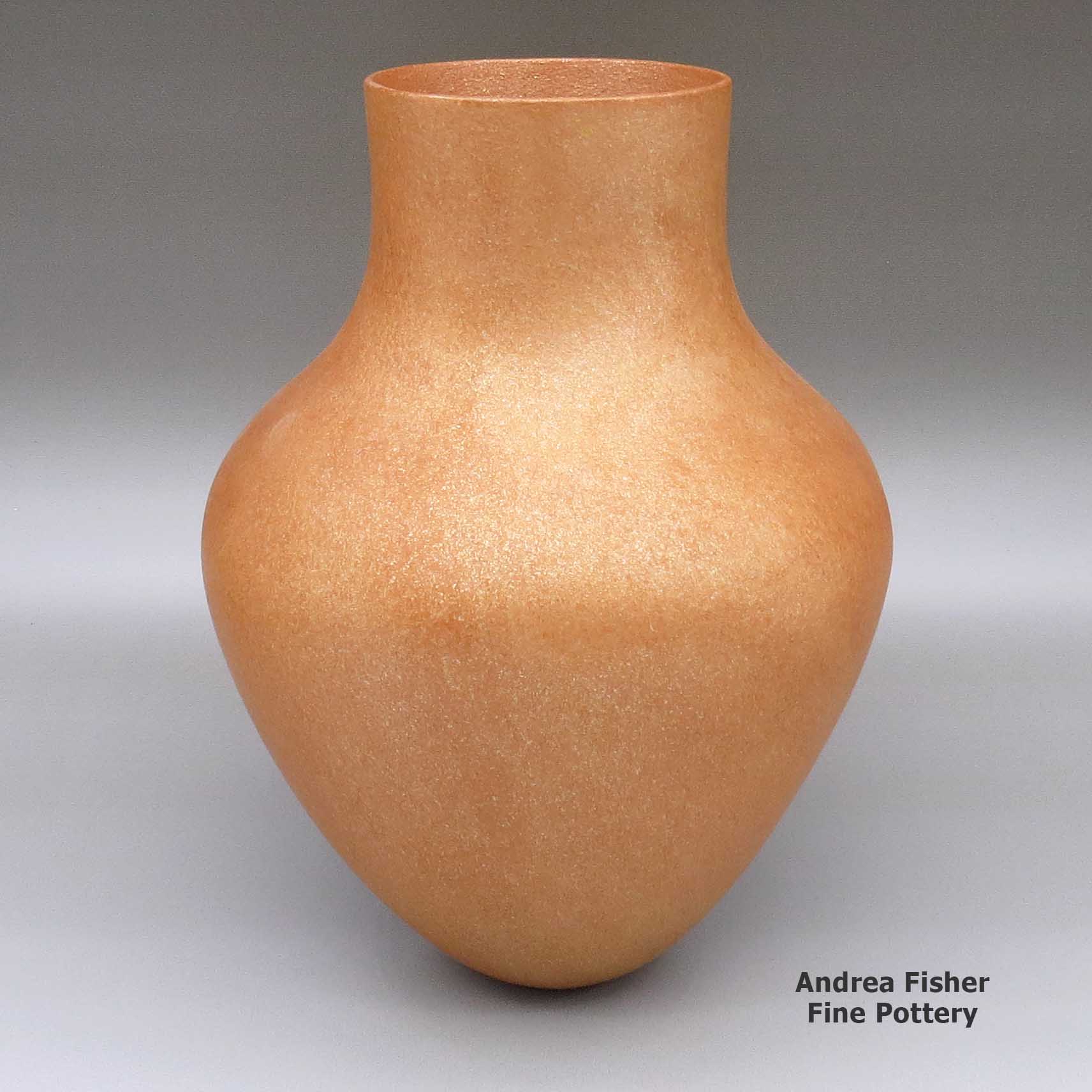

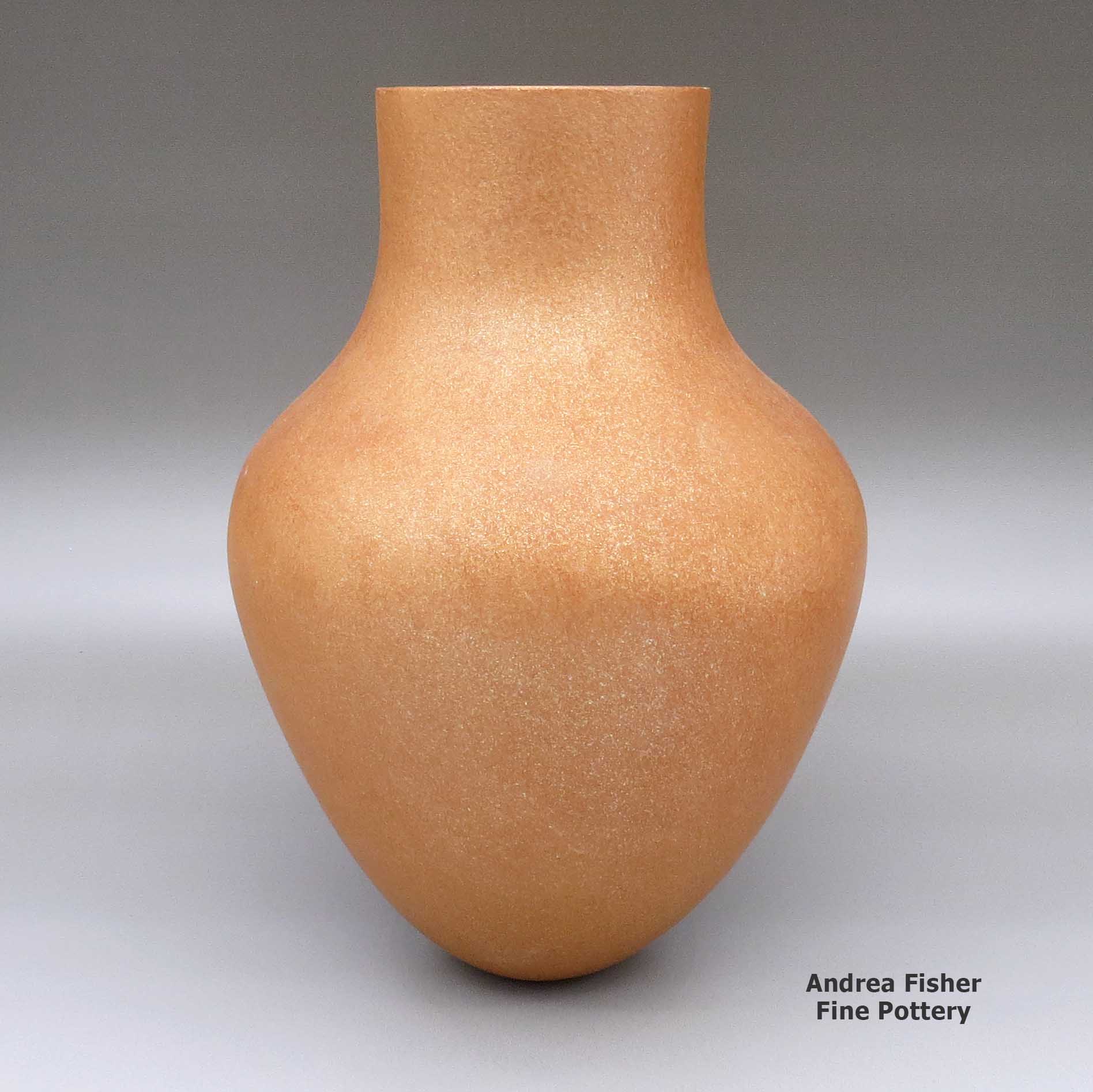

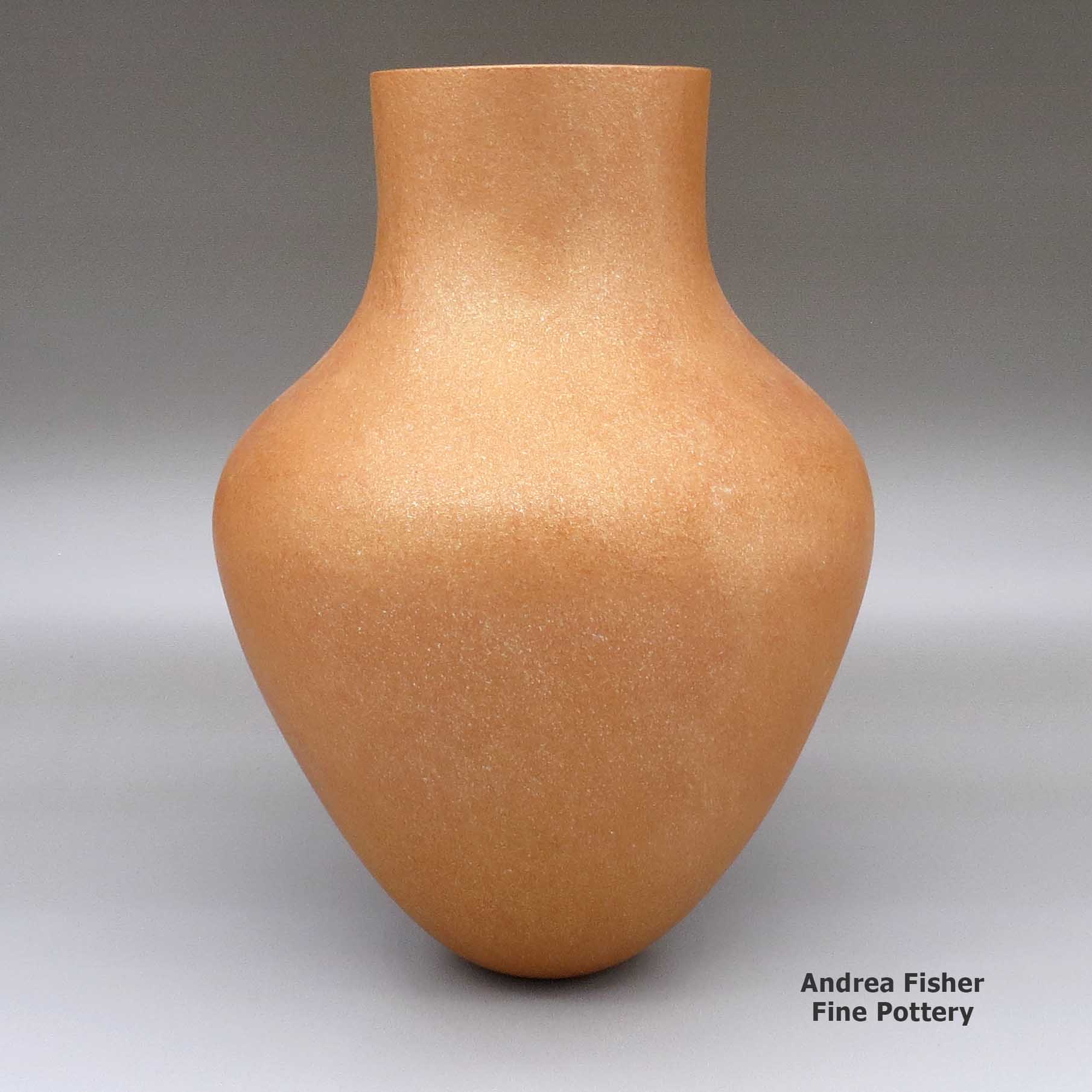

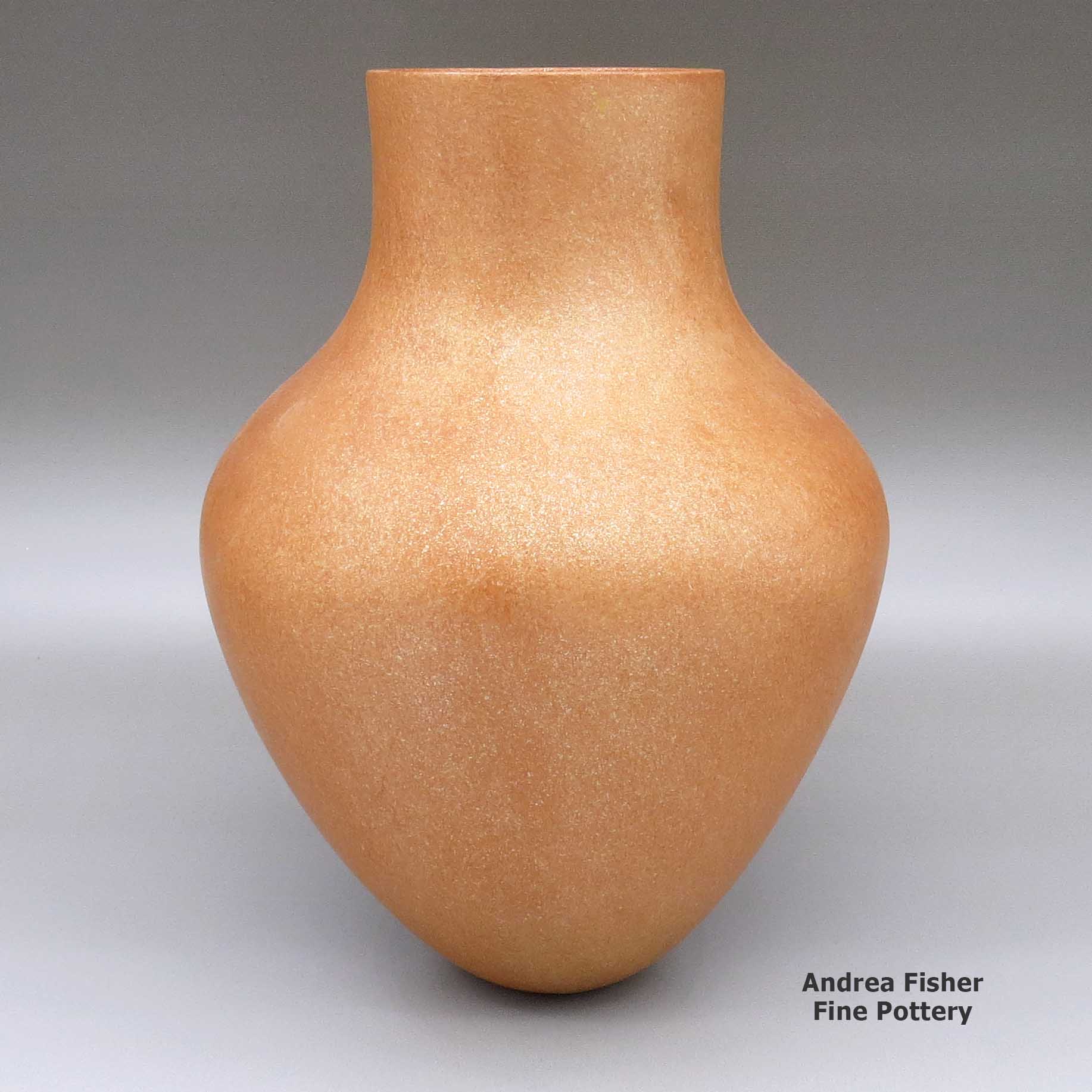

| Dimensions | 9.75 × 9.75 × 17.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, wear on bottom |

| Signature | Hubert Candelario San Felipe New Mexico |

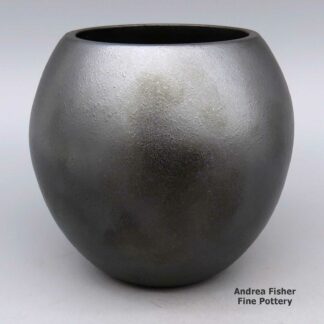

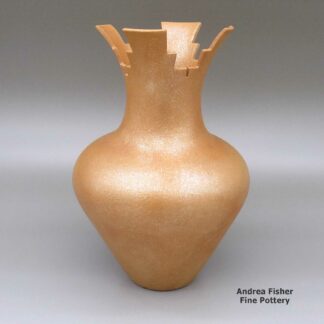

Hubert Candelario, thsf3b023, Golden micaceous jar

$1,995.00

A golden micaceous jar

In stock

Brand

Candelario, Hubert

Hubert Candelario (Butterfly) was born into San Felipe Pueblo in 1965. He's been actively making pottery since 1987.

Hubert Candelario (Butterfly) was born into San Felipe Pueblo in 1965. He's been actively making pottery since 1987.There was a time in the 1600s when San Felipe was an active pottery center but that ended with the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. San Felipe, Santo Domingo and Cochiti potters had been using leaded ores found in the Cerrillos Hills to decorate their pottery with and make the decorations last longer. They built a tremendous business with it but when the Spanish returned after the 1680 Revolt, they claimed all the lead deposits for themselves and that ended the making of pottery at San Felipe. After that San Felipe residents obtained their pottery in trade from neighbors, most often from Zia Pueblo.

Hubert earned an Associate's Degree in Architectural Design and Drafting. That fostered his appreciation for structure and pure architectural form. He credits Maria Martinez as being a major influence in his pottery career. He also says Santa Clara potter Nancy Youngblood has had a direct impact on his work with her carved, multi-ribbed melon jars.

Hubert's early works were traditional polished redware. Today he is famous for his contemporary, precisely carved puzzle pots, melon jars and pots perforated with circular or hexagonal holes.

The base structure of his pottery is formed using a red clay local to San Felipe. He completes the concept with layers of orange micaceous slip, burnished after each layer, to create his fabulous color and texture. The micaceous clay he gets from Nambe and Picuris Pueblos. He fires his pottery in a kiln to achieve an even color, free of fire clouds.

Hubert has earned numerous awards including more than one First Place ribbon at the Santa Fe Indian Market. His work was included in the 2002 exhibit and catalog Changing Hands: Art without Reservation at the American Craft Museum in New York City. One of his large swirl-cut melon jars was also selected for the permanent collection at the Denver Art Museum. Recently he earned a First Place ribbon for Miscellaneous pottery at Santa Fe Indian Market in 2019.

Hubert signs his work: "Hubert Candelario, San Felipe Pueblo", generally followed by the date the piece was made.

Some Exhibits that featured pieces by Hubert

- Breaking the Mold. Denver Art Museum. October 7, 2006 - August 19, 2007

- Breaking the Surface: Carved Pottery Techniques and Designs. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. October 2004 - October 2005

- Indian Market: New Directions in Southwestern Native American Pottery. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, Massachusetts. November 16, 2001 - March 17, 2002

- Exhibition of New Works. Gallery 10. Scottsdale, Arizona. March 28, 1996

Some Awards earned by Hubert

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Category 905, Miscellaneous, First Place

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Innovation Award for Pottery. Awarded for artwork: Oval Pot with Hole with Lid with Holes

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Category 905 - Contemporary pottery, any form or design, using commercial clays/glazes, all firing techniques - Miscellaneous: Second Place

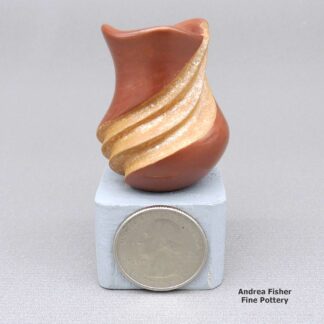

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II-G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: "Mini or Small Pot Flowing"

- 2019 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Jeremy Frey. Awarded for artwork: "Mica 9 Dragonfly Pot with Holes"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Miniature pots, individual pieces under 3 inches in any dimension: Best of Division

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-F - Miniature pots, individual pieces under 3 inches in any dimension, Category 1002 - Contemporary: First Place

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Fist Place. Awarded for artwork: "Starmelon Mica Mini"

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Contemporary Pottery, any form or design, using commercial clays/glazes, all firing techniques, Category 905 - Miscellaneous: Honorable Mention

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market. Classification II Pottery, Division E - Any Design or Form with Native Materials, Kiln Fired Pottery: Second Place. Awarded for Artwork: Mica Spirit Bowl

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional materials and techniques, any form or design, Category 1403 - Ribbed jars, wedding jars, vases and bowls, First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Non-traditional pottery, using traditional materials and techniques, any form or design, Category 1411 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division K - Pottery miniatures, 3" or less in height or diameter, Category 1704 - Non-traditional forms or designs: First Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, Category 1505 -Jars and vessels: Third Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - non-traditional, Category 1505 - Jars: First Place

- 1997 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1507 - Bowls: Third Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1603 - Jars and vases: First Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market. Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional, Category 1604 - Bowls: Third Place

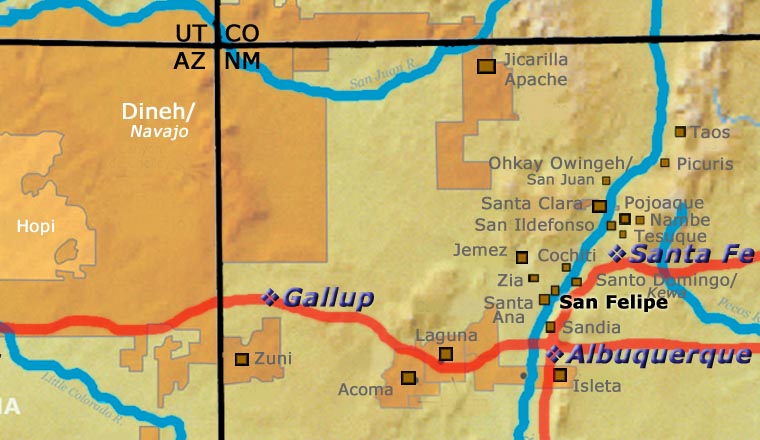

A Short History of San Felipe Pueblo

During the great migrations from the Four Corners area to what are now the Rio Grande Pueblos, the people of Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe were one. Before descending off the Pajarito Plateau to the Rio Grande, they settled in the area now known as Bandelier National Monument, taking advantage of a volcanic ash landscape that made it easy to construct dwellings. However, over time that area got too dry, too, and the people decided to move closer to the large river. Disagreements over where to settle split the people into what are now the Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe Pueblos.

When Francisco de Coronado arrived in 1540, there were two San Felipe villages, one on either side of the Rio Grande. The main villages were comprised of large two-and-three-story structures plus a couple hundred outlying dwellings. Coronado didn't stay long, there was no gold to be had. He and his men quickly moved on to Pecos Pueblo.

San Felipe was left alone until Don Juan de Oñaté came north in 1598. Then the troubles began. The Spanish built their first mission church next to the east village around 1600. It was built with conscript Indian labor and paid for by taxes extracted from the village. As more Spanish settlers moved into the area, that situation got worse.

The people of San Felipe participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 but killed no Spaniards or any priests. Governor Otermin returned with troops in 1681 and found San Felipe abandoned as the people had hidden themselves atop nearby Horn Mesa. The Spaniards looted and burned the pueblo before returning to Mexico. When Don Diego de Vargas came back in 1692, the people chose to surrender and be baptized rather than fight. To test the peace they first settled atop nearby Santa Ana Mesa. A few years later they descended into the Rio Grande Valley and founded today's pueblo.

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad built their main line along the Rio Grande, crossing Santo Domingo, San Felipe, Santa Ana, Sandia and Isleta land before reaching the Belen Cutoff area in the 1880s. Stations were built along the line next to each of those pueblos. That would have brought tourists to San Felipe but that was discouraged by the elders and there wasn't much to see anyway. Today's AmTrak and New Mexico RailRunner follow some of those same tracks.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Contemporary Pottery

The term "contemporary" has several possible shadings in reference to Southwestern pottery. At some pueblos, it's more an indicator of a modern style of carving or etching than anything else. At San Felipe it refers to almost anything newly made there as they have almost no prehistoric templates to work from. At Jemez the situation resolved to where what makes a piece uniquely "Jemez" is the clay. Any designs on that clay can be said to be "contemporary."

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.