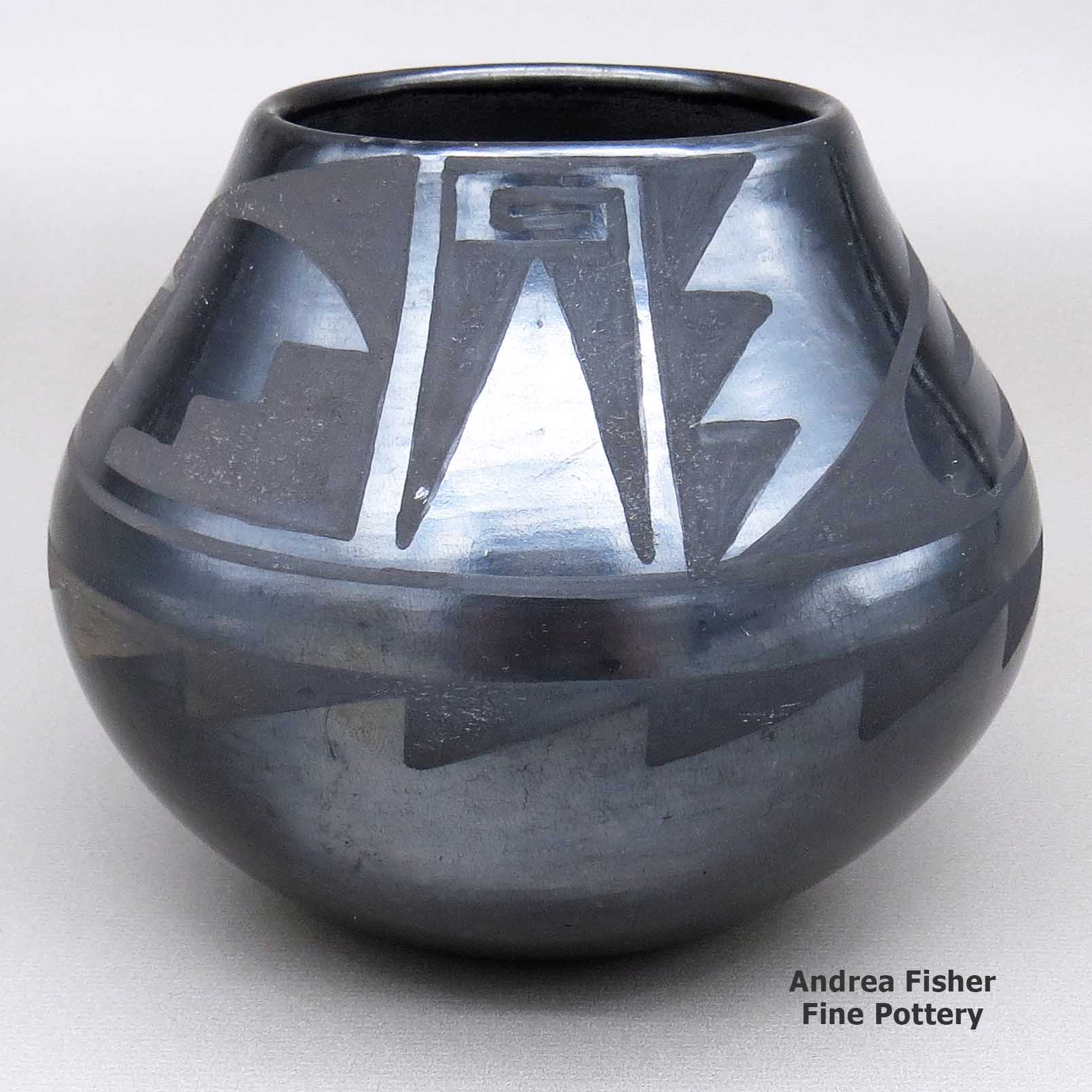

| Dimensions | 5.25 × 5.25 × 4.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has some wear around rim |

| Date Born | 1956 |

| Signature | Maria Santana |

Maria Martinez, zzsi3c130, Jar with geometric design

$3,800.00

A black-on-black jar decorated with a four-panel bat wing, lightning bolt and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Martinez, Maria

Undoubtedly the world's most famous Native American potter, Maria Montoya Martinez was born in the Tewa pueblo of San Ildefonso around 1887. Back in those days records were maintained by the church and as far as they were concerned, no one was born until they were baptised. Maria's baptism certificate says 1887, she herself thought she might have been 7 by then.

Undoubtedly the world's most famous Native American potter, Maria Montoya Martinez was born in the Tewa pueblo of San Ildefonso around 1887. Back in those days records were maintained by the church and as far as they were concerned, no one was born until they were baptised. Maria's baptism certificate says 1887, she herself thought she might have been 7 by then.As she grew up, Maria observed her aunt, Nicolasa, making pottery. She was very interested and learned the basics of the traditional art of pottery making through watching and working with her.

In the early years of her career, Maria produced the traditional polychrome pottery of her village, generally black and terra cotta decorations painted on a background of white or tan. She shaped her pots the age-old way, by carefully hand-coiling and pinching the clay, then smoothing the inner and outer surfaces with gourd scrapers. However, Maria wasn't happy with her own painting skills so she went to others to have any decorations added.

Early on her pots were recognized as the thinnest and most beautifully shaped pots being made at San Ildefonso. She had no trouble finding painters to decorate her pieces. Then the man who became her husband, Julian Martinez, an accomplished painter of hides, paper and walls, began decorating more and more pots for her. Then he worked with her in the firing of them.

Maria and Julian were married in 1904. From the beginning of their relationship they were traveling to demonstrate their craft at various fairs and expositions. They spent their honeymoon in 1904 demonstrating traditional San Ildefonso pottery making at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition at the St. Louis Worlds Fair.

They demonstrated their crafts again at the Panama California Expo in San Diego in 1915, the Chicago Worlds Fair in 1934, and the Golden Gate International Expo in 1939.

Native American craft fairs provided other marketing opportunities, and when she began signing her work, Maria both heightened her visibility and commanded higher prices. In 1954, she was awarded the Craftsmanship Medal, the highest honor awarded by the American Institute of Architects.

Contrary to legend implying that Maria "discovered" the black pottery process, Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett, Professor of Archaeology at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and Director of the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe, found sherds of prehistoric black pottery while excavating in the ruins of Tsankawi (a non-contiguous part of Bandelier National Monument) in 1908. Tsankawi was an ancestral home of the San Ildefonso people.

To preserve and showcase that ancient product, Hewett went to San Ildefonso Pueblo and sought a skilled pueblo potter who could re-create that ancient style for him. Everyone he asked referred him to Maria. Together they worked out a deal and he pre-ordered (and paid for up front) a series of black pots from her.

When he returned, two years later, she had some black pots to show him. She wasn't very happy with them but Hewett and his students were. They bought everything she had, even the ones she'd hidden under her bed. Then they commissioned more and paid for them, again in full and up front.

That led to several years of experimentation, until Maria and Julian were satisfied with their results in not just recreating that style of blackware but in going a step further. Their method required smothering the fire with manure during the firing process, effectively creating an "oxygen-reduction process" that turned the would-be-red pots black.

Julian worked out the other half of the "black-on-black" process when he began painting his designs "in the negative," using a matte black paint on the polished pot surface to create his decorations. Once fired, that demonstrated the technique that has become so famous today.

According to Susan Peterson in The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez, the six distinct steps involved in the creation of blackware pottery include, "finding and collecting the clay, forming a pot, scraping and sanding the pot to remove surface irregularities, applying the iron-bearing slip and burnishing it to a high sheen with a smooth stone, decorating the pot with another slip, and firing the pot."

Julian faced a challenge in attempting to decorate Maria's pots. The process he finally settled on involved polishing the background first and then applying the matte slip to outline the decoration and fill in the background. In 1918, Julian finished their first decorated blackware pot with a matte black background and a polished avanyu (horned water serpent) design. Many of Julian's decorations were patterns adopted from ancient vessels of the pueblos. Some of the patterns consisted of feathers, birds, road runner tracks, deer tracks, rain, clouds, mountains, lightning bolts and kiva steps.

As her pots attracted more and more attention for their unique beauty, Maria began to slowly raise her prices. With the demand for her pots growing, she realized that her work could enrich the lives of the people of her pueblo, artistically and economically.

After the Spanish flu pandemic passed through in 1918-1919, the pueblo was reduced to less than 90 members. Maria's efforts back then virtually saved her people. In the ages-old puebloan manner, she generously shared her techniques with others. Maria became the matriarch of a "craft lineage" that continues today. In a career that spanned seven decades, her pottery brought honors and acclaim, revitalizing the art and the economy of San Ildefonso Pueblo.

Even though Julian decorated the pots, Maria claimed all the work in the early years because pottery was still considered a woman's job in the pueblo. Maria started to sign her pottery with "Marie" in 1922. She signed "Marie" because Kenneth Chapman, Director of the Museum of New Mexico, had convinced her "Marie" was a name more familiar to the Anglo buying public than "Maria" and should command higher prices.

They left Julian's signature off their pieces to respect the norms of Pueblo culture until 1926. Then Maria decided that since Julian was doing half the work, as the painter he should get half the credit. After that, "Marie + Julian" was the official signature on their pottery until Julian's death in 1943.

Maria's family began helping more with the pottery business after Julian died. From 1943 to 1956 Maria's son Adam took over collecting clay and materials for firing while his wife Santana took over painting decorations. "Marie + Santana" was the signature on their pots. These years were also Maria's most prolific years.

Maria's younger son, Popovi Da, spent four years in the US Navy after World War II. In 1950 he returned to San Ildefonso and, at the urging of Maria, began learning to paint with Santana. In 1956 he agreed to do Maria's painting for her. That's when Santana went back to her home and began working with Adam under their name. The signature on Maria's pots became "Maria/Popovi", until 1971 when Popovi passed on. Maria didn't make another piece after his death.

Popovi had also often been busy with tribal politics during those years and, at times, couldn't keep up with painting Maria's pots. As Maria almost never painted a pot, those pots are plain and signed "Maria Poveka" (Poveka being her Tewa name, meaning: "pond lily").

Today, values on Maria's work vary based on the signature on the bottom, those with "Maria + Popovi" being among the most valued of all Pueblo pottery. After making pots for almost 80 years, Maria passed on in 1980.

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

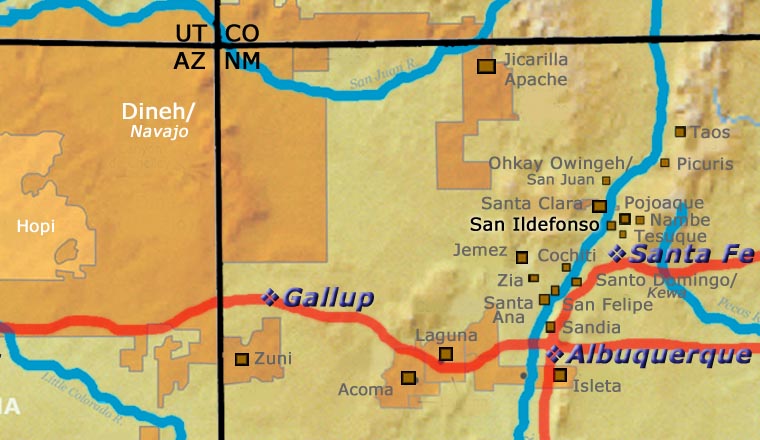

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

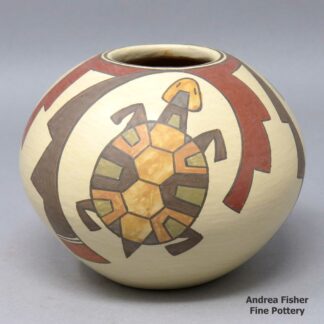

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

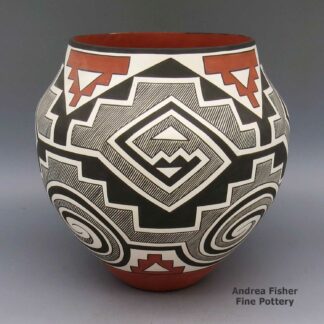

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.

Maria Martinez Family Tree - San Ildefonso Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Reyes Peña (d. 1909) & Tomas Montoya (d. 1914)

- Maria Montoya Martinez (1887-1980) & Julian Martinez (1884-1943)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) & Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Anita Martinez (d. 1992) & Pino Martinez

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Aaron Gonzales (1971-)

- Brandon Gonzales (1983-)

- Cavan Gonzales (1970-)

- Derek Gonzales (1986-)

- Kathy Wan Povi Sanchez (1950-) & Gilbert Sanchez (San Juan)

- Corrine Sanchez

- Gilbert Abel Sanchez

- Liana Sanchez

- Wayland Sanchez

- Evelyn Than-Povi Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Berlinda Garcia

- Myra Garcia

- Peter Pino

- Barbara Tahn-Moo-Whe Gonzales (1947-) & Robert Gonzales

- Viola Martinez/Sunset Cruz & Johnnie Cruz Sr.

- Beverly Martinez (1960-1987)

- Marvin Martinez (1964-) & Frances Martinez

- Johnnie Cruz Jr. (1975-)

- George Martinez (1943-) & Pauline Martinez (Santa Clara)(1950-)

- Popovi Da (1921-1971) & Anita Da

- Tony Da (1940-2008)

- Adam Martinez (1903-2000) & Santana Roybal Martinez (1909-2002)

- Desideria Montoya (1889-1982)

- Maximiliana Montoya (1885-1955) & Cresencio Martinez (1879-1918)

- Juanita Vigil (1898-1933) & Romando Vigil (1902-1978)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Erik Fender (1970-)

- Gloria Maxey (d. 1999)

- Angelina Maxey (1970-)

- Jessie Maxey (1972-)

- Martha Appleleaf (1950-)

- Carmelita Vigil Dunlap (1925-1999) & Carlos Dunlap (d. 1971)

- Carlos Sunrise Dunlap (1958-1981)

- Cynthia Star Flower Dunlap (1959-)

- Jeannie Mountain Flower Dunlap (1953-)

- Linda Dunlap (1955-)

- Carmelita Vigil (1925-1999) & Nicholas Cata

- Maria Montoya Martinez (1887-1980) & Julian Martinez (1884-1943)