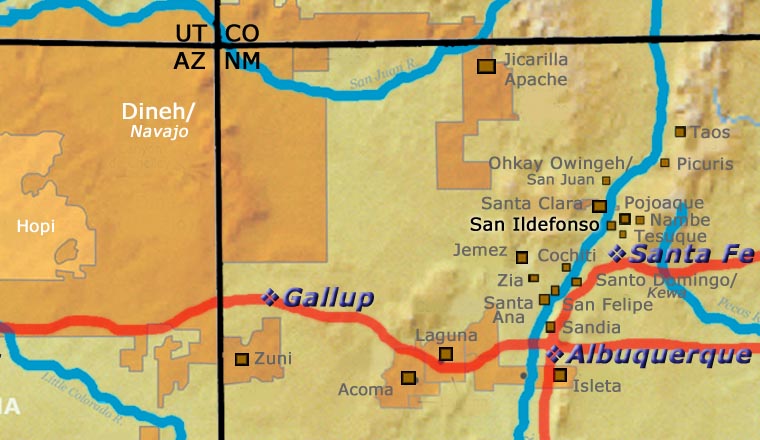

When he was 19, Tse-Pe married Dora Gachupin of Zia Pueblo. Contrary to Puebloan tradition, she moved to his home at San Ildefonso. She had learned the Zia way of making pottery from her mother, Candelaria Gachupin, as she grew up. At San Ildefonso she learned the San Ildefonso way of making pottery from her mother-in-law. Together, Tse-Pe and Dora were exposed to the works of Popovi Da and Tony Da from San Ildefonso and Joseph Lonewolf, Camilio Tafoya and Grace Medicine Flower from Santa Clara Pueblo. They all worked to push the quality of sgraffito work higher and higher.

Tse-Pe also added turquoise and heishe bead inlays and micaceous and green clays to his pottery, styles that were adopted and developed further by Russell Sanchez.

Tse-Pe and Dora divorced around 1979 and Dora went on to an award-earning career on her own. Tse-Pe met and married Jennifer Sisneros of Santa Clara soon after the divorce.

Tse-Pe always credited his mother with inspiring him to be a potter. His daughters, Andrea, Candace, Gerri, Irene and Jennifer, credited both their parents with inspiring them.

Some Awards earned by Tse-Pe

- 1976 Santa Fe Indian Market, Second Place award with Dora for an incised bowl

- 1978 Santa Fe Indian Market, Second Place award with Dora for a carved black jar

- 1978 Santa Fe Indian Market, Second Place award with Dora for a carved black jar with an avanyu design

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

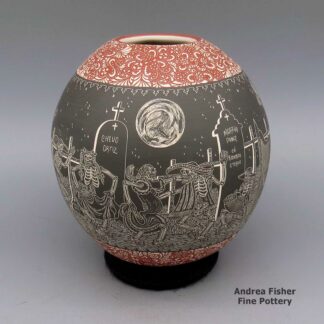

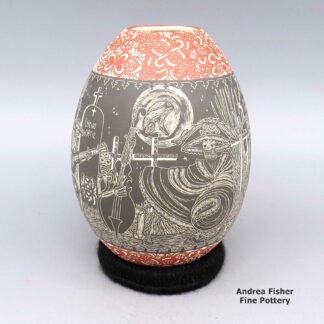

About Undecorated Pottery

In the very beginning, ceramics were rough creations with no designs on them. They were purely utilitarian and, over time, their creation was made smoother. Several hundred years later, some potters felt their product was good enough to support decorations. Then came the search for pigments that would survive the firing process. The first successful pieces were black designs on white/grey clay, the black derived from organic sources and turning black through firing in an oxygen-reduction atmosphere. However, even fifteen hundred years after the first pots may have been decorated with carbon-based organic paint in the Southwest, some pueblo potters still produce undecorated polished wares.

For some, it is enough to smooth their pieces, then slip them with a finely ground mix of micaceous clay and water before firing. For others, their pots need to be polished extremely smooth, then fired to be their final color (usually red or black). The only embellishments the piece might have are organic openings, flared rims, tall necks, low shoulders, double-shoulders or triple-shoulders, all of which are built in during the coiling process.

Ramona Gonzales Family Tree - San Ildefonso Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Ramona Sanchez Gonzales (1885-), second wife of Juan Gonzales (painter)

- Rose (Cata) Gonzales (daughter-in-law)(1900-1989)(San Juan) & Robert Gonzales (1900-1935)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Andrea Tse Pe (1975-)

- Candace Tse-Pe (1968-)

- Gerri Tse-Pe (1963-)

- Irene Tse-Pe (1961-)

- Jennifer Tse-Pe (1966-1983)

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (1940-2000) & Jennifer Tse Pe (Sisneros - second wife, Santa Clara)

- Marie Gonzales-Kailahi & James Kailahi

- (Johnnie) Tse-Pe (Gonzales)(1940-2000) & Dora Tse-Pe (Gachupin, first wife, Zia, 1939-)

- Blue Corn (Crucita Gonzales Calabaza)(1921-1999)(step-daughter of Ramona) & Santiago Calabaza (Santo Domingo) (d. 1972)

- Heishi Flower (Diane Calabaza-Jenkins) (1955-)

- Joseph Calabaza (Tha Mo Thay)

- Elliott Calabaza

- Lucille Calabaza-King

- Nancy Calabaza

- Sophia Calabaza

- Stacey Calabaza

- Krieg Kalavaza

- Vera Solomon (Laguna)

Rose' students: - Juanita Gonzales (1909-1988) & Louis Wo-Peen Gonzales (brother of Rose Gonzales husband)

- Adelphia Martinez (1935- )

- Lorenzo Gonzales (1922-1995)(adopted by Louis & Juanita) & Delores Naquayoma (Hopi/Winnebago)

- Jeanne M. Gonzales (1959-)

- John Gonzales (1955-)

- Laurencita Gonzales

- Linda Gonzales

- Marie Ann Gonzales

- Raymond Gonzales

- Robert Gonzales (1947-) & Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-)

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Oqwa Pi (Abel Sanchez)(1899-1971) & Tomasena Cata Sanchez (Rose' sister) (1903-1985)

- Skipped generation

- Russell Sanchez (1966-)

- Skipped generation