| Dimensions | 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Signature | Marvin and Frances Martinez San Ildefonso |

| Date Born | 2023 |

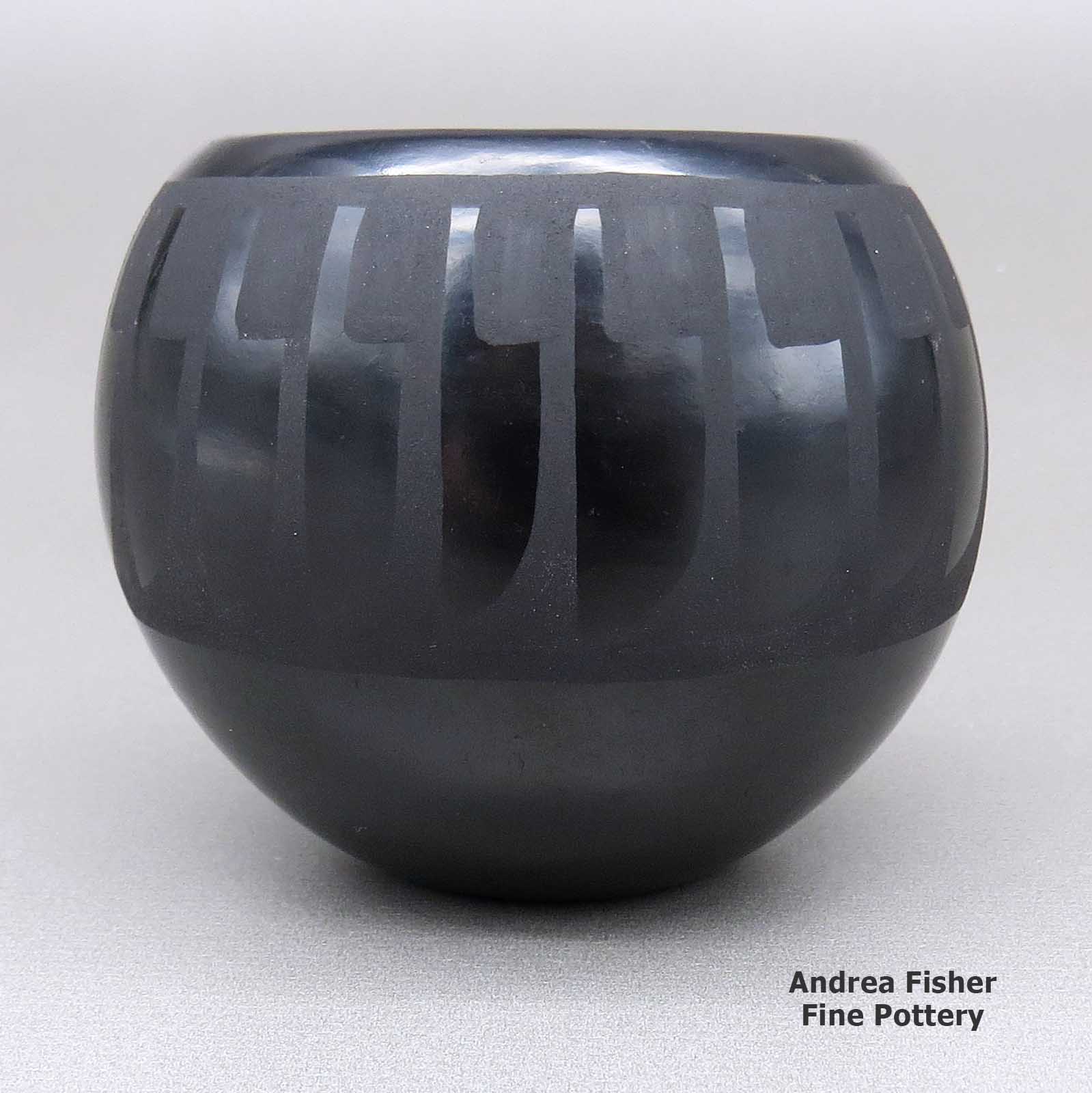

Marvin and Frances Martinez, zzsi3b082m4, Bowl with a geometric design

$225.00

A small black-on-black bowl decorated with a band-of-feathers geometric design

In stock

Brand

Martinez, Marvin and Frances

In 1964 Marvin Martinez was born into the internationally renowned family of Maria Martinez, the famous potter of San Ildefonso Pueblo. He is Maria's great-grandson, grandson of Adam and Santana Martinez. His wife Frances is from Santa Clara Pueblo and they have three children.

In 1964 Marvin Martinez was born into the internationally renowned family of Maria Martinez, the famous potter of San Ildefonso Pueblo. He is Maria's great-grandson, grandson of Adam and Santana Martinez. His wife Frances is from Santa Clara Pueblo and they have three children.Marvin and Frances create their pieces in the traditional way using clay gathered from pueblo land and hand-processed at home. They then hand-coil their pots, stone polish them, decorate them with designs in bee-weed and then fire their pots outdoors. Their favorite design is the avanyu (water serpent) which Marvin occasionally varies by adding rain coming down from the clouds in the avanyu design, as well as altering the teeth of the serpent.

It was Marvin’s great-grandfather, Julian, who started painting the avanyu design. It was Julian who also invented the matte black paint that made half of the black-on-black style back around 1918.

Marvin spent his childhood around potters and says, "I have memories of helping my grandparents, Adam and Santana, get supplies for firing pottery. I watched them make pots and paint them. I also traveled with them to Idyllwild [Arts Summer Program at the Idyllwild Arts Academy in California] in 1974."

This exposure to great artistry has given Marvin a deep appreciation for the now traditional designs begun by his family. "I would like for everyone to enjoy our pottery and give it a good home because we respect our clay, because it comes from Mother Earth, and we pray for good health for the whole world, and for all to live in peace and harmony," he states.

They sign their work: "Marvin & Frances Martinez, San Ildefonso".

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

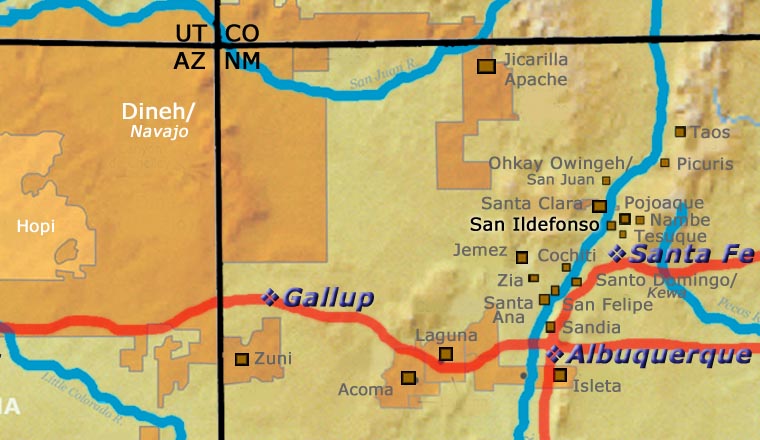

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Bird Elements

One of the main tenets of the Flower World ideology is that birds are messengers to and from Paradise. They carry our prayers to Heaven and they bring back the responses. Not all the pueblos accepted the Flower World ideology but it seems almost everyone, almost everywhere, agrees that birds are the messengers of Heaven. All pueblos do have multiple designs that incorporate feathers, if feathers aren't the main element of the design.

The Flower World ideology originated in central Mexico and most likely traveled north to the pueblos in the company of missionaries and long-distance traders. Turquoise was taken south while tropical birds, copper bells, seashells, and textiles (with particular spiritual designs on them), along with other spiritual items, were taken north. Going either way, almost everyone passed by Paquimé. The trade routes from the south came together there and the trade routes to the north diverged from there. That business didn't really come together until the first structures went up in the immediate vicinity of Paquimé, around 1150 CE. Then it ended around 1450 CE when the city was abandoned. That was also the end of pilgrims making their way south and then coming north again a few years later. For more than 300 years that traffic had been a major profit center and prestige generator for the people of Paquimé and Casas Grandes. After Paquimé was abandoned, though, the trade and pilrimage routes became far more dangerous. With the advent of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico, being a foreigner in that area became far more dangerous, too. Essentially, the puebloans who had embraced the Flower World ideology were cut off from their Holy Land.

The Flower World Complex, with its symbology, flowed across the American Southwest and eventually reached the Four Corners area. But it arrived at about the same time the kachina cults were coming together and the people were abandoning the Four Corners. The Flower World ideology was felt to be greater than what had come before so it's symbology was basically imprinted on top of that. Then the designs of the kachina cults and other clans were added on top of the Flower World symbology. Then came the Europeans with their designs and spiritual practices.

One of the principals of Native American design is that it is necessary only to note one part of most animals to imply the presence of the whole, especially when it comes to birds and bird elements. A lot of the design on Hopi pottery can only be described as "bird elements," although it is often possible to discern parrot feathers from eagle feathers, and eagletails from other bird's tails.

The Zunis have an ancient "almost-spiral" design that comes from the beaks of their equally ancient "rainbirds." The Zunis also like to make owl figures as owls are a symbol of wisdom to them. To some Northern Tewas, owls are creatures to be feared.

At Acoma they have a "cloudeater," a crane pictured with neck bent over and filling with fish shown sideways in its throat as it swallows them whole. Acoma potters also have a parrot that resembles the parrot found on the sides of the boxes carried by Amish traders back in the day. The parrot is not complete without a branch with leaves, and maybe berries, in its claws.

At Santo Domingo, religious dictates limit what can be imaged on pottery offered to the public. Birds, fish, turtles and flowers are allowed, along with a vast catalog of geometric designs. Images of humans are not. Next door at Cochiti, almost anything goes

The artists of the Mata Ortiz area are resurrecting some of the designs left behind by artists of old but they have no inner connection with the Flower World. Others in today's Mata Ortiz have gone totally contemporary: carving, scratching and painting beautiful images of birds with branches, vines and flowers.

Maria Martinez Family Tree - San Ildefonso Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Reyes Peña (d. 1909) & Tomas Montoya (d. 1914)

- Maria Montoya Martinez (1887-1980) & Julian Martinez (1884-1943)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) & Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Anita Martinez (d. 1992) & Pino Martinez

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Kathy Wan Povi Sanchez (1950-) & Gilbert Sanchez (San Juan)

- Corrine Sanchez

- Gilbert Abel Sanchez

- Liana Sanchez

- Wayland Sanchez

- Evelyn Than-Povi Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Berlinda Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Peter Pino

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Viola Martinez/Sunset Cruz & Johnnie Cruz Sr.

- Beverly Martinez (1960-1987)

- Marvin Martinez (1964-) & Frances Martinez

- Johnnie Cruz Jr. (1975-)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Popovi Da (1921-1971) & Anita Da

- Tony Da (1940-2008)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) & Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- Desideria Montoya (1889-1982)

- Maximiliana Montoya (1885-1955) & Cresencio Martinez (1879-1918)

- Juanita Vigil (1898-1933) & Romando Vigil (1902-1978)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Erik Fender (1970-)

- Gloria Maxey (d. 1999)

- Angelina Maxey (1970-)

- Jessie Maxey (1972-)

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Carmelita Vigil Dunlap (1925-1999) & Carlos Dunlap (d. 1971)

- Carlos Sunrise Dunlap (1958-1981)

- Cynthia Star Flower Dunlap (1959-)

- Jeannie Mountain Flower Dunlap (1953-)

- Linda Dunlap (1955-)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Maria Montoya Martinez (1887-1980) & Julian Martinez (1884-1943)