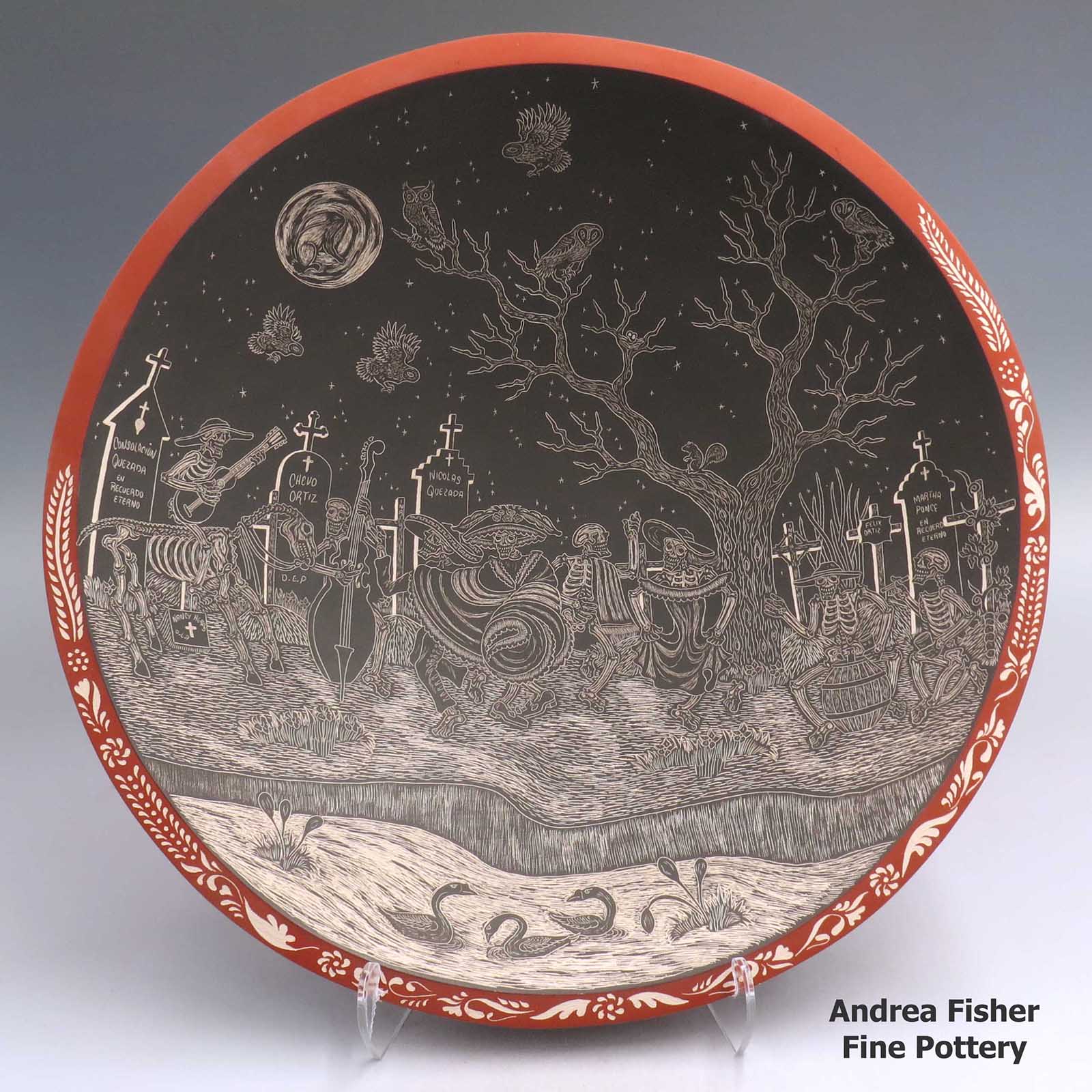

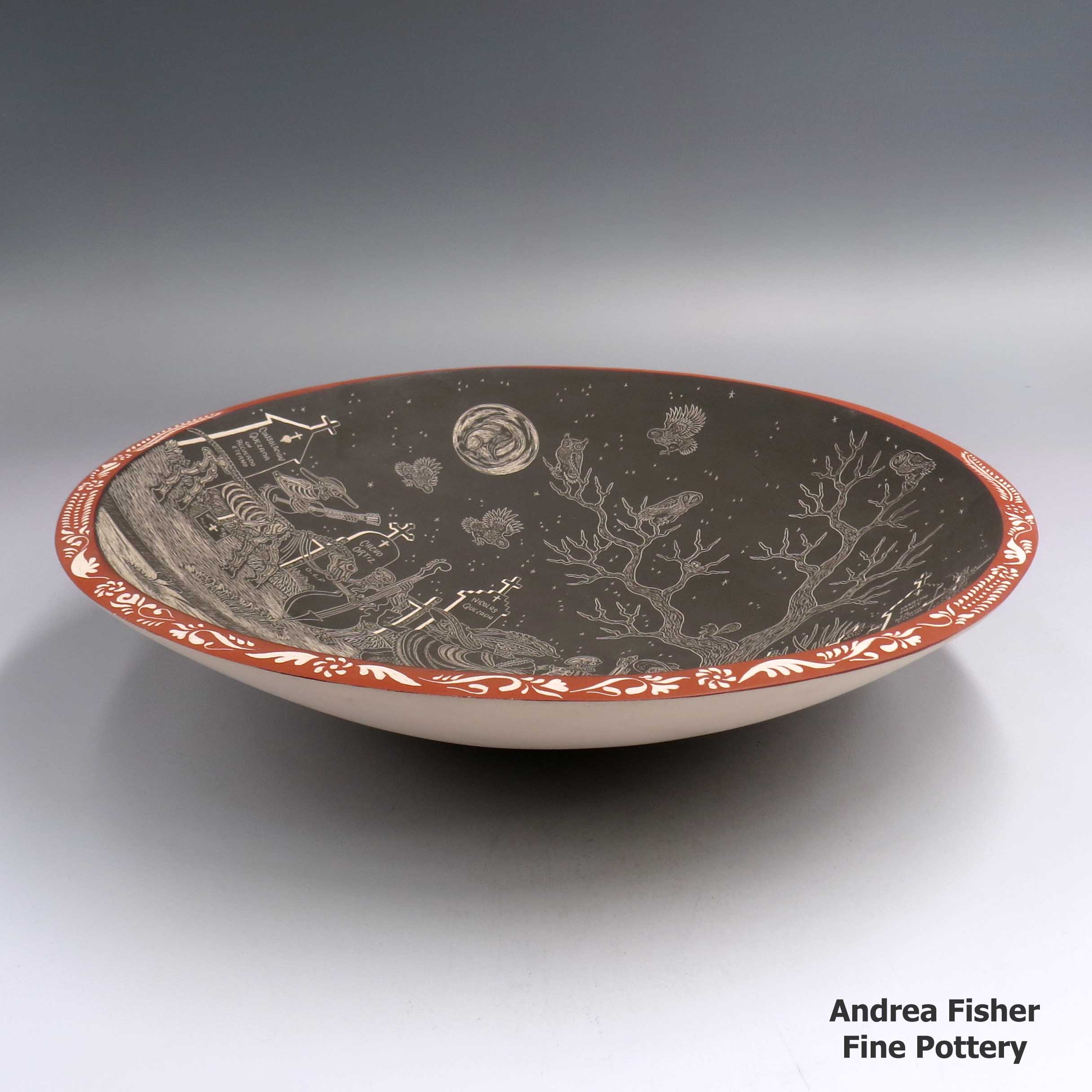

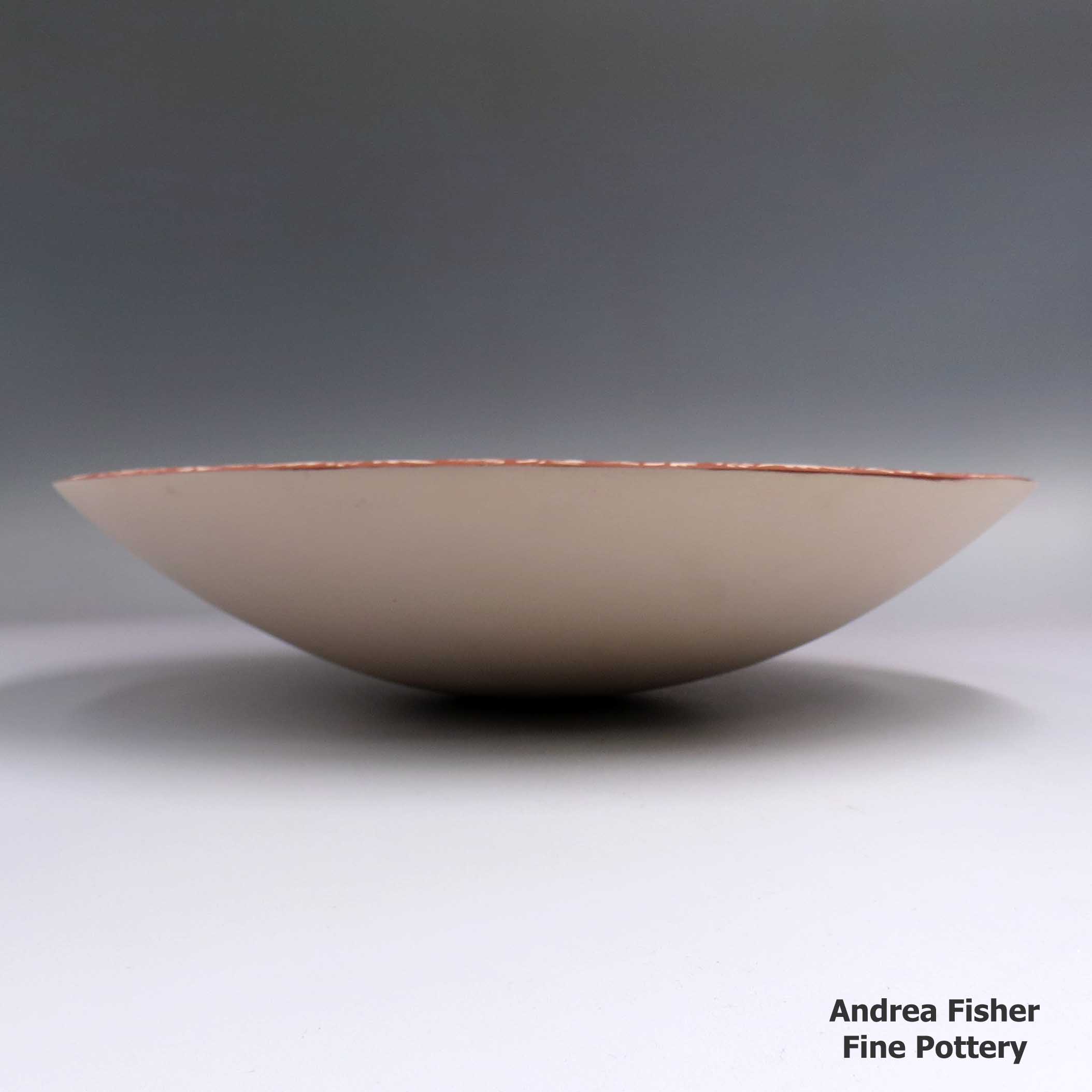

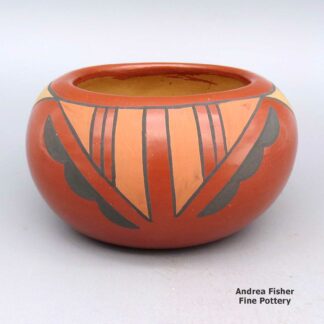

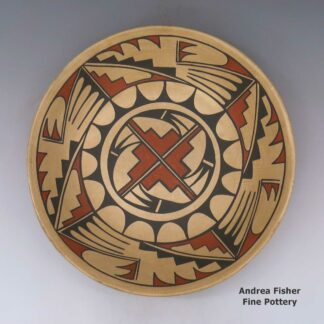

| Dimensions | 12.25 × 12.25 × 2.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Signature | H. Javier Martinez Mendez Gabriela Perez de Martinez |

| Date Born | 2021 |

Hector Javier Martinez, zzcg1m257m5, Bowl with Night of the Dead design

$1,500.00

A shallow polychrome bowl decorated with a sgraffito Night of the Dead at the Cemetery under a Full Moon design

In stock

Brand

Martinez, Hector Javier

"Time for something different." - The best advice Javier says he ever got, from Steve Rose

"Time for something different." - The best advice Javier says he ever got, from Steve RoseBorn in 1984, Hector Javier Martinez sprang onto the Mata Ortiz pottery scene around 2008 with his distinctive style of black and tan pots incised with Day of the Dead and Night of the Dead motifs. Those designs resulted from a comment made to him by Steve Rose (a well-known American pottery dealer). Employed as an auto mechanic and gardener just to make ends meet while he figured out the pottery making business, Javier had asked what Steve thought he needed to do in order to make pottery his permanent vocation. Steve replied, "Time for something different."

A few years later Javier earned a First Place ribbon in the 2013 Concurso Ceramica Juan Mata Ortiz for one of his Day of the Dead pots. In 2014 he earned the Presidencial Award at the Premio Nacional de la Ceramica in Tlaquepaque, Mexico, for a large olla incised with Mexico City views and his Night of the Dead theme. Since then we have seen his pots with Day of the Dead and Night of the Dead motifs on them with backgrounds from Paris, Santa Fe, Mata Ortiz, Venice, Italy, and New York City.

Javier told us he first learned to make pottery from his mother but her style was very different from what he found in Mata Ortiz. He had to learn all over again, using local materials and different processes and tools.

When he first began decorating his pots his subjects were religious (the Virgin of Guadalupe, priestly images, etc.) and the designs were all painted. It was in 2008 that he and his wife, Gabriela Perez de Martinez produced their first black and white sgraffito Day of the Dead/Night of the Dead pots together. The style took off immediately and they haven't looked back since, although they have branched out a bit and now produce bowls and plates, too.

Today, Javier is producing all kinds and sizes of pots with his signature Day of the Dead and Night of the Dead motifs. However, with his success has come competition and knockoffs. That said, the detail of his work sets him well apart and working with Gabriela has introduced some new elements into their Dia de los Muertos collection of designs.

Javier and Gabriela have four sons now (and Javier says he wants another). He says his inspiration comes from his culture and music. Gabriela concurred with that saying that when he's working on a large pot, he might as well be living as a character on the pot.

In 2020, Hector Javier earned the First Place ribbon for sgraffito design at the annual Concurso Ceramica de Mata Ortiz.

About Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes

Mata Ortiz is a small settlement inside the bounds of the Casas Grandes municipality, very near the site of Paquimé. The fortunes of the town have gone up and down over the years with a real economic slump happening after the local railroad repair yard was relocated to Nuevo Casas Grandes in the early 1960s. It was a village with a past and little future.

A problem around the ancient sites has been the looting of ancient pottery. From the 1950s on, someone could dig up an old pot, clean it up a bit and sell it to an American dealer (and those were everywhere) for more money than they'd make in a month with a regular job. And there's always been a shortage of regular jobs.

Many of the earliest potters in Mata Ortiz began learning to make pots when it started getting harder to find true ancient pots. So their first experiments turned out crude pottery but with a little work, their pots could be "antiqued" enough to pass muster as being ancient. Over a few years each modern potter got better and better until finally, their work could hardly be distinguished from the truly ancient. Then the Mexican Antiquities Act was passed and terror struck: because the old and the new could not be differentiated, potters were having all their property seized and their families put out of their homes because of "antiqued" pottery they made just yesterday. Things had to change almost overnight and several potters destroyed large amounts of their own inventory because it looked "antique." Then they went about rebooting the process and the product in Mata Ortiz.

For more info:

Mata Ortiz pottery at Wikipedia

Mata Ortiz at Wikipedia

Casas Grandes at Wikipedia

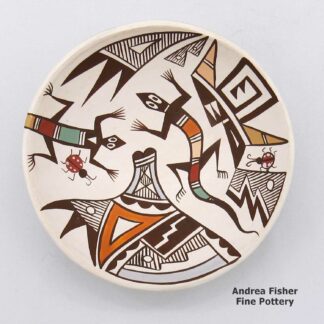

Contemporary Pottery

The term "contemporary" has several possible shadings in reference to Southwestern pottery. At some pueblos, it's more an indicator of a modern style of carving or etching than anything else. At San Felipe it refers to almost anything newly made there as they have almost no prehistoric templates to work from. At Jemez the situation resolved to where what makes a piece uniquely "Jemez" is the clay. Any designs on that clay can be said to be "contemporary."

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

Day/Night of the Dead

The Day of the Dead, El Dia de los Muertos, is a holiday celebrated in Mexico. Ancient rituals from central and southern Mexico, going back more than 2,500 years, are merged with Catholic beliefs brought by the Spanish in the 1500s. The holiday is about honoring the ancestors with food, drink, parties and other activities designed to include the ancestors' spirits in today's daily life. Families also set up ofrendas (private altars) to honor their ancestors.

Death is considered an integral part of the continuum of life and is not to be feared. Celebrations occur November 1 (All Saints Day) when adult spirits come to visit. On November 2 (All Souls Day), families go to the cemetery to decorate the graves of their loved ones. This is a very colorful holiday with marigolds, cardboard skeletons, sugar skulls, incense and tissue paper decorations in riotous colors everywhere.

Depictions of Day of the Dead (and Night of the Dead) activities is a motif explored by several renowned potters from the village of Mata Ortiz in the State of Chihuahua, in northern Mexico. Premier among them is Hector Javier Martinez who originated the style in 2008 after searching for "something different" to help him support his family simply through making and selling his own pottery. Hector has since earned several major awards for his Day of the Dead (and Night of the Dead) pottery. The very prestigious Presidencial Award from the Mexican Concurso Ceramica Nacional in Tlaquepaque is one of them.

Alfredo Rodriguez, Diana Loya, Martin Corona, Adrian Corona and Emiliano Rodriguez are some of the other Mata Ortiz artists using Day of the Dead and Night of the Dead motifs as inspiration for their own creations.