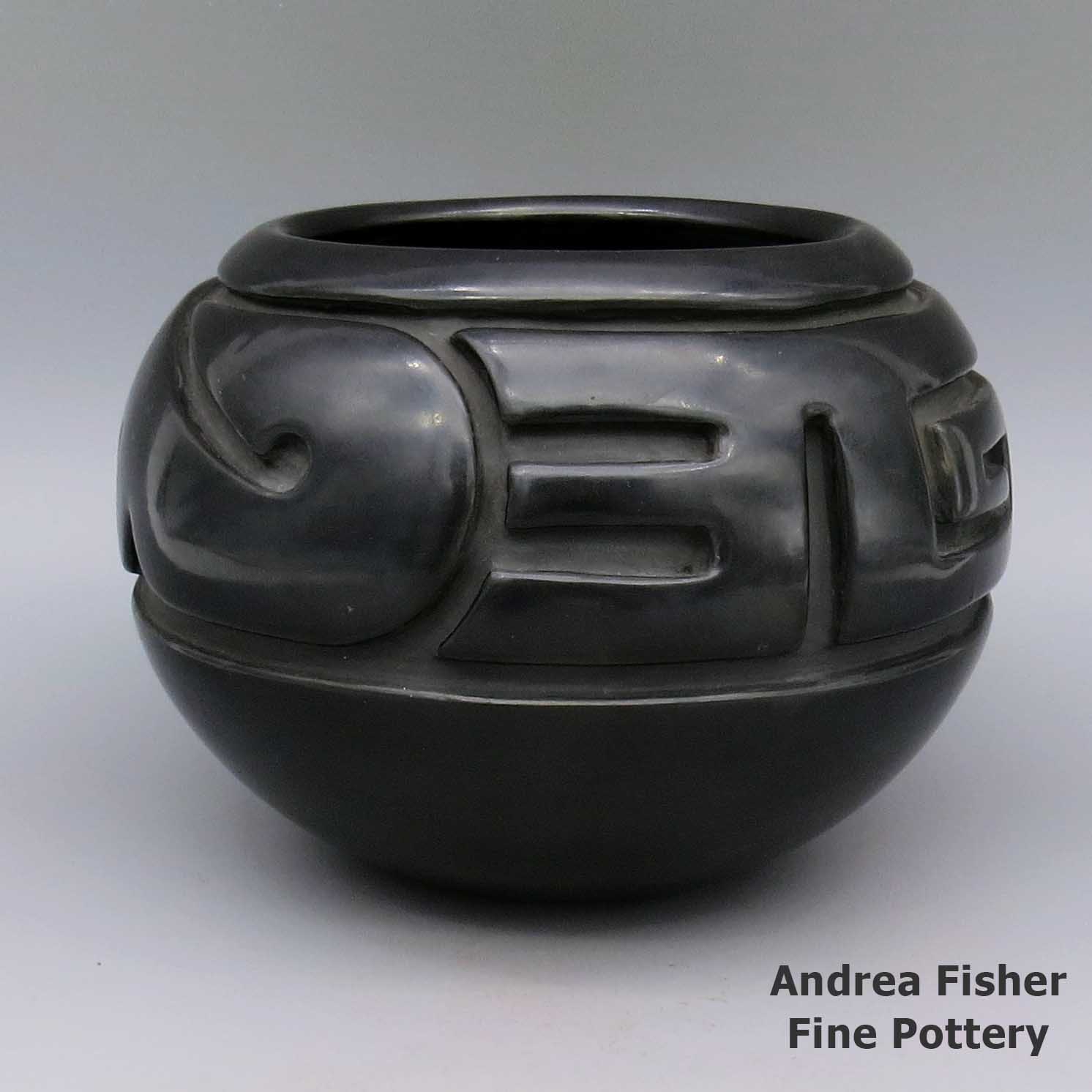

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 8.5 × 6 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Margaret Tafoya Santa Clara Pue |

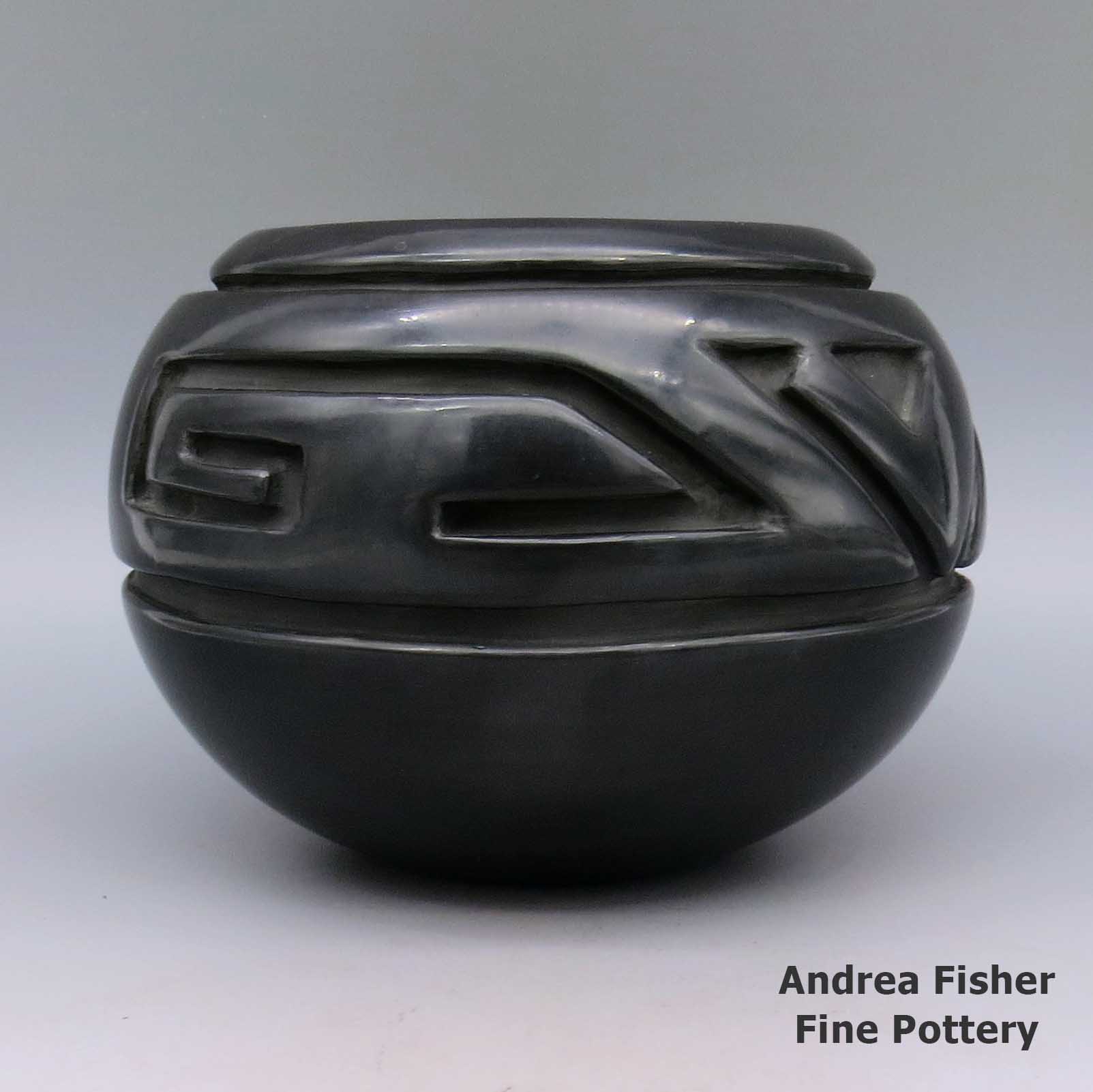

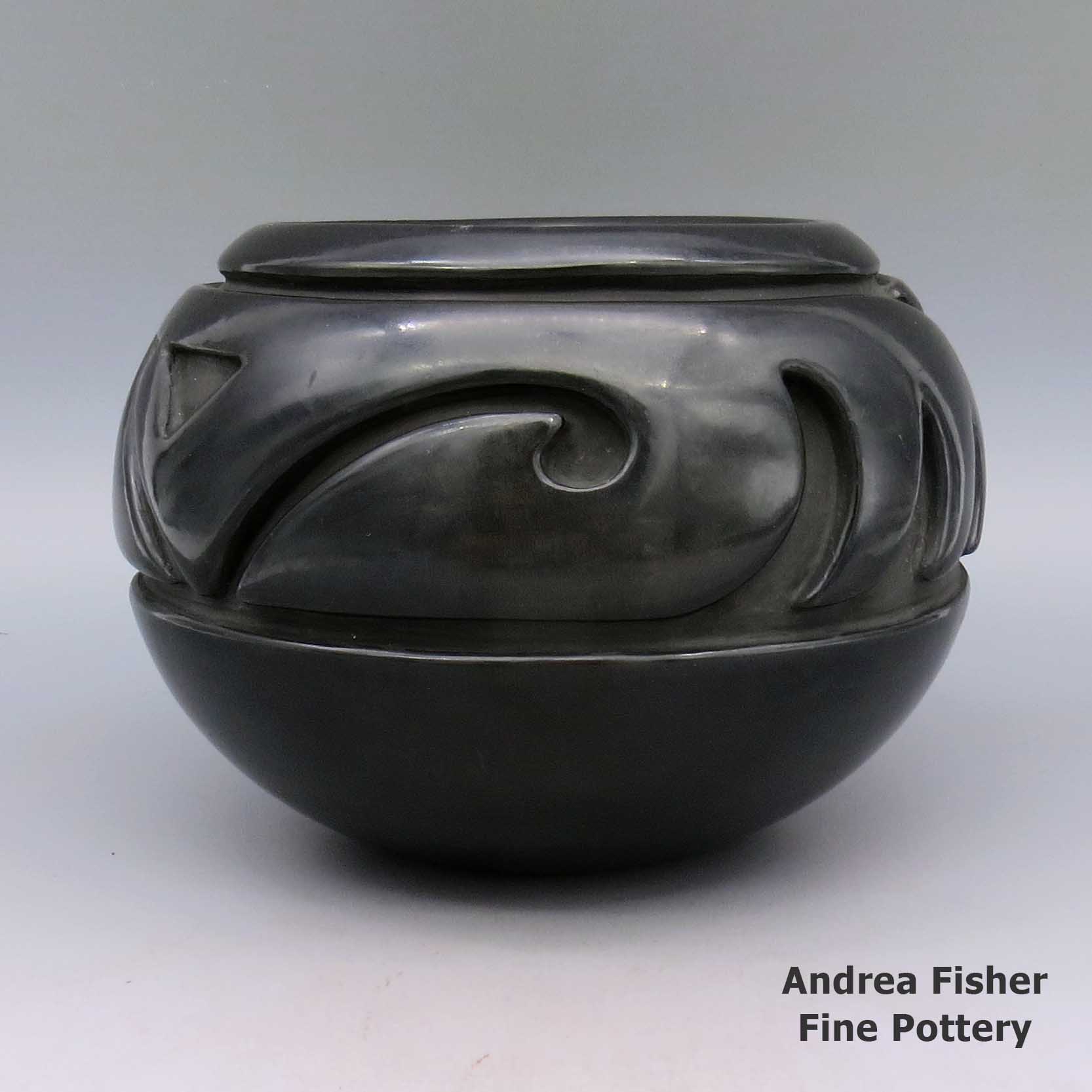

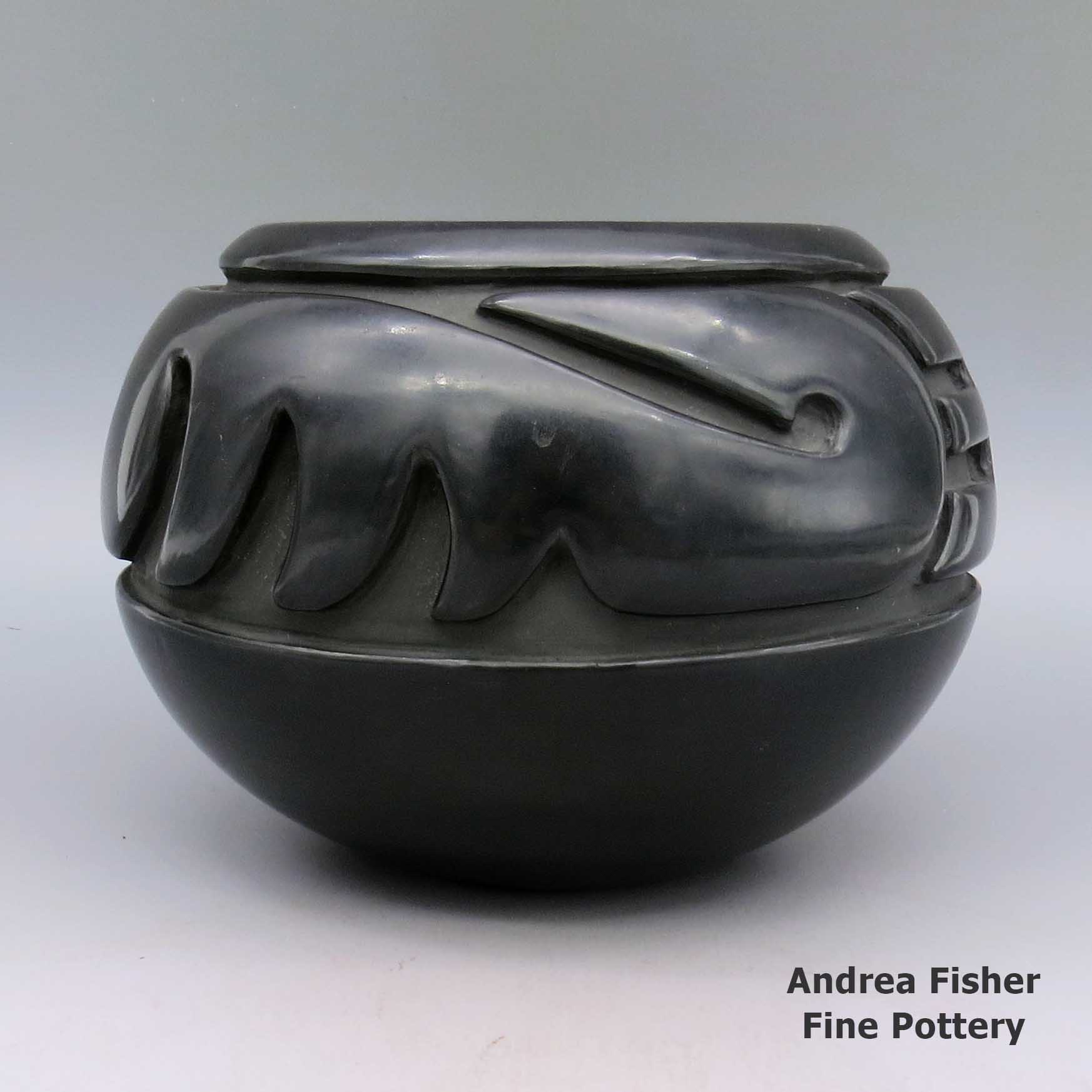

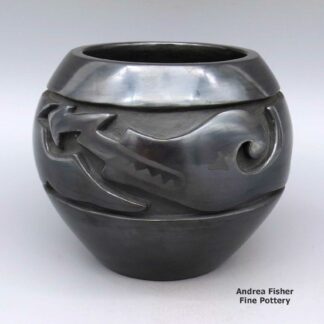

Margaret Tafoya, zzsc2h331, Bowl carved with avanyu design

$5,200.00

A black bowl carved around the shoulder with a stylized avanyu design

In stock

Brand

Tafoya, Margaret

"Excellence was the operative word. She raised the bar so high and required the next generation to rise to that level." - Nancy Youngblood speaking of her grandmother, Margaret Tafoya

"Excellence was the operative word. She raised the bar so high and required the next generation to rise to that level." - Nancy Youngblood speaking of her grandmother, Margaret TafoyaMaria Margarita "Margaret" Tafoya, given the Tewa name Gia-Khun-Povi, (meaning: Corn Blossom), unintentionally became the matriarch of Santa Clara Pueblo potters. Born in 1904 she learned the traditional art of pottery making from her mother, Sara Fina Tafoya. Her potting style was also influenced by her older sister Tomasita and by her paternal aunt, Santana Tafoya Gutierrez.

Born in Santa Clara Pueblo near Santa Fe, New Mexico, Margaret attended elementary school on the pueblo. When she wasn't in school she could usually be found making pottery. As a young girl she would accompany her parents, Sara Fina and Geronimo Tafoya, on clay-digging trips, taking picnics and traveling by horse and buggy. Later she attended Santa Fe Indian School as a boarding student from 1915 until 1918. That separated her from the clay for most of the year as she was only home in the summers. When her sister Tomasita died during the flu epidemic of 1918, Margaret returned home to stay with her mother.

Margaret had grown up under her mother's watchful eye, learning and slowly gaining more responsibility in regards to the clay. Finally, Margaret's work was as good as her mother's. That's when she married Alcario Tafoya: 1924.

Alcario was a painter and a wood carver. Margaret and Sarafina added his skills to their repertoire and together, they set the bar for Santa Clara pottery very high.

Margaret's name started to spread when Fred Harvey Detours started making trips by automobile to the pueblos from Santa Fe's La Fonda Hotel. Her reputation picked up further through continued participation in the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Fiestas de Santa Fe, the Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial and the New Mexico State Fair.

Margaret originally created traditional utilitarian red and black vessels. Following the ancient method of coil-building her pottery with clay taken only from the grounds of Santa Clara Pueblo, she continued her mother’s tradition of making exceptionally large pots with finely polished surfaces and simple carved designs. Her largest pieces were up to 24 inches tall and up to 21 inches in diameter. The clay for one of those took months to prepare, days to form and polish, then meticulous care through the firing process.

Margaret's "bear paw" motif and deeply carved pueblo symbols like the avanyu (the mythic Tewa water serpent) and kiva steps around the shoulder of her jars are now signature trademarks of Tafoya family pottery. Margaret also used her fingers to impress lines and bear paws into the clay. For deeper designs, she would draw them in pencil and Alcario would carve them. Alcario was an experienced wood carver but he wouldn't carve anything until a vessel had dried at least overnight.

Together, Margaret and Alcario raised thirteen children, many of whom carried on the family tradition of making pottery. Her commitment to quality, precision and esthetic simplicity in her pottery has been transferred to subsequent generations of her family. Her granddaughter Nancy Youngblood remembers, "Excellence was the operative word. She raised the bar so high and required the next generation to rise to that level."

Among the matriarchs of Pueblo pottery, Margaret Tafoya’s place is unique. She neither innovated a style like Maria Martinez, who originated black-on-black pottery at San Ildefonso Pueblo, nor revived an art form from prehistoric remains like Nampeyo of Hano at Hopi or Marie Z. Chino who perfected fine line pots at Acoma. She did, however, bind herself to the cultural traditions of Santa Clara Pueblo.

Margaret's curiosity led her to make a few pots in the Ohkay Owingeh Potsuwi'i style. She made a few pots using creamy clay coatings and various clay and vegetal slips. She even made a few pots in Roman and Greek forms. But she always came back to the forms and designs of her Tewa ancestors, taken from samples of Ancestral Puebloan pottery dating back as far as 500 CE.

Despite changes in styles and techniques over time, Margaret held firm to her faith in the clay. As a result of that commitment, she created some of the largest, simplest and most aesthetically pleasing pieces of Pueblo pottery made in the twentieth century.

By the 1960s Margaret’s pottery had become famous. She received the Best of Show Award in 1978 and 1979 at the Santa Fe Indian Market. In 1981, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded her a National Heritage Fellowship in recognition of her accomplishments. In 1984 she was given the New Mexico Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts. She was also recognized and received an award as a Master Traditional Artist in 1985.

Margaret’s first exhibition was held in 1974 at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She was honored with retrospectives in 1982 at the Denver Museum of Natural History and in 1983 at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe. In 1984, she was named Folk Artist of the Year by the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, DC and in 1985 and 1992 received Lifetime Achievement awards.

Margaret continued making pottery at Santa Clara until her death in 2001.

Margaret's first and only show held in a gallery was here at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery in 1998. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Margaret was famous and in her prime, there were very few galleries in Santa Fe, much less one that carried Native Art. Margaret's only sales venues were Indian Markets like the one held in Santa Fe for the last 100 years, or the inventory she sold from the brown shelves in her living room. By the time an American Indian art gallery existed, Margaret's pottery production had slowed down. The show at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery was a retrospective and celebration of her 94th birthday.

"Margaret's daughter, Shirley Cactus Flower Tafoya (or Berta as she was called by her family), was Margaret's main caretaker. Margaret's bedroom had two single beds and on the second one, two months before the show, Margaret carefully laid out the clothes she wanted to wear to the opening. Berta and I," said Andrea, "laughed because Margaret insisted that the clothes stay there and Berta had the job of dusting them for months.

"The day finally arrived. That morning Berta called me and said, 'Mom is not feeling well.' All I could think of was all of the advertising, all of the time to assemble the show material, the birthday cake and on and on and on and she would not be able to make an appearance. Two hours before the opening Berta called and said they would be there. I experienced the greatest relief of my life.

"It turns out she was not ill but so excited and extremely worried that no one would come, and WOW did they come! She was half-an-hour late for the reception and by the time she arrived, the Santa Fe Police and Fire Department had arrived, blocking the streets in the area in an effort to control traffic and the crowd of more than 2,000 people that were waiting for Margaret. This tiny little lady, on the arm of Berta, slowly parted the crowd to the whispers of 'there she is' and the cheers of others. It was like Moses parting the Red Sea. She was so happy, greeting everyone, posing for photographs and smiling through all the attention.

"I think there were many moments during that reception that she really enjoyed, including posing for a picture surrounded by her enormous family. She was surprised when Derek, who was 17 years old at the time, staggered under the weight of an enormous chocolate cake with ninety-four candles on it, presenting it to her while the crowd sang Happy Birthday! It is a wonder that the smoke alarm did not join in. It was an incredible evening. Margaret left the gallery hours later, happy and exhausted. Berta said she slept the entire next day. We will always remember Margaret as a lovely, charming lady who enjoyed hamming it up in front of a camera, who was extremely talented and who celebrated the pottery tradition of her heritage."

Some Exhibits that featured works by Margaret

- Beauty Speaks for Us. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. February 10, 2017 - March 31, 2017

- Over the Edge: Fred Harvey at the Grand Canyon and in the Great Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. Opened April 9, 2016

- Something Old, Something New, Nothing Borrowed: New Acquisitions from the Heard Museum Collection. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. April 2, 2011 - March 18, 2012

- Born of Fire: The Life and Pottery of Margaret Tafoya. Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 4, 2008 - January 9, 2009

- Choices and Change: American Indian Artists in the Southwest. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, Arizona. June 30, 2007 - September 29, 2007

- Home: Native People in the Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. May 22, 2005- Note: Heard Museum's ongoing, signature exhibition

- 75 Years at the Heard Museum. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. January 29, 2005 - 2006

- Breaking the Surface: Carved Pottery Techniques and Designs. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. October 2004 - October 2005

- The Collecting Passions of Dennis and Janis Lyon. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. May 1, 2004 - September 1, 2004

- Masterworks by Native Peoples of the Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. June 21, 2003 - June 20, 2005

- Every Picture Tells a Story. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. September 20, 2002 - September 1, 2005

- Hold Everything! Masterworks of Basketry and Pottery from the Heard Museum. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. November 1, 2001 - March 10, 2002

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. February 14, 1998 - May 17, 1998

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. The National Museum of Women in the Arts. Washington, DC. October 9, 1997 - January 11, 1998

- Recent Acquisitions. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. July 12, 1997 - January 11, 1998

- Timeless Impressions. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ November 12, 1994 - July 31, 1995

- The Galbraith Collection of Native American Art. Gallery of Indian Art. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. October 15, 1988 - May 7, 1989

- American Indian Art: The Collecting Experience. Elvehjem Museum of Art. University of Wisconsin/Madison. Madison, WI. May 7, 1988 - July 3, 1988

- Native People of the Southwest. Heard Museum. Phoenix, Arizona. 1985 - May 2003

- Margaret Tafoya: A Potter's Heritage and Her Legacy. Denver Museum of Natural History. Denver, CO. 1983 - January 22, 1984

- The Red and The Black: Santa Clara Pottery by Margaret Tafoya. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Santa Fe, NM. June 12, 1983 - September 16, 1983

- The Santa Fe Indian Market in Perspective. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Santa Fe, New Mexico. August 1979 - September 24, 1979

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

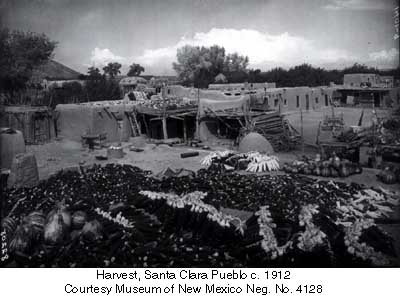

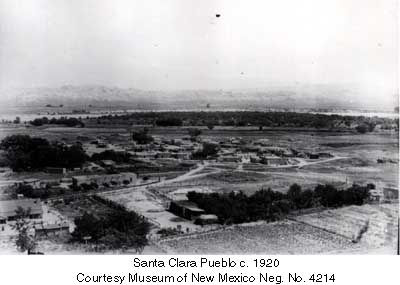

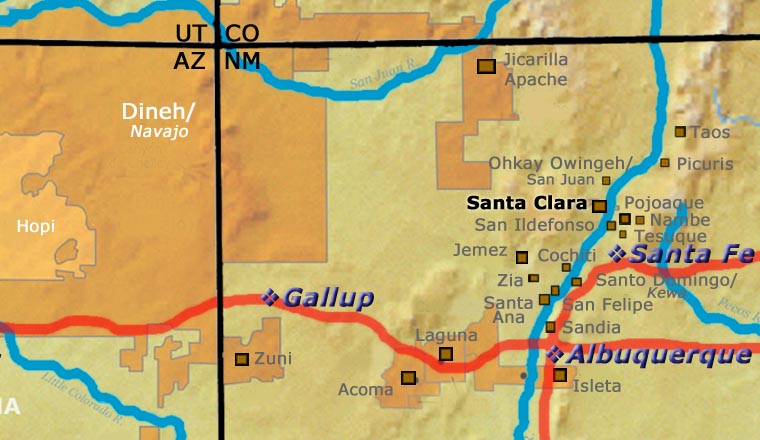

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

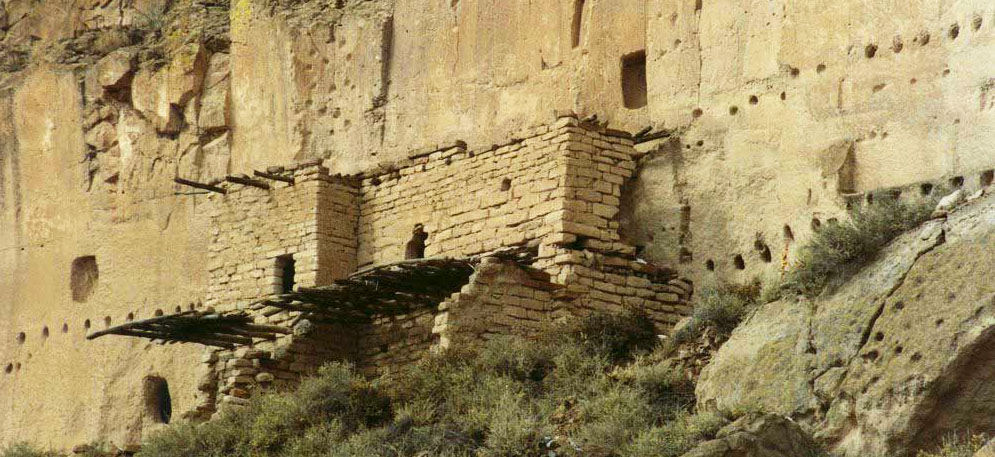

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About the Avanyu

The avanyu is a mythical water creature likened to the feathered and plumed serpents of Mesoamerica. The design is primarily part of the design palette of Tewa potters from the Tewa Basin, and even there it varies by pueblo and artist. Wherever the artist is, the avanyu design generally represents the spirit of water rushing through a village after a downpour. The avanyu is also seen as the Keeper of Springs and Guardian of Water. The image is a prayer for rain with the realization of what a downpour can do when it falls on the hard soil of the arid and semi-arid Southwestern deserts.

Artists from San Ildefonso Pueblo generally use an avanyu design with a three-plumed head while Santa Clara Pueblo potters generally use an avanyu with three feathers hanging off the head. The avanyu always has a forked tongue, signifying the lightning bolts that herald its arrival. Some have simplified the design to one feather or plume while others have stylized the design and almost made it cubic or Oriental in design and layout.

Hopi-Tewa potters generally use a somewhat similar Hopi version of a flying, feathered serpent named kwataka. The Zuni version is Kolowisi, although it has been determined that the power of Kolowisi is too much for anyone who is not of Zuni descent so depictions of it have gotten almost as rare as depictions of kwataka.

Sara Fina Tafoya Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Note: Sara Fina (Gutierrez) Tafoya was the older sister of Pasqualita Gutierrez. Pasqualita was born the same year Sara Fina married Geronimo Tafoya and their mother died shortly after. Sara Fina and Geronimo essentially raised Pasqualita.

- Sara Fina Tafoya (1863-1949) & Geronimo Tafoya

- Margaret Tafoya (1904-2001) & Alcario Tafoya (d. 1995)

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Barry Archuleta

- Bryon Archuleta

- Sheila Archuleta

- Jennie Trammel (1929-2010)

- Karen Trammel Beloris

- Virginia Ebelacker (1925-2001)

- James Ebelacker (1959-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Jamelyn Ebelacker

- Sarena Ebelacker

- Richard Ebelacker (1946-2010) & Yvonne Ortiz

- Jason Ebelacker

- Jerome Ebelacker & Dyan Esquibel

- Andrew Ebelacker

- Nicholas Ebelacker

- James Ebelacker (1959-) & Cynthia Ebelacker

- Lee Tafoya (1926-1996) & Betty Tafoya (Anglo)(1933-1988)

- Linda Tafoya (Oyenque)(Sanchez) (1962-)

- Antonio Jose Oyenque

- Jeremy Rio Oyenque

- Maria Theresa Oyenque

- Melvin Ray Tafoya (1957-)

- Phyllis Bustos Tafoya

- Linda Tafoya (Oyenque)(Sanchez) (1962-)

- Mela Youngblood (1931-1990) & Walt Youngblood

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Christopher Cutler

- Joseph Lugo

- Sergio Lugo

- Nathan Youngblood (1954-)

- Nancy Youngblood (1955-)

- Toni Roller (1935-) & Ted Roller

- Brandon Roller

- Cliff Roller (1961-)

- Deborah Morning Star Roller

- Jeff Roller (1963-)

- Jordan Roller (1987-)

- Ryan Roller

- Susan Roller Whittington (1955-)

- Charles Lewis (1972-)

- Tim Roller (1959-)

- William Roller

- LuAnn Tafoya (1938-) & Sostence Tapia

- Michele Tapia Browning (1960-)

- Ashley Browning

- Mindy Browning

- Daryl Duane Whitegeese (1964-) & Rosemary Hardy

- Samantha Whitegeese

- Tina Whitegeese

- Michele Tapia Browning (1960-)

- Shirley Cactus Blossom Tafoya (1947-)

- Meldon Wayne White Eagle Tafoya & Diana Tafoya

- Andrea Tafoya (1985-)

- Crystal Tafoya (1981-)

- Melissa Tafoya

- Mary Ester Archuleta (1942-2010)

- Christina Naranjo (1891-1980) & Jose Victor Naranjo (1895-1942)

- Mary Cain (1916-2010) & Willie Cain

- Billy Cain (1950-)

- Joy Cain (1947-)

- Linda Cain (1949-)

- Autumn Borts-Medlock (1967-)

- Tammy Garcia (1969-)

- Tina Diaz (1946-)

- Warren Cain (1951-)

- Douglas Tafoya

- Marjorie Tafoya Tanin

- Mary Louise Eckleberry (1921-2003)

- Darlene Eckleberry

- Victor (1958-) & Naomi Eckleberry (1961-)

- Teresita Naranjo (1919-1999)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Denise Chavarria (1959-)

- Joey Chavarria (1964-1987)

- Loretta Sunday Chavarria (Singer) (1963-)

- Stella Chavarria (1939-)

- Cecilia Naranjo & James Lee McLean

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Ira Atencio (1975-)

- Lawrence Thunder Atencio

- Judy Tafoya (1962-) & Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Cecilia Fawn Tafoya (1986-)

- Chelsea Tafoya

- Eli Tafoya (1991-)

- Josetta Tafoya (1993-)

- Lincoln A. Tafoya (1989-)

- Linette Tafoya (1989-)

- Sarah Ayla Tafoya (1987-)

- Sharon Naranjo Garcia (1951-) & Lawrence Atencio (San Juan)

- Mida Tafoya (1931-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Kimberly Garcia (1978-)

- Cookie Kathleen Tafoya (1963-)

- Robert Maurice Moe Tafoya

- Donna Tafoya (1952-)

- Mike Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis Tafoya (1955-) & Matthew Tafoya (1953-)

- Lorraine Tafoya

- Matthew Tafoya Jr.

- Sabina Tafoya

- Sherry Tafoya (1956-)

- Phyllis & Marlin Hemlock (Seneca)

- Lincoln Tafoya (1954-)

- Ethel Vigil (1950-2021)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo & Gracie Naranjo (Dineh)

- Edward Mickey Naranjo Jr.

- Teresa Naranjo

- Tracy Naranjo

- Mary Cain (1916-2010) & Willie Cain

- Camilio Tafoya (1902-1995) & Agapita Silva (1904-1959)

- Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012) & Joe Tafoya

- Kelli Little Kachina (1967-2014)

- Myra Little Snow (1962-)

- Forrest Red Cloud Tafoya

- Shawn Tafoya (1968-)

- Joseph Lonewolf (1932-2014) & Katheryn Lonewolf

- Greg Lonewolf (1952-)

- Rosemary Apple Blossom Lonewolf (1954-) & Paul Speckled Rock (1952-2017)

- Adam Speckled Rock

- Susan Romero & Mike Romero

- Grace Medicine Flower (1938-)

- Lucy Year Flower (1935-2012) & Joe Tafoya

- Dolorita Padilla (1897-1960) & Alberto Padilla (1898-)

- Manuel Tafoya (c. 1895-1958) (Painted pots for Sara Fina and for Margaret)

- Tomasita Tafoya Naranjo (1884-1918) & Agapito Naranjo (1880-1958)

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

- Adele Naranjo

- Howard & Linda Naranjo

- Charlotte Naranjo Suina

- Roberta Naranjo

- Nicolasa Naranjo (c.1910-) & Jose G. Tafoya

- Juan Isidro Tafoya & Valerie Sisneros Isidro (Ohkay Owingeh)